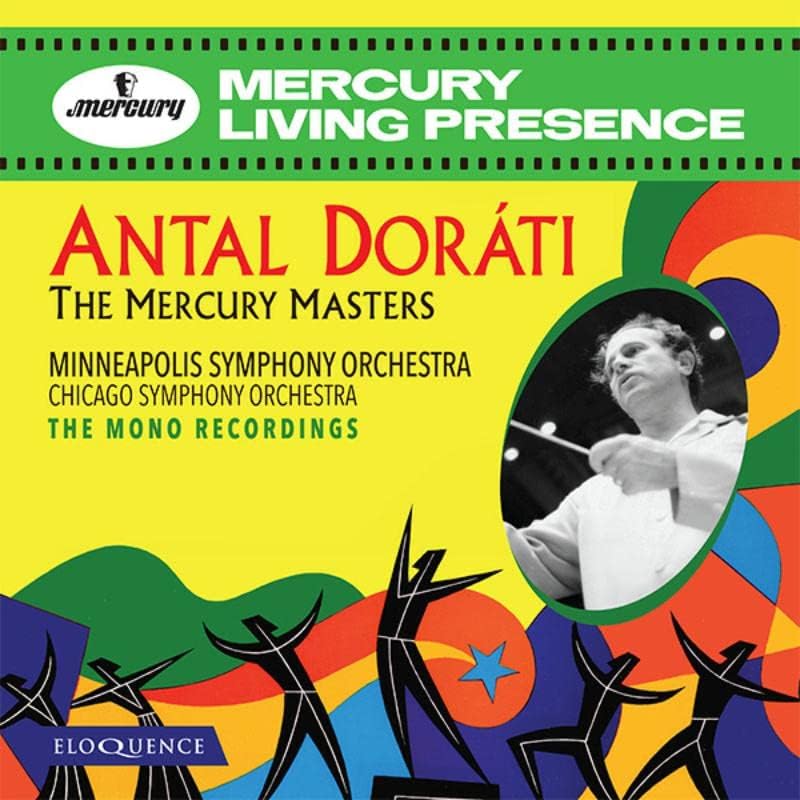

Antal Doráti: The Mercury Masters – The Mono Recordings (Decca Eloquence)

Antal Doráti: The Mercury Masters – The Mono Recordings (Decca Eloquence)

The great Hungarian conductor Antal Doráti (1906-1988) enjoyed a long and prolific recording career, stretching from the mid-1940s to the early 1980s. This beautifully produced 30-CD package is one of two dedicated to Doráti’s 11-year stint in charge of the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra (now known as the Minnesota Orchestra). Doráti’s predecessor was the charismatic, erratic Dimitri Mitropoulos. His penchant for new and challenging music wasn’t to all tastes, and in 1949 Doráti took charge of an ensemble whose players needed stability and consistency. In his words, “it was a great change for the orchestra to have, instead of an ascetic figure shrouded in cloudy mystery, a young man who wished… to be just another member of the orchestra.” Doráti believed in thorough, painstaking preparation and significantly expanded the ensemble’s repertoire during his tenure. He saw himself as “a specialist in non-specialism,”, able to move from Haydn to Stravinsky, from Beethoven to Bartok with ease. Here we get the mono recordings which Doráti and the Minneapolis players taped for the Mercury label between 1951 and 1954, and an equally absorbing companion volume collects the stereo follow-ups. Audiophiles have a soft spot for the distinctive Mercury sound, engineer C. Robert Fine achieving miraculous results with a single microphone suspended high above the stage of the University of Minnesota’s cavernous Northrop Auditorium.

That these recordings are 70 years old is never an issue, and the sound is consistently clear, bright and full of detail. Start looking at the tracklistings and dates in the booklet and you’ll be amazed at just how much Doráti managed to record in such a short time, with Mendelssohn and Mozart symphonies followed a month later by Respighi tone poems and Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben. The first disc couples Borodin’s gorgeous Symphony No. 2 with Stravinsky’s 1919 Firebird Suite, taped alongside music by Berlioz, Ravel and Debussy. Ravel’s Alborada del gracioso belies its age, and listen to how Doráti makes the processional in the second of Debussy’s three Nocturnes erupt, the Minneapolis brass let off the leash.

The big 20th century works all hit the mark, and it’s remarkable that so many would still been viewed as contemporary music in the early 1950s. A complete recording of Ravel’s Daphnis is excellent, and a famous 1953 version of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring is real edge-of-the-seat stuff; how on earth did Doráti persuade his orchestra to play with such precision and attack? Petrushka also oozes theatricality. Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra was famously recorded by Doráti in stereo with the London Symphony Orchestra, but this mono version has more bite.

The big 20th century works all hit the mark, and it’s remarkable that so many would still been viewed as contemporary music in the early 1950s. A complete recording of Ravel’s Daphnis is excellent, and a famous 1953 version of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring is real edge-of-the-seat stuff; how on earth did Doráti persuade his orchestra to play with such precision and attack? Petrushka also oozes theatricality. Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra was famously recorded by Doráti in stereo with the London Symphony Orchestra, but this mono version has more bite.

Doráti was the first conductor to record the three Tchaikovsky ballets uncut. His mono Nutcracker defies its years, Act 2’s sequence of short dances brilliantly characterised. Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake also hit the mark, though the most famous Tchaikovsky recording in the box is a 1955 version of the 1812 Overture, complete with a 1761 cannon borrowed from a museum added to the mix. Critic and broadcaster Deems Taylor provides a bonus spoken track taking us through the production process, the cannon accompanied by “a specially recruited crew of ordnance experts” with, er, medical staff on standby. Taylor also narrates Britten’s Young Person’s Guide and the Nutcracker Suite – he does a decent job, but neither work really needs him.

Doráti was the first conductor to record the three Tchaikovsky ballets uncut. His mono Nutcracker defies its years, Act 2’s sequence of short dances brilliantly characterised. Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake also hit the mark, though the most famous Tchaikovsky recording in the box is a 1955 version of the 1812 Overture, complete with a 1761 cannon borrowed from a museum added to the mix. Critic and broadcaster Deems Taylor provides a bonus spoken track taking us through the production process, the cannon accompanied by “a specially recruited crew of ordnance experts” with, er, medical staff on standby. Taylor also narrates Britten’s Young Person’s Guide and the Nutcracker Suite – he does a decent job, but neither work really needs him.

Intriguing novelties include Alberto Ginastera’s Variaciones concertantes, the solo variations nicely played, and a generous Respighi selection. The three Roman tone poems are exciting and seductive by turns, and it’s good to hear Church Windows once in a while. I’d not come across Morton Gould’s Spirituals for Orchestra before, and there’s the premiere studio recording of Copland’s Symphony No. 3, recently performed at this year’s BBC Proms. Doráti’s Beethoven (Symphonies 4 and 8) is clean-cut and witty, and there’s an affectionate, emotionally involving Brahms 3. Two discs 1954 LPs made with the Chicago Symphony are in the box, the second one containing a sharp-edged account of Bartok’s Miraculous Mandarin suite. Eloquence’s transfers, most taken from master tapes, are excellent, and each disc preserves Mercury’s attractive sleeve art. There’s a compendious booklet, stuffed with photos and session info. An engrossing collection and a handsome tribute to a still undervalued conductor.

Intriguing novelties include Alberto Ginastera’s Variaciones concertantes, the solo variations nicely played, and a generous Respighi selection. The three Roman tone poems are exciting and seductive by turns, and it’s good to hear Church Windows once in a while. I’d not come across Morton Gould’s Spirituals for Orchestra before, and there’s the premiere studio recording of Copland’s Symphony No. 3, recently performed at this year’s BBC Proms. Doráti’s Beethoven (Symphonies 4 and 8) is clean-cut and witty, and there’s an affectionate, emotionally involving Brahms 3. Two discs 1954 LPs made with the Chicago Symphony are in the box, the second one containing a sharp-edged account of Bartok’s Miraculous Mandarin suite. Eloquence’s transfers, most taken from master tapes, are excellent, and each disc preserves Mercury’s attractive sleeve art. There’s a compendious booklet, stuffed with photos and session info. An engrossing collection and a handsome tribute to a still undervalued conductor.

Ives: Concord Sonata Philip Bush (piano) (Neuma)

Ives: Concord Sonata Philip Bush (piano) (Neuma)

Charles Ives’s second piano sonata, formally titled Concord, Mass., 1840-1860 has a good claim to be his masterwork (although the Fourth Symphony would also have to be in the mix) and, in the opinion of pianist Philip Bush it belongs in a category with Bach's Goldberg Variations and the late Beethoven sonatas. It is certainly on a par with them in terms of sheer size: nearly 50 minutes of music, in four movements, with in places floods of notes that make it seem the descendant of Liszt and in others oases of simplicity that are the precursor of someone like Howard Skempton. In trying to depict the breadth of the New England Transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century Ives was nothing if not ambitious, and the seriousness of the enterprise shines through, although never far away from a moment of irony or humour.

Philip Bush has been engaged with Ives’s music since he was a teenager in the 1970s and this is evident in this performance, which is both technically flawless and interpretationally mature. Much of the Concord Sonata is notated without bar lines, so the precise pacing of the music, the use of rubato, the ebb and flow is everything. The third movement, “The Alcotts”, which starts with the utmost simplicity is fragile and sentimental, but is a hard-earned respite from the dissonance and hyperactivity elsewhere. The final movement, with its unorthodox appearance of a solo flute (Julia Parker-Harley), is pensive and engrossing. The sonata is paired with a composer roughly Ives’s contemporary, Marion Bauer. Her Six Preludes (1922) are modestly proportioned by comparison, and stylistically more conservative, blending Brahms, Rachmaninov but also with hints of ragtime. The preludes are good to hear and perfectly well played, but perhaps a slightly odd companion to the Ives. Without diminishing Bauer, putting Ives in the context of the prevailing music his time makes his achievement in the Concord Sonata only more astonishing. Bernard Hughes

Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition, Night on Bald Mountain Cleveland Orchestra/Lorin Maazel (Telarc)

Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition, Night on Bald Mountain Cleveland Orchestra/Lorin Maazel (Telarc)

Rachmaninov: Piano Concerto No. 3, Scriabin: Etudes Lang Lang. St Petersburg Philharmonic/Yuri Temirkanov (Telarc)

More vintage material exhumed from the vaults here, though a generation on from the Doráti box. The Telarc label was founded in 1977 and achieved acclaim in the early digital era – their 1979 digital LP of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture was, like Doráti’s a best-seller, Erich Kunzel’s Cincinnati Symphony update carrying a “Warning – Digital Cannons!” sign on its cover. Telarc stopped making new recordings in 2009, their extensive catalogue now owned by Concord Records. Some discs have been reissued and most are now available for streaming. Here’s a pair of LPs, both immaculately remastered and pressed on heavyweight vinyl. They sound marvellous in this format, and half the liner notes to Lorin Maazel’s Mussorgsky disc are devoted to details of the recording process. Maazel could be an erratic conductor, especially later in his career, but he made many superb recordings while music director of the Cleveland Orchestra (1972-82). He looks unusually happy on this LP’s back cover – and deserves to, as this is still a reference performance, taped in October 1978. I can’t make my mind up regarding Ravel’s orchestration of Pictures at an Exhibition, which in some performances seems like an uneasy marriage of refinement and earthiness. Maazel’s is a version to convince sceptics, opening with a swaggering trumpet solo and peerless heavy brass. Ravel’s string glissandi leap out of the speakers in “Gnomus”. The pacing feels unerringly right: “The Old Castle” has a delicious swing and Maazel lets his winds articulate properly in “Ballad of Unhatched Chicks”. “Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle” are well-characterised, Maazel reverting to Mussorgsky’s closing phrase rather than the Rimsky-Korsakov revision, a quirk I’ve only recently been made aware of. The “Great Gate of Kyiv” again features spectacular brass, Maazel ensuring that they never overwhelm everyone else - like Mercury, Telarc preferred to use a simple microphone set-up and leave issues of balance to the performers. As a curtain-raiser there’s an exciting version of the Rimsky-Korsakov revision of Night on Bald Mountain, the tacked-on soft coda exquisitely played. Exceptional, in other words, and the new vinyl pressing has ample presence.

The other LP is, unexpectedly, a live recording from the 2001 Proms which was originally released on CD but not on vinyl. Lang Lang was just 19 when he gave this performance of Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 3, accompanied by Yuri Temirkanov and the St Petersburg Philharmonic. Having the performance spread over three sides really allows the sound to bloom, apart from an irritating side break between slow movement and finale. The performance is terrific – Lang’s reputation has taken a pounding in recent years, but he’s on indisputably good form here. There’s no showboating, Rachmaninov’s first subject flawlessly phrased, the rapport between soloist and orchestra well judged. Lang knows when to step back, the soft low string line 1’15” nicely supported by rippling piano figurations. Temirkanov offers idiomatic support, stealing in imperceptibly after the big cadenza. The “Intermezzo” never feels overstretched, the fast central section full of life. Lang’s finale begins swiftly but never sounds garbled, Rachmaninov’s glorious second subject glowing, and the instantaneous applause at the close feels right. Terrific stuff. We get an appealing Chinese folksong as an encore, plus studio recordings of ten Scriabin etudes. I’m a little allergic to Scriabin’s orchestral excesses, but these occasionally flamboyant miniatures are a lot of fun. Lang nails each one’s essence, his playing unbuttoned in the wistful, romantic ones (try Op. 8, No. 11) and mischievous when he needs to be. Be amazed at the third of the Op. 42 set, Lang fluttering above the keyboard until he lands on the final staccato chord. Both reissues are well worth having, and hearing them on vinyl means that you’re compelled to sit down and listen properly, without pressing fast forward, skipping tracks or multitasking.

The other LP is, unexpectedly, a live recording from the 2001 Proms which was originally released on CD but not on vinyl. Lang Lang was just 19 when he gave this performance of Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 3, accompanied by Yuri Temirkanov and the St Petersburg Philharmonic. Having the performance spread over three sides really allows the sound to bloom, apart from an irritating side break between slow movement and finale. The performance is terrific – Lang’s reputation has taken a pounding in recent years, but he’s on indisputably good form here. There’s no showboating, Rachmaninov’s first subject flawlessly phrased, the rapport between soloist and orchestra well judged. Lang knows when to step back, the soft low string line 1’15” nicely supported by rippling piano figurations. Temirkanov offers idiomatic support, stealing in imperceptibly after the big cadenza. The “Intermezzo” never feels overstretched, the fast central section full of life. Lang’s finale begins swiftly but never sounds garbled, Rachmaninov’s glorious second subject glowing, and the instantaneous applause at the close feels right. Terrific stuff. We get an appealing Chinese folksong as an encore, plus studio recordings of ten Scriabin etudes. I’m a little allergic to Scriabin’s orchestral excesses, but these occasionally flamboyant miniatures are a lot of fun. Lang nails each one’s essence, his playing unbuttoned in the wistful, romantic ones (try Op. 8, No. 11) and mischievous when he needs to be. Be amazed at the third of the Op. 42 set, Lang fluttering above the keyboard until he lands on the final staccato chord. Both reissues are well worth having, and hearing them on vinyl means that you’re compelled to sit down and listen properly, without pressing fast forward, skipping tracks or multitasking.

Leopold van der Pals: String Quartets 1-3, In Memoriam Marie Steiner Van Der Pals Quartet (CPO)

Leopold van der Pals: String Quartets 1-3, In Memoriam Marie Steiner Van Der Pals Quartet (CPO)

