This is a love story and a ghost story. The year is 1934 and the Held family have moved from the countryside to an elegant house on Katalin Street in Budapest. Their new neighbours are the Major (with whom Mr Held fought in the Great War) and his mistress Mrs Temes, upright headteacher Mr Elekes and his slovenly and unconventional wife Mrs Elekes.

Almost as soon as Henriette, the diminutive daughter of the Helds, begins to explore the house, she is ambushed by her mother at the threshold of her new bedroom and introduced – in the assured, declaratory manner of adults – to the Elekes’ daughters with the proclamation, “These are your new friends!” She’s not wrong. There is Irén who is dark, and serious and gracious, and blonde Blanka “who was in constant movement, wriggling like an eel”. Later, Bálint, the fourth of the young ones and the son of the Major, appears. Characteristically, one of the first things he does is to simultaneously include her in their games and insult her: “Henriette will play with us. Don’t you have another name? Henriette is a terrible name.”

Nevertheless it’s a warm welcome to a cast of characters who will come to mean much to Henriette, even once she is dead. Her death occurs a decade later, during the Nazi occupation of Budapest as Jewish people are being rounded up, and it comes more of a surprise to her that she is suddenly, actually dead than that she continues to exist in a somewhat liminal way. From her youthful vantage point she checks on her friends as they age, though as their lives unravel and disappointment and despair set in, she tends to retreat to the comfort of the idealised version of Katalin Street she has constructed in the afterlife – one of Szabó’s uncannier novelistic inventions. There, all events are predictable, each person is the best and utmost they ever were, and the future (such as it was) shimmers with possibility.

Szabó doesn’t make clear whether this ghostly world is a kind of internment camp for the dead – a passing point like limbo – or a completely new plane of existence. It could be particular to the cruelties of the second world war or it could encompass everyone who has ever lived. What is plain is that Henriette reappears at crucial points in the lives of those she loves and that her continued existence is both a metaphor for the way memory works as well as an actual fact. So when in 1952 Bálint faces a hospital disciplinary panel charged with taking bribes, the words of a play the four children acted intrude on his thoughts – “I shall attack you, I shall vanquish you, I shall chop your arms and legs to pieces,” – not just because the situation is appropriate and Blanka is present, but because Henriette is too.

Szabó doesn’t make clear whether this ghostly world is a kind of internment camp for the dead – a passing point like limbo – or a completely new plane of existence. It could be particular to the cruelties of the second world war or it could encompass everyone who has ever lived. What is plain is that Henriette reappears at crucial points in the lives of those she loves and that her continued existence is both a metaphor for the way memory works as well as an actual fact. So when in 1952 Bálint faces a hospital disciplinary panel charged with taking bribes, the words of a play the four children acted intrude on his thoughts – “I shall attack you, I shall vanquish you, I shall chop your arms and legs to pieces,” – not just because the situation is appropriate and Blanka is present, but because Henriette is too.

From the height of war through to Stalinism, the 1956 Hungarian uprising and its 1968 reprise, Szabó moves us across the decades. But while their lives are tossed by vast storms of political upheaval, these events seem less real than complications to the tangled expressions of love between Irén, Blanka, Bálint and Henriette. We’re moved across perspectives too: Irén’s contributions are told in the first person, Bálint’s, Blanka’s and Henriette’s in the third. The weighting is uneven and purposefully so – translator Len Rix (who won the 2018 PEN translation Prize for Katalin Street as well as translating Szabó's The Door) does deft work at never quite letting us into Blanka’s thoughts in the way we are Henriette’s, for example – but we are nevertheless party to complicated arrangements of allegiance, betrayal and misapprehension.

Love and pain, life and death overlay each other in peacetime as in war. It’s mundane details that lend animation, but in the end these are tired and stymied people whose own lives are out of their control. It's worth remembering that between 1949 and 1958, Szabó's works were banned under the communist dictatorship of Matyas Rakosi, a rule which crushed many lives. Memories of Katalin Street feel close because each lives under “the tyranny of somewhere else,” the sense that they are alive and flourishing elsewhere while where they actually are is a matter of going through the motions. It’s not just Henriette whose spirit haunts the book. Each is a ghost in their own life.

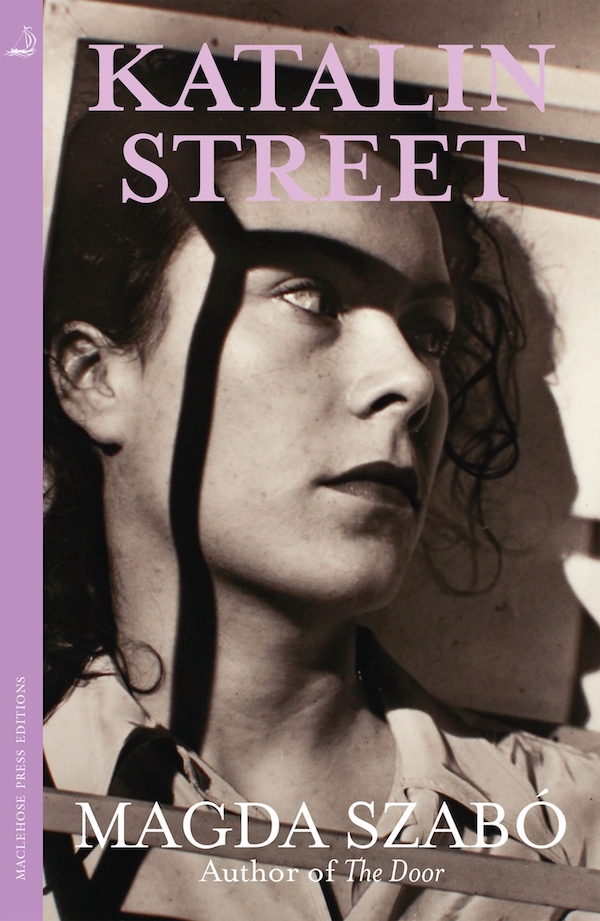

- Katalin Street by Magda Szabó trans. Len Rix (Quercus, £12.99 paperback)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment