Rattle and the Berliners went home at the beginning of the week with vine-leaves in their hair. There's now something else to celebrate. Exactly one week on from the second concert in their Sibelius cycle, the Barbican hosted even more of an all-out stunner, starting with Sibelius no less compellingly conducted than the best of last week’s symphonic cycle and ending with a performance of the "Inextinguishable" Fourth Symphony by this year’s other 150th birthday composer, the great Dane Carl Nielsen, which electrified from start to finish.

In his first ever concert with a major London orchestra back in 2011, Finn Sakari Oramo gave an interpretation of Sibelius’s Third Symphony which Rattle last week couldn’t touch for depth and strangeness. That concert – also featuring his wife Anu Komsi in Sibelius’s creation myth Luonnotar and songs by Kaija Saariaho, as well as a slice of his favoured English music in Bax’s Tintagel – was enough to convince the BBC Symphony Orchestra to make him their next chief conductor. The relationship has blazed so far, and this season offers superlative programming to go with the six Nielsen symphonies.

We met at Maida Vale after Oramo and the orchestra had spent a long day rehearsing for the third concert in the series. We chatted first about Garrick Ohlsson’s stupendous performance of the Busoni Piano Concerto in the second back in December – a definite highlight of 2014 – and about the replacement for Yevgeny Sudbin, Federico Colli, who had been at the rehearsal of Rachmaninov’s Third Piano Concerto (“he has a big imagination, which that piece needs”). Then the interview began. It took me a while to realize not to jump in too much while Oramo (pictured above at the Proms by Chris Christodoulou) revealed his Finnishness in characteristic pauses for thought (watch any Kaurismäki film if you don't know what I mean).

We met at Maida Vale after Oramo and the orchestra had spent a long day rehearsing for the third concert in the series. We chatted first about Garrick Ohlsson’s stupendous performance of the Busoni Piano Concerto in the second back in December – a definite highlight of 2014 – and about the replacement for Yevgeny Sudbin, Federico Colli, who had been at the rehearsal of Rachmaninov’s Third Piano Concerto (“he has a big imagination, which that piece needs”). Then the interview began. It took me a while to realize not to jump in too much while Oramo (pictured above at the Proms by Chris Christodoulou) revealed his Finnishness in characteristic pauses for thought (watch any Kaurismäki film if you don't know what I mean).

DAVID NICE: Did you devise the programmes for all six concerts?

SAKARI ORAMO: Yes.

So you clearly wanted works from around the periods when the Nielsen symphonies were composed?

I did. And Rachmaninov is somehow a watershed figure in all of this, that’s why he’s so present in the Spring Cantata and Third and Fourth Piano Concertos. Not because he would be especially akin with Nielsen, but his life somehow followed a similar path, if you think about going from the world of the First Piano Concerto and Nielsen’s First Symphony to Nielsen’s Sixth or Rachmaninov’s Fourth Concerto, they both are on a similar track of blossom to reduction and heartfelt drama to irony and all that, they take a similar emotional path.

What struck me from the start – I’ve been teaching a course linked with the symphonies – was that while I’d thought, it will get really interesting when we get to the “Four Temperaments” [the Second Symphony], but actually the First is already a fully fledged work of great individuality, isn’t it? It grabs you by the throat right at the start.

Yes, immediately, though not all of it works so well. From the Second on everything works.

What do you think are the weaknesses of the First?

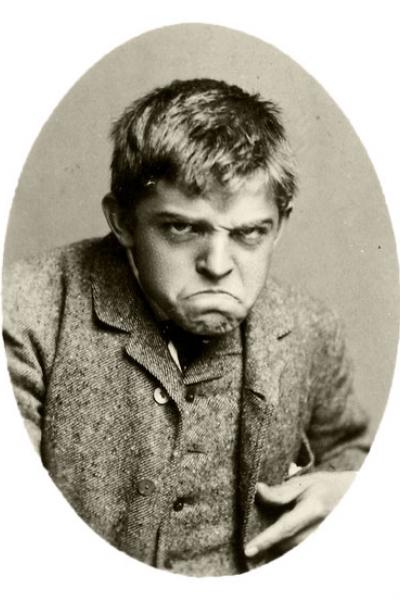

In some way it just feels like Nielsen’s found this fire which he plays with, and it just goes off into several directions at the same time, which in a symphonic work isn’t necessarily so good [Nielsen being prankish in his youth pictured left, courtesy of the National Library Copenhagen]. And I also feel the finale doesn’t somehow live up to the expectations of the other three movements.

In some way it just feels like Nielsen’s found this fire which he plays with, and it just goes off into several directions at the same time, which in a symphonic work isn’t necessarily so good [Nielsen being prankish in his youth pictured left, courtesy of the National Library Copenhagen]. And I also feel the finale doesn’t somehow live up to the expectations of the other three movements.

Do you think it’s fair to say it’s a direct offshoot of Brahms in a way?

Absolutely, oh yes. There are other influences too. But Brahms was still very near, he had died just a couple of years earlier.

And even with the Third – which I’ve been listening to today and I’m going to teach it tonight – there’s a lot more unexpected, very contemporary harmonic twists that make you realize that despite the occasional romantic colours it's very much a 20th century symphony.

Totally 20th century, yes. And then it’s got this uncanny Elgarian swagger in the last movement, which is totally unexpected.

Well, do you know when we covered the Second in class last month, something about the way the theme in the finale transforms itself into the march struck me, and it’s exactly the same theme as the trio of Elgar’s Second Pomp and Circumstance March.

Sure, I hadn’t got that actually.

I don’t suppose Nielsen knew it.

He might have. I wouldn’t be surprised if Nielsen would have known Elgar, because he must have played it as an orchestral musician. I don’t know exactly what the history of that is. There must be some connection there.

It’s wonderful to space out the cycle through the year, and the fact that you’ve got works from roughly the same period as each symphony, does that make you think more about the context? I’m fascinated by how many great works first appeared, for example, in 1911, around the time of the Third.

Of course there would be all the Second Viennese School too. But Nielsen has so little to do with that – he wasn’t so interested. And also one motivation behind this programme this week is that I wanted to do one of the six as a normal concert – traditional overture, concerto, symphony. And the Third Nielsen somehow suits that approach best because it’s the longest, the most substantial and it lives well with other music, which can’t be said for some of the other Nielsen symphonies which are quite hard to couple with anything.

I’ve never thought of the “Four Temperaments” going into a first half before, because although in actual timing it’s quite short it feels, particularly in your performance, as if it covers a lot of ground.

It can work in a first half, especially with the Busoni Concerto in the second.

Yes, and it did, but that was a generous concert. [BBCSO General Manager] Paul Hughes likes to do four-work concerts, that’s how you started, isn’t it, with the Sibelius/Bax/Saariaho programme?

He does. He’s never opposed to that. I think it’s a good way of putting together pieces that would be too short in their own right in one half, so adding couplings like that can help.

Next page: lessons learned from Nielsen and the BBC Symphony sound

Well, this is a good case in point – I can’t remember ever having heard [Sibelius’s tone-poem] The Dryad, with which you’re starting, in a concert programme before, where would it go? It’s a short piece but covers a wealth of ideas…

…which all fly past very quickly. I don’t know actually why Sibelius wrote it and what he was thinking. It feels like an exercise, for something like the Third Symphony, perhaps – it could be drop-off material from the Third.

It sounds closer to the world of the Fourth.

Sure, also, yes. Of course there is an Op 45 No 2, the Dance Intermezzo, which you could also include, but in this instance I didn’t feel it would add anything specific, so I chose not to do it.

This must be a very rich year for you in that you’ve conducted the Sibelius symphonies many times and also the Nielsens – I remember when you were principal conductor of the CBSO you did a wonderful Fourth and Fifth. But suddenly to find them in conjunction, has it taught you anything?

This must be a very rich year for you in that you’ve conducted the Sibelius symphonies many times and also the Nielsens – I remember when you were principal conductor of the CBSO you did a wonderful Fourth and Fifth. But suddenly to find them in conjunction, has it taught you anything?

The more you think about Nielsen and the more you approach the music, the more you appreciate the incredible imagination and skill, and the more you also wonder why he hasn’t become such a regular feature in the concert repertoire as Sibelius has in most other countries. I recorded all six Nielsen symphonies in Stockholm [with his other orchestra, the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic], which was a good preparation for this run. That’s an orchestra with a long Nielsen tradition, but it hasn’t had much exposure to the symphonies in the last 10 or 15 years. What has it taught me? Even things that seem impossible to perform are solvable in Nielsen. There’s stuff in the Sixth that is completely impossible, actually, on paper, but somehow you can get past it.

How?

By ignoring the constant quest for note-perfect-ness, more to look at the shape and the notes will take care of themselves.

And the atmosphere and the spirit.

Yes, crazy, crazy spirit.

Here you have players who are famous for sight-reading anything quickly. Does that make a difference?

Of course it does, everything is quick and also with the BBC Symphony it’s very inspiring because they respond immediately to everything [clicks fingers], nothing seems impossible.

It seems to me that first concert with Luonnotar, and your wife [soprano Anu Komsi], that was the best I’ve ever heard it, unearthly-beautiful, and Bax, the Sibelius Third and some Saariaho. Did that feel major to you or just another concert?

Just another concert. It was a good concert, I enjoyed it. But I was extremely surprised to be asked to come here as chief conductor after that. I think it was just a question of good timing as well. But it was the first time I ever conducted a major London orchestra. I’d only ever worked with the London Sinfonietta, and that’s 20 years ago.

You’d appeared at the Albert Hall…

With CBSO and Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra and the Stockholm Phil, yes [and now he's conducted his first Last Night with the BBC Symphony Orchestra - pictured left as violinist with Janine Jansen by Chris Christodoulou]. So it was a funny situation. But of course I’m very grateful that it could happen.

With CBSO and Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra and the Stockholm Phil, yes [and now he's conducted his first Last Night with the BBC Symphony Orchestra - pictured left as violinist with Janine Jansen by Chris Christodoulou]. So it was a funny situation. But of course I’m very grateful that it could happen.

So what did you immediately think about the sound of the orchestra and what do you think you can do with them now?

I was pretty impressed actually with their sound and attitude already then, and I think much of it actually owes to Bělohlávek and his work. His aesthetic background is I feel somehow similar to mine. He’s a string player, a cellist [Oramo is a violinist], and he’s got this middle-European sound ideal, which I still find works in the orchestra and I’m happy to build on it.

He transformed the string sound beyond belief, particularly with his Mahler series.

Yes. And I think it’s the first time I’ve come to an orchestra with a sorted string section. Always before I had to work a lot with the strings and now it’s like it’s all there. Of course there’s always things to do, but in the big picture it’s a luxury to have this adeptness to all sorts of different things.

I suppose the problem for us is that the Barbican is not a place where you can really get depth. Were you in Birmingham [as the CBSO’s chief conductor between Rattle and Andris Nelsons] when the new hall was up and running?

Yes. Now even Paris has a fantastic hall. I had a look on the internet at the opening concert last night. Of course you can’t gauge the sound but it looked fairly impressive. I think London is lagging very much behind in that sense.

It’s a shame that plans for a new concert hall for the BBC Symphony in White City folded.

Well, would it have been ideal? I’m not sure.

What do you have to do in the Barbican to adjust?

I haven’t actually paid any attention to it, you just do what you do, and we only have rehearsals there on the day, which is far from ideal. The other orchestra I work with, the Stockholm Philharmonic, rehearse in their own hall.

A beautiful 1920s building.

It’s a good acoustic, it’s been recently improved by some minor adjustments. It’s a whole different ball game. I admire what this orchestra does, in this situation [at Maida Vale, for rehearsals], it’s very diffuse, it’s very hard to tell what people are actually doing, and probably the worst problem is it’s very tiring for the ear. I’m probably not used to it, but I stop hearing detail, I just hear a wash, which can be difficult.

So you mean you’re straining with your ear to try and hear more?

Yes, I think that’s the process. So in these conditions this orchestra is doing a marvellous job.

You’ve already done great work with other symphonies – the Shostakovich Five, the Beethoven Eroica – that seemed to catch light. You seem very genial with the players. Are you relaxed with them?

You’ve already done great work with other symphonies – the Shostakovich Five, the Beethoven Eroica – that seemed to catch light. You seem very genial with the players. Are you relaxed with them?

I feel one of them. In a way, of course, as a string player, I am. It’s a terrible waste of energy not to connect with players. Somehow the thing that makes an orchestra click is not necessarily being told exactly what to do, it’s rather being enticed to do something and without them even knowing ending up somewhere nice. That’s the best situation. Of course you’ve got to work up to it somehow.

Do you give them a certain amount of freedom? I mean, you’ve got a fantastic wind department, I think they’re possibly the best in the country.

That’s really good to hear, because I really like them, it’s a fantastic section. Of course I take everything they can give. But somehow it always slots into my thoughts anyway. I don’t find a big discrepancy between giving wind players freedom to play their solos and still integrating it into a convincing hall. But yes, we all breathe the same air.

Next page: special concerts, Finns hidebound in Sibelius and contemporary music

It’s musicianship and it’s not showing off for showing off’s sake, which sometimes can happen in the very big name orchestras, "I play the solo like this today just because I can". That’s not the attitude here. I’ve had some experiences with very big orchestras where it’s so free that you start wondering, what’s the point, where’s the beef? And that can be hard to integrate and do something convincing.

You have to take just what Sibelius wrote and make the most of it, and it will work, mostly, very well

Has anything you’ve done with the orchestra so far really amazed you, or have you just been pleased with it all?

I think probably the best concert for my money that we’ve actually done together has been away, in Spain, in Saragossa, where there’s a very good hall, and we did a Shostakovich Five but with practically no rehearsal, only with the strength of the performance we did here before. That was amazing, because suddenly there was this depth, it was all there, just because the hall was good, and they were also very fired up as well. It was also probably that the piece had worked itself over a period of time. And they really wanted to show what they could do. It was pretty amazing. And in those best experiences for a conductor, from my point of view, it’s just the feeling that you don’t any more have to do anything, you just let them do it.

Because the work has been done?

Yes, or rather the work has fulfilled itself somehow in the consciousness of everybody. But I think everything I’ve done with them so far has actually been a positive experience compared to what I was expecting. It’s quite incredible. It’s obviously working. I just wish we would have even more people listening to us live. The Proms is great…

You didn’t have the worst of it. The wonderful concert with Josep Pons, I’ve never seen fewer people in an audience. Maybe it wasn’t easily sold, though it was a lovely programme.

If someone knew what was sellable they’d make a lot of money, I suppose. The season itself isn’t marketed properly, it seems to me, though I’m no expert in this field.

Interestingly there were a lot more people for the Busoni – the buzz was that there hadn’t been a performance since 1988.

Which in a way gives confidence to put on something like that. We are in a difficult slot on the market in a way, and probably some new thinking and even some new money would do us good in that department.

Instead of which there will be further BBC budget slashes, even for the Proms.

And the orchestra is feeling it as well, which I think is a great shame. For all the great work they do they should be properly supported.

There is an audience for the sort of programmes you’re doing and it’s a young audience. The Rest Is Noise festival at the Southbank brought younger listeners, and the LPO under Jurowski seems to have kept them. How is it in Stockholm and Helsinki?

Stockholm has been a growing tendency. I still think the audience is probably a little bit older, but there’s nothing wrong with that.

I think the PRs’ mistake is to discount the core audience, which will be older.

Exactly. But there have been openings also for younger audiences in Stockholn, and they work pretty well – these six o'clock concerts with just one piece and such like, it does work – despite the total blackout there is in the Swedish press at the moment. They’re not writing anything about classical at all. It’s like total death compared to what happens here.

We’re losing our arts pages here.

Yes, there is the same kind of development but there is still a lot here, both in the papers and online.

