Charismatic, full of vital elan to the end, inconsistent, fitfully creative, a casually anti-semitic Conservative Catholic married to two of the greatest Jewish artists, Alma Mahler/Gropius/Werfel née Schindler can never be subject to a boring biography. A child of her fin de siècle time, torn between the need to be free and the will to inspire great figures, she was all too often gauged by the men who loved and tried to dominate her. Cate Haste gives us their verdicts, but the picture drawn from Alma's diaries and autobiographies only confirms the general portrait.

There's little new here, despite Haste's claims of "deep delving" (somewhat undermined by immediate acknowledgment of help from researchers and translators - inevitably disdained by those of us compelled to be lone-wolf biographers). It's good to read around the years with Gustav Mahler, who all too typically told his new wife that there wasn't room for two composers in the marriage but in his desperation to keep Alma from her new love Walter Gropius finally gave encouragement to her song-writing just before he died.

Gustav Klimt, her first great love, told her she was "spoilt by too much attention, conceited and superficial". In him, Zemlinsky and Mahler she obviously sought a replacement for the artist father she revered, who died when she was 13 years old (one revelation here, drawn from Marie Bonaparte's unpublished diary manuscript as reproduced in Stuart Feder's Gustav Mahler: A Year in Crisis, tells us more about Mahler's meeting with Freud and the great psychonalyst - rather than "psychotherapist," as Haste puts it - enlightening him about his mother-fixation).

After Mahler's death, Alma went for younger men: the terrifying and sado-masochistic Oscar Kokoschka, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and the most popular Austrian-based author of his time, Franz Werfel, with whom she stayed as her charms faded and for whom she made practical moves of self-sacrifice, showing remarkable fortitude in their escape from the Nazis through France - including some time in Lourdes, which gave Werfel inspiration for The Song of Bernadette - to Spain, Portugal and on to America.

After Mahler's death, Alma went for younger men: the terrifying and sado-masochistic Oscar Kokoschka, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and the most popular Austrian-based author of his time, Franz Werfel, with whom she stayed as her charms faded and for whom she made practical moves of self-sacrifice, showing remarkable fortitude in their escape from the Nazis through France - including some time in Lourdes, which gave Werfel inspiration for The Song of Bernadette - to Spain, Portugal and on to America.

The language of Alma's diaries and her exchanges with many of her lovers show a gushing romantic delusion that never gave way to real self-knowledge. She is refreshingly, occasionally embarrassingly, frank about her sexual experiences, dangerously ignorant of the political sphere - which led to huge clashes with the politically engaged left-winger Werfel - and sometimes risibly egotistical about it (of the First World War: "I sometimes imagine that I was the one who ignited this whole world conflagration in order to experience some kind of development or enrichment - even if it be only death"). She later repented her admiration of "genius" Hitler and tried to airbrush it out of her reminiscences and collection of letters, but for all that she never estranged most of the members of the Jewish circle in which she mixed, both in Vienna and Los Angeles.

Something of her flightiness is captured in Tom Lehrer's masterful song "Alma":

Perhaps the most devastating verdict on Alma's ability to move on came from her daughter by Gropius, Manon - the same "angel" to whom Berg dedicated his Violin Concerto - as unflinchingly recorded by the mother in her diary: " 'Let me die in peace...You'll get over it, the way you get over everything', and as if to correct herself, 'like everyone gets over everything' ". It can't have been easy: Manon was the third child she lost. And who are we to judge?

As for Alma's work as a composer, Haste offers no guidance on the surviving songs - much was destroyed in the Second World War - until the end, where she concludes rather weakly with "her own music is her lasting, and living, legacy". In fact the songs are good, but inevitably not on the level of her first husband's work (what is?) They have found their place in performance, and their level: worth hearing, but hardly genius. Had Alma been a born creator, she would have persisted with her work. Clearly she was an excellent pianist, even if it's unlikely that, as Haste claims, she played entire Wagner operas from memory - only of the composer Enescu, a phenomenal intelligence, can that be true. In all else she was, as one observer commented, a generalist with a vague grasp of facts.

The narrative is racy, with clear fill-ins on the historical background, but a few German names are misspelt (about a dozen), suggesting a lack of engagement with the language (and Haste uses mostly secondary sources). A good popular biography, though, and beautifully presented, as usual, by Bloomsbury Publishing.

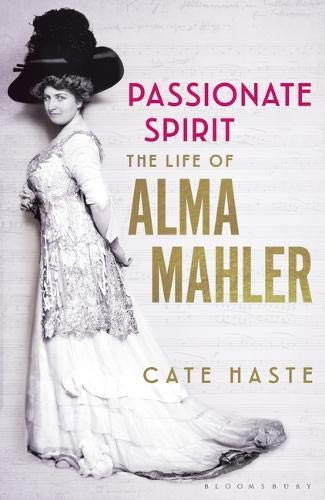

- Passionate Spirit - The Life of Alma Mahler by Kate Haste (Bloomsbury Publishing, £26)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment