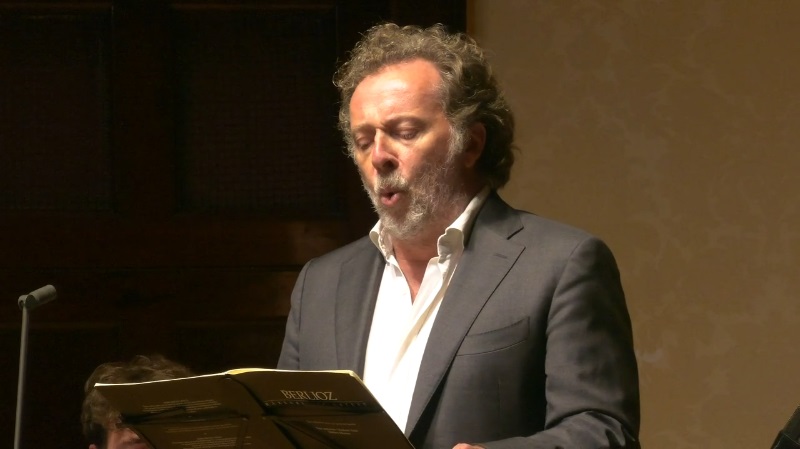

Christian Gerhaher and a string ensemble led by Isabelle Faust presented here a programme of works with a nocturnal theme. Gerhaher’s voice is an instrument of husky shadings and dark hues, so the night theme seemed wholly appropriate. The impetus for the programme, which the group is touring to several countries, was a new arrangement by David Matthews of the Berlioz Les nuits d’éte, with string sextet accompaniment, but the most interesting work was the first, Othmar Schoeck’s Notturno, op. 47.

Schoeck composed the cycle, for baritone and string quartet, in 1931-3. The composer himself was Swiss, but had studied in Germany with Max Reger. His music is rooted in German Romanticism, with considerable harmonic and contrapuntal complexity – the strings do far more than accompany here – but there is also a feeling of restraint, as if everything is happening on a predetermined scale of expression. All of which suits Gerhaher very well. He is a versatile singer, capable of Wagner, but more at home on the recital stage. His sound is utterly distinctive, but hard to describe. Even when singing with broad tone, he has a nasal quality, but its hardly constrictive.

Just as often, he brings the sound down to a conspiratorial parlando, often craning over the stand towards the audience, as if whispering a confession. After hearing Gerhaher sing Schoeck, it is hard to imagine it being done any other way. The scoring, though, suggests a bigger voice, and the strings often matched Gerhaher in volume, though rarely smothered him. Technically, you could fault him on a number of counts. Those speech-like passages are often accompanied by a flattening of pitch, which stood out when he sang in unison with the sustaining strings. He also drops away from long notes, especially at the ends of phrases. But the work is about more than the singer. The second movement (of five), and a large section of the first, don’t involve the singer at all. In these passages, we hear complex counterpoint, but also startling portamento effects and complex, unpredictable chord sequences. Notturno is a great vehicle for Gerhaher, but it is also much more than that.  It’s not often that the lollipop on a concert programme is the Schoenberg, but the most popular work here was his Verklärte Nacht. In the Schock, the cellist was Jean-Guihen Queyras, and when the group was expanded to sextet for the Schoenberg and Berlioz, the additional cellist was Christian Poltéra – luxury casting! Verklärte Nacht really benefited from this top-class cello pairing. It is a bottom heavy score, and the tone and texture are determined by the cellos. Both brought rich, dark colouring, but always controlled and with excellent articulation and phrasing. That set the tone for a powerful and richly hued reading. The quietest passages, including the beginning and end, were played at a whisper, and the louder passages shone with clear, focussed intensity. Surprisingly, Isabelle Faust didn’t match the clarity or precision of her ensemble. Her intonation at the top was shaky, and her tone on the G-string was dry.

It’s not often that the lollipop on a concert programme is the Schoenberg, but the most popular work here was his Verklärte Nacht. In the Schock, the cellist was Jean-Guihen Queyras, and when the group was expanded to sextet for the Schoenberg and Berlioz, the additional cellist was Christian Poltéra – luxury casting! Verklärte Nacht really benefited from this top-class cello pairing. It is a bottom heavy score, and the tone and texture are determined by the cellos. Both brought rich, dark colouring, but always controlled and with excellent articulation and phrasing. That set the tone for a powerful and richly hued reading. The quietest passages, including the beginning and end, were played at a whisper, and the louder passages shone with clear, focussed intensity. Surprisingly, Isabelle Faust didn’t match the clarity or precision of her ensemble. Her intonation at the top was shaky, and her tone on the G-string was dry.

Berlioz’s music thrives on instrumental colour, so reducing his orchestration is asking for trouble. In fact, Les nuits d’éte started out as a cycle for voice and piano, which Berlioz then orchestrated, so David Matthews’s new arrangement for string sextet sits somewhere in between. Gerhaher gave another reading that began with the words, sung in impressively idiomatic French, with the musical line a colouring to his shapely phrases. Again, phrases often drifted under the pitch towards the end, and sustained climaxes seemed to be deliberately curtailed. This time, the more modest scoring laid those traits out bare. In Matthews’s hands, the instrumental textures remain very much accompaniment. He distributes the music subtly, for example bring the sextet down to a string quartet for extended passages, but then adding in the two extra instruments as pizzicato lines. Most of these songs are dark and sombre, which again suits Gerhaher’s gaunt tone. But Berlioz ends on a high note. His last song, “L'île inconnue,” is broad and radiant. Matthews voices the textures broadly, and Gerhaher follows suit, finally putting the full weight of his tone behind the lines. A bright end to a distinctly gloomy evening.

Add comment