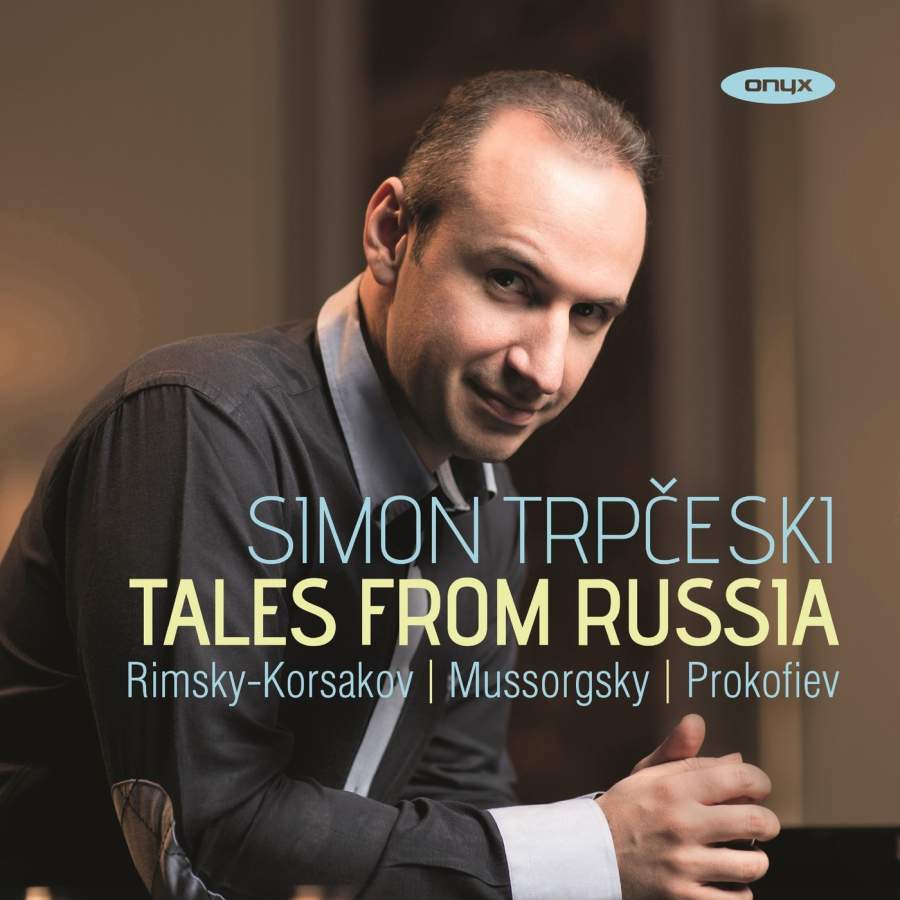

When Macedonian pianist Simon Trpčeski first bounced on to the concert scene, he seemed part will-o-the-wisp, part jack-in-the-box, a real personality of coruscating brilliance. Time has passed, and deeper, more reflective qualities have emerged alongside the fireworks, an impression very much underlined by his intent in launching his latest CD with Prokofiev's Tales of an Old Grandmother - short, predominantly introspective miniatures which are difficult to place in a concert programme. Indeed, I'd not heard them in that context until last night, where their place at the start of an extraordinary Russian second half mirrored the beautiful introspection of Brahms's Schumann Variations at the start of the first.

Trpčeski’s elasticity and freedom take you on unpredictable journeys, even in works you know. Which is, oddly, not the case for most of us in Brahms's early homage to Robert and Clara, overshadowed by the later Handel and Paganini variations. Schumann’s own whimsy and love of quotations is reflected in the accumulating references as the work glides from the F sharp minor of the intimate, sorrowful theme – from Schumann’s Bunte Blätter, already subjected to variation form by Clara herself – into sunnier uplands. Trpčeski kept the work poised between the improvsatory feel at which he excels and absolute clarity in Brahms’s abundance of surrounding figurations.

It was only when Trpčeski played the lullaby-like A flat major Waltz from Brahms’s Op. 39 set as his third encore that I realised what I’d rather have heard to follow – that entire sequence, rather than three of Liszt’s Soiréees de Vienne, composer in 1852 two years before Brahms’s variations and subtitled “Valses-caprices d'après François Schubert". The flash of Liszt is a long way from the candour of Schubert, and even thid selection could seem to outstay its welcome, though again Trpčeski kept it unpredictable and eventually buoyant, making light of the filigree; he certainly knows how to spring a dance.

In future programmes, Trpčeski could even pair thesehomages with Prokofiev’s Schubert waltz transcriptions. Here, though, the Tales of an Old Grandmother as anchor to an otherwise wild and dangerous post-interval journey, was inspired, and the most melodic (and briefest) of the four, the Andantino, proved as close to hushed concert-hall magic as you can ever get. Then the witches and demons of Musorgsky’s Night on the Bare Mountain swarmed in, but spruce and clear, Trpceski saving real savagery until the later stages before the poetic – and infinitely extended – shepherd’s piping of the dawn epilogue. This is Konstantin Chernov’s arrangement of the Rimsky-Korsakov version, still – for all the clamouring of Musorgsky authenticists - the best. You felt that Trpčeski, who liked to instruct one hand with the other when it’s free, could probably make a good conductor of this and other Russian fantasies.

In future programmes, Trpčeski could even pair thesehomages with Prokofiev’s Schubert waltz transcriptions. Here, though, the Tales of an Old Grandmother as anchor to an otherwise wild and dangerous post-interval journey, was inspired, and the most melodic (and briefest) of the four, the Andantino, proved as close to hushed concert-hall magic as you can ever get. Then the witches and demons of Musorgsky’s Night on the Bare Mountain swarmed in, but spruce and clear, Trpceski saving real savagery until the later stages before the poetic – and infinitely extended – shepherd’s piping of the dawn epilogue. This is Konstantin Chernov’s arrangement of the Rimsky-Korsakov version, still – for all the clamouring of Musorgsky authenticists - the best. You felt that Trpčeski, who liked to instruct one hand with the other when it’s free, could probably make a good conductor of this and other Russian fantasies.

On the CD, the longest work is a fully-fledged piano version of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade, which works amazingly well. Here battle continued on a personal level with the painful conflicts of Prokofiev’s Seventh Sonata. The first movement would benefit from a more integrated speed in the second subject’s melancholy dreams, here feeling more like a slow movement within the whole, and the best interpretations of the final start, as Prokofiev’s mezzo-piano suggests, like a tiger waiting to spring; Trpčeski’s unstinting resonance on the blue-note bass gave us too much too soon, though as a tour de force hitting nearly all the notes, this rightly brought much of the audience to its feet. The central Andante caloroso really struck the depths, though, with the painful minor-second tolling bells conveying the full horror of both the Second World War and the Soviet regime through which Prokofiev was then living, and enduring.

Lighter was the Prokofiev double-encore, the sprightly March from his 1935 Music for Children followed immediately by an early spin through more playful demonic territory, the Humoresque-Scherzo of the Op. !2 Ten Pieces. The Brahms waltz might have been a poetic place to lay the evening to rest, but we got one more Humoresque, Shchedrin’s, which could have been merely funny-silly, but again Trpčeski raised it higher with his artistry and sense of fantasy.

Add comment