And in a concert scene where you’ve got six or seven events a night, you’re never going to cover them all. Did you feel in Birmingham that there was a very loyal core of people? I found that with the talks I give them there – they all come. There’s a real feeling of community.

Yes, it’s a more diffuse picture here, and different kind of target groups. The Birmingham community is a legend – it consists of people who were mostly brought up by Rattle to listen to many different things, and they’ve remained incredibly supportive..

You did a lot of British music in Birmingham – Gilbert and Sullivan, for example. Would you like to do more?

Probably not G&S again. But I did also John Foulds, Constant Lambert, Vaughan Williams symphonies, the obvious Elgars.

Was that an interesting test for the Swedes [with whom Oramo has recorded Elgar], who presumably didn’t know the Elgar symphonies well?

Was that an interesting test for the Swedes [with whom Oramo has recorded Elgar], who presumably didn’t know the Elgar symphonies well?

I took an approach whereby we took a lot of time discussing the style, not always playing the notes, but going through what is behind them, and I think the results are quite interesting. Because I think they found the style incredibly well, better than you would ever imagine possible from an almost non-existent background. Which tells a lot about Elgar being universal. When you take it to the point of understanding what he’s written, there’s nothing too strange.

The string writing is unbelievable.

So beautiful, the flourishes and divisions.

Do you feel Sibelius is more or less on an even keel, or is that also a challenge every time? Because you must have done that a lot more than Nielsen.

Yes. One of the very best Sibelius performances I’ve ever been involved with was in Rome, with the Orchestra of the Accademia di Santa Cecilia, who played a fantastic Fifth Symphony, and I don’t know exactly how it happened, but I think the Italian musicians, they have this love for small designs, and they brought such beautiful detail. Without the burdens of the past, because when you do Sibelius with a Finnish orchestra, it always strikes you that they play either [the interpretations of conductors] Berglund or Segerstam or Saraste, but not really actually what comes from Sibelius. There are thick layers of stuff which are all adequate and work well, but it’s not what I’m interested in doing.

So you find it difficult to scrape that off?

It’s impossible, actually, because the materials are full of markings and – you should actually just have what the composer wrote, a couple of bowings, and then you work it with the ears, which is what I’m trying to do here – clean materials, no additions, no reorchestration, no altered dynamics…

Because wasn’t it Berglund who said Sibelius needed to be touched up?

I think he was intrinsically wrong, although I admire his imposition – I loved playing for him as a violinist, but I still think his basic thesis was wrong.

Because you think it can still work on its own?

It totally does, but of course you’ve got to have incredibly intelligent musicians to do it, and you’ve got to have the idea as a conductor how you can relate the problems that arise to what’s actually sounding and coming out. But a lot of times Sibelius seems to have meant for his details to be kind of inside, a kind of veiled presence of pedal tones, and to just rip them away like that, to take all the long tones down, it’s too obvious for my taste.

So the fundamental difficulty is getting the layers right.

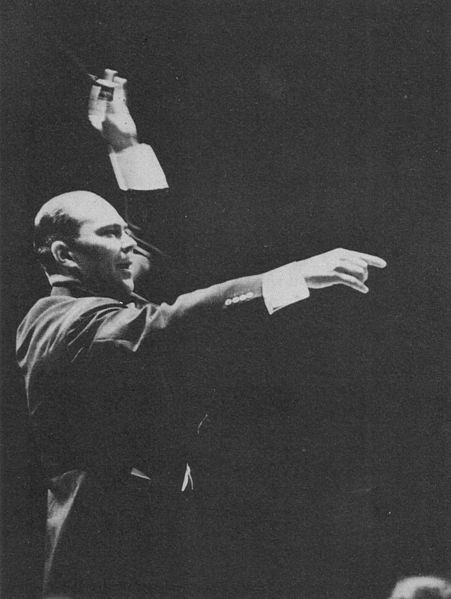

Absolutely, and that’s what Berglund [pictured right in the 1960s] was trying to do all his career, and he did fantastic work. But there’s no-one else that can follow on that. You have to take just what Sibelius wrote and make the most of it, and it will work, mostly, very well.

