Where on earth do you begin if all the world’s a stage? When not sifting through the entrails of dynastic English history or sunning themselves in Italy, the plays of Shakespeare really do put a girdle round the known globe. They send postcards from the exotic neverlands of Illyria and Bohemia, wander deep into Asia, set foot as far south as Africa, trespass up to the chilly north of Scandinavia and Scotland, and even make reference to Muscovy. And of course there are the Anthropophagi (wherever they're from). To map this world is something only the British Museum, that most capacious cabinet of curiosities, could attempt.

And the curators have taken Jacques at his word: Staging the World suggests a sort of seven stages of Shakespeare. In this unmissable contribution to the World Shakespeare Festival, the story begins in Elizabethan London and fetches up on Prospero’s mysterious island. It passes along the way through the pastoral retreat of the forest, the twin realms of classical Rome and regal England, before putting in at Venice’s busy migrants' hub and summoning the mystical Britain of the Jacobean imagination.

The task of this exhibition is to invoke all this in solid form, in bits of old timber and bone, coins and parchment, decks of cards and yards of tapestry, trinkets, baubles, brooches, vases, platform slippers known as chopines, plus a great deal of military hardware. Above all there are books, not least the holiest writ of them all, an edition of the First Folio open on the page in which the Bard favours posterity with an enigmatic, asymmetrical glance (if that’s actually him, that is). Well, it must be someone whose hand we read in the only surviving example of verse written in Shakespeare’s hand. This was his contribution to a group effort on the subject of Thomas More, whom we hear exhorting the London mob to be tolerant to refugees sheltering from the religious persecution that characerises the age: “the wretched strangers/ Their babies on their backs with their poor luggage/ Plodding to th’ports and coasts for transportation”. So it’s not the Bard’s most seductive iambic pentameter, but in these crosshatched scribbles the man’s humanity is very much in the room.

The task of this exhibition is to invoke all this in solid form, in bits of old timber and bone, coins and parchment, decks of cards and yards of tapestry, trinkets, baubles, brooches, vases, platform slippers known as chopines, plus a great deal of military hardware. Above all there are books, not least the holiest writ of them all, an edition of the First Folio open on the page in which the Bard favours posterity with an enigmatic, asymmetrical glance (if that’s actually him, that is). Well, it must be someone whose hand we read in the only surviving example of verse written in Shakespeare’s hand. This was his contribution to a group effort on the subject of Thomas More, whom we hear exhorting the London mob to be tolerant to refugees sheltering from the religious persecution that characerises the age: “the wretched strangers/ Their babies on their backs with their poor luggage/ Plodding to th’ports and coasts for transportation”. So it’s not the Bard’s most seductive iambic pentameter, but in these crosshatched scribbles the man’s humanity is very much in the room.

London is naturally the most assertive presence here. You can all but join, for instance, the groundlings in the city’s many theatres. Retrieved from the rubble of the Rose are dice, a pipe, a beautiful Italian fork and a bit of oak baluster. More eye-catching is the skull of a bear dug up from under the site of the Globe (pictured above. Copyright of Dulwich College). It's no surprise to find bears in the home of play-goers. In a splendid 1649 London panorama by Wenceslaus Holler, the Globe in Southwark is cheek by jowl with a building labelled “beere bayting”. The exhibition, incidentally, houses quite a menagerie. There are falcons, hounds and deer in a tapestry depicting rural pursuits (which also includes womanising), butterflies in Jacques Le Moyne’s 1585 album of pretty floral watercolours, a red deer’s antlers such as might have been worn by Falstaff, and a huge wooden globe from Venice in which the constellations are represented by lions, serpents and, of course, a great bear.