One’s excitement at encountering a new composer can so easily be tempered by disappointment, and the realisation that their obscure status is probably deserved. Not here – reading about the young Leopold van der Pals’ encounters with Glazunov and Rachmaninov had me interested before hearing a note, and the two string quartets on this disc are well worth hearing. Van der Pals was born in St Petersburg in 1887 to Dutch/Danish parents (his father was a diplomat serving in the city), moving to Berlin in 1907 to study with Reinhold Glière. Van der Pals’ Symphony No. 1 was premiered there in 1910, before a promising career was derailed by the outbreak of war and exile in Switzerland, where he remained until his death in 1966. His String Quartet No 1 began life in 1917 and premiered six years later. CPO’s booklet essay, written by the composer’s great nephew Tobias, quotes extensively and movingly from van der Pals’ diaries, and it’s difficult not to hear his hopes and fears reflected in this distinctive, deeply personal music. You sense the unease in the first movement’s trudging march theme and anguished development section, the music dissolving into an “Andante con molto espressione” which eventually finds repose. An extended finale closes in a blaze of light, reflecting a diary entry in which van der Pals records that “…it is still fortunate that I can work despite everything… underneath all the heaviness there is beauty. Nature and art.”

Quartet No. 2 followed in 1925. It was never performed in public, Tobias van der Pals suggesting that the quartet’s darker corners may be a musical response to the death of the Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner, who the composer had known well since his Berlin years. Themes are developed and repeated across its four linked movements, and as with the earlier work there’s a powerfully affirmative conclusion. A compact, entertaining Quartet No. 3 from 1929 is subtitled ‘Metamorphosen”, the first section’s melodic idea recurring, transformed, in the following three movements. As a bonus, there’s In Memoriam from 1948, composed after the death of Steiner’s widow and performed at her funeral. It’s a beautiful work, slowly infolding over an ascending viola line. This is an enthralling disc, wonderfully engineered. Rich, passionate playing too, from the Swedish string quartet who’ve made it their mission to promote van der Pals’ music. He wrote six quartets, so bring on Volume 2.

Emmanuel Despax: Après un rêve: Belle Époque: Nights at the piano – music by Fauré, Poulenc, Debussy, Saint-Saens, Chaminade, Ravel, Duparc Emmanuel Despax (piano)(Signum)

Emmanuel Despax: Après un rêve: Belle Époque: Nights at the piano – music by Fauré, Poulenc, Debussy, Saint-Saens, Chaminade, Ravel, Duparc Emmanuel Despax (piano)(Signum)

This well-chosen and characterfully played collection of French music for solo piano by seven composers, from UK-based French pianist Emmanuel Despax is a delight. Just one pedantic quibble to get out of the way first: the use of the phrase "Belle Époque" in the title. It is somewhat "tiré par les cheveux" to refer to a period which began in around 1880 and had definitely ended by 1914 to include Saint-Saens's Danse Macabre, written before it, in the 1870's, or the delightful 1925 Nocturne by Cécile Chaminade, or indeed Poulenc's entire set of the Soirées de Nazelles, only completed in late 1936, by which time Léon Blum was already President of France, and Jean Renoir had started filming La Grande Illusion. That said, this performance of the Poulenc could well become a reference version. Compare it with, for example, Pascal Rogé's mid-1980s version for Decca, and whereas Rogé tends to be showy, even 'sportif', Despax finds much more darkness and depth in these pieces, giving them room to breathe and to tell their (short) stories. There is technique to spare too: the speedy hand-crossing in "La Suite dans les Idées" has an astonishing ease, and the insouciant lightness of "Le Contentement de Soi" is joyous. "Clair, pointu et sec", is the marking on the score at one point in that piece; Despax does exactly what it says on the tin.

The Saint-Saens Danse Macabre (arr Liszt/Horowitz) has everything from evanescent will o' the wisp sparks to huge crescendi, all linked by a very strong sense of the story-line. Despax has the benefit of the dynamic range of a Fazioli piano, the recording made at the concert hall of the Menuhin School in Surrey. The three monster-pieces of Ravel's Gaspard de la Nuit also receive fine performances. Despax has included texts for the listener to read along with each of the tracks, and there is a backstory here. The pianist is the grandson of poet Jacques Charpentreau (1928-2016), to whom the collection is dedicated. Charpentreau was a teacher of French and a prolific "homme de lettres". He wrote over forty volumes of original poetry, and works as diverse as "Chats!" (the French published version of T.S. Eliot's "Old Possum"), and even biographical monographs of Gilbert Becaud and Charles Aznavour. This CD (somehow!) packs in more than 82 minutes of music. Despax is fluent and totally convincing throughout. Recommended. Sebastian Scotney

Add comment