London is naturally the most assertive presence here. You can all but join, for instance, the groundlings in the city’s many theatres. Retrieved from the rubble of the Rose are dice, a pipe, a beautiful Italian fork and a bit of oak baluster. More eye-catching is the skull of a bear dug up from under the site of the Globe (pictured above. Copyright of Dulwich College). It's no surprise to find bears in the home of play-goers. In a splendid 1649 London panorama by Wenceslaus Holler, the Globe in Southwark is cheek by jowl with a building labelled “beere bayting”. The exhibition, incidentally, houses quite a menagerie. There are falcons, hounds and deer in a tapestry depicting rural pursuits (which also includes womanising), butterflies in Jacques Le Moyne’s 1585 album of pretty floral watercolours, a red deer’s antlers such as might have been worn by Falstaff, and a huge wooden globe from Venice in which the constellations are represented by lions, serpents and, of course, a great bear.

As well as books, the dust is blown off many paintings which in another context would not necessarily catch the eye: Richard III with symbolically broken sword (see gallery overleaf) or Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud ben Mohammed Anoun (pictured above left), the ambassador to England from the King of Barbary, a Moroccan whose glowering eyes evoke irresistible thoughts of the Moor. A lovely before-and-after diptych by John Gipkyn (1616) featuring the Old St Paul’s suggests the apotheosis of the Church Triumphant. In one, crows circle grimly above its collapsed spire, while in the other winged angels trumpet its fresh restoration. (It wouldn’t be till Wren that fantasy became reality.)

The curators can be forgiven the odd fanciful claim of their own. A mouldy old saddle and shield are “associated” with the funeral of Henry V much as a lantern (pictured right) is said to have been in the possession of Guy Fawkes, perhaps on the fateful night he was caught red-handed, condemning his fellow plotters to a gruesome execution depicted here in a 1606 print. But other objects speak unequivocally: metal restraints for witches, a silver reliquary containing the eye of a Jesuit, a seal-die establishing Raleigh as governor of Virginia.

The curators can be forgiven the odd fanciful claim of their own. A mouldy old saddle and shield are “associated” with the funeral of Henry V much as a lantern (pictured right) is said to have been in the possession of Guy Fawkes, perhaps on the fateful night he was caught red-handed, condemning his fellow plotters to a gruesome execution depicted here in a 1606 print. But other objects speak unequivocally: metal restraints for witches, a silver reliquary containing the eye of a Jesuit, a seal-die establishing Raleigh as governor of Virginia.

The Tudors’ and Stuarts’ eagerness to throw their weight about is found in sundry maps of England’s dominions. In the corner of one, the map-maker Laurence Nowell portrays himself hurrying to finish as a dog impatiently barks at him while Sir William Cecil waits in the opposite corner with an hourglass. The Spaniard-baiting Francis Drake looks menacing as cannonballs crowd at his feet. There are hopeful designs from 1604 for a prototype Union Jack, and a vast genealogical cloth King James commissioned to establish Brutus, the first Briton, as his ancestor. The Scottish king was grateful to his genealogist Thomas Lyte, gifting him a jewelled miniature of himself by way of acknowlegement (see gallery below).

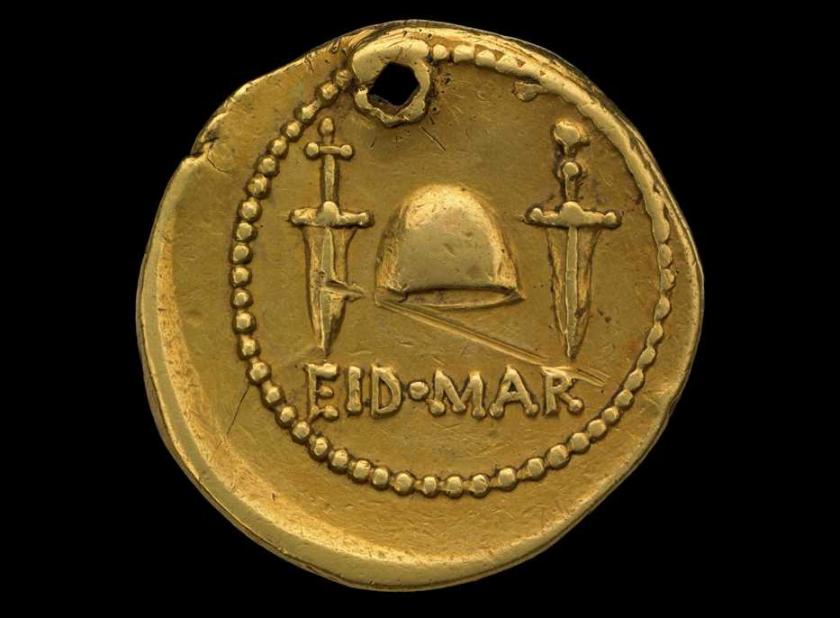

And talking of (a different) Brutus, the proximity of the classical world is powerfully contained in one tiny coin, minted by Brutus to commemorate the assassination of Julius Caesar. On the back are two daggers and a freedman’s cap (see main image). In one of several video installations featuring actors, Paterson Joseph (Brutus in the RSC’s African production of the play) is seen brandishing the self-same coin.

If contemporary anxiety about gunpowder, treason and plot was refracted through tales of the ancients, antiquity had other uses. The Elizabethans found an uplifting equivalence between their Virgin Queen and Egypt’s more sexually active pharaoh. A set of cards used as a teaching aid for the young Louis XIV lionised the heroines Cleopatra and Elizabeth I. (The notes omit to highlight the presence in the same deck of one “Marie Stuard”.) It may be thought germane that Harriet Walter, seen here as Cleopatra, has also played Schiller's Good Queen Bess.

Staging the World turns into an voluptuous feast as we move to Venice, the original città aperta where a 17th-century form of multiculturalism held sway. The city of Othello and Shylock offers beautiful Murano glass and a ravishing bust of a black African by Nicolas Cordier (actually made in Rome). It's enough to make you want to emigrate. At the time, some Englishmen couldn't resist. In the 1590s friendship album of one such adventurous traveller, Venice is represented by the image of a courtesan in a dress; a flap can be lifted to reveal her sumptuous red drawers. And then there was Jewish Venice, shown in a scroll of the Book of Esther in Hebrew and a collection of ducats with a balance and coin weights. A curatorial wag has counted out 30 pieces.

Staging the World turns into an voluptuous feast as we move to Venice, the original città aperta where a 17th-century form of multiculturalism held sway. The city of Othello and Shylock offers beautiful Murano glass and a ravishing bust of a black African by Nicolas Cordier (actually made in Rome). It's enough to make you want to emigrate. At the time, some Englishmen couldn't resist. In the 1590s friendship album of one such adventurous traveller, Venice is represented by the image of a courtesan in a dress; a flap can be lifted to reveal her sumptuous red drawers. And then there was Jewish Venice, shown in a scroll of the Book of Esther in Hebrew and a collection of ducats with a balance and coin weights. A curatorial wag has counted out 30 pieces.

We end up in Prospero’s otherwhere, which may be taken to symbolise the undiscovered countries that in succeeding centuries would adopt Shakespeare as their own. The playwright's legacy can be measured in the final and perhaps most powerful exhibit of all. A complete works smuggled onto Robben Island as a Bible was passed furtively around by the prisoners, each of whom was invited to mark their favourite passage (pictured above left. Collection of Sonny Venkatrathnam, Durban). The page is open on Julius Caesar and the following lines are marked:

Cowards die many times before their deaths;

The valiant never taste of death but once.

Of all the wonders that I yet have heard,

It seems to me most strange that men should fear;

Seeing that death, a necessary end,

Will come when it will come.

The date is 16.12.77. The signature belongs to "NRD Mandela". Not all the men and women on Shakespeare’s stage are merely players.

Overleaf: see a gallery of exhibits from Staging the World

Click on the thumbnails to enlarge

Add comment