Absolutely, and that’s what Berglund [pictured right in the 1960s] was trying to do all his career, and he did fantastic work. But there’s no-one else that can follow on that. You have to take just what Sibelius wrote and make the most of it, and it will work, mostly, very well.

It strikes me that – or did, actually, until today when I heard In memoriam, which isn’t a great piece – whether they’re miniatures or full scale works, and there’s an enormous amount, isn’t there, that it’s all beautifully crafted, original, inventive, that he could take a miniature and lavish such attention on it. It doesn’t seem that there’s any bad Sibelius.

Not really, apart from maybe the very early pieces and some of the incredibly late pieces, but no, nothing’s bad.

Or un-individual.

Exactly. But clearly you can see that he was more interested in finishing and polishing some pieces than others, polishing the Fourth Symphony, letting them grow. Some of the miniatures and tone-poems seem somehow a little less loved.

Is it possible to say which are closest to your heart, or is it whatever you’re working on at the time, which is the usual answer?

It’s really hard to say. In terms of pieces by Sibelius everything is good, and if it’s not good, I don’t do it.

And Nielsen?

The same.

So there’s not one symphony that when you come to it you think – ah, this is it?

No, because they all have different characteristics and virtues and all of them have so much to explore. And both Sibelius and Nielsen actually tolerate a lot of different approaches in interpretation, so it’s not that you’re following one certain path.

Tempi don’t have to be exactly as marked…

So long as they grow organically from one another.

And it’s that organic growth which is so fascinating – the second and third movements of Nielsen’s Third Symphony, for instance – the third is like a thicket and I can’t work it out but it flows.

It does, it’s quite weird. The Third Symphony, all the movements except the second are in the same tempo [sings and clicks fingers to keep time]. It makes a unity. But the Third Symphony orchestrally is the least hard of the six to conduct.

There’s still a lot of vigorous string quaver writing which is always on the move and seems so hard.

It is, but it’s much less hard than say the Fifth which is quaver triplets and such, that’s hard.

What is unplayable about the Sixth?

Oh, so much. A lot of the variations are actually terribly hard and uncomfortable.

Should it sound uncomfortable?

No, not Nielsen, I don’t think. Richard Strauss was different. He always wrote extremely difficult textures if he wanted to make the music sound anguished. But Nielsen wasn’t like that.

You’re doing the whole sequence of both sets of symphonies in Stockholm.

I’m not doing everything – I would die. But it’s both composers together, but they only meet once – the Fourths meet in one concert. Otherwise they are put in context which is suitable for each piece. We’re starting with Tchaik Six, Nielsen One, I’ve forgotten, I haven’t thought about it for such a long time. But I think the strength of the Stockholm concept is that it’s on consecutive days, so you can absolutely follow the narrative of both composers from beginning to end. We’ve done things like that before, in 2011 we did a 10 day Mahler festival with a different symphony every day.

With different conductors...

And orchestras. Which was an incredible journey. I did First and Eighth with my own orchestra, and with the Finnish Radio Symphony the Third and Fourth, and there were others too to fill in the gaps. But it’s the strength of an organization like that that we can actually bring together everyone in Scandinavia and create something like that which is totally out of the ordinary.

And after this season here do you have divulgeable plans?

Everything is not yet quite ready, but I don’t think there will be a season that’s quite as tight as this thematically. There will be big and small pieces and something slightly unusual, but not linked together.

Is there anything in the contemporary sphere which you particularly want to devote time to with this orchestra?

We do so much anyway, and contemporary music nowadays is such a wide field, but just recently I did a studio recording of a really interesting piece by a Latvian composer, Onutė Narbutaitė, she is interesting and writes beautifully for orchestra, you hear fantastic things. That has yet to be broadcast. Interesting things are happening in the Baltic. It’s good…

And there’s no longer an orthodoxy of style.

It’s good – I enjoy the situation now much more than I did 20 years ago. But in a way my role as a chief conductor is, yes, to occasionally bring in new composers we’ve not heard of – and there will be new works in some of my programmes next season - but also to take care of the orchestra’s ground repertoire, that’s the most important part of my work at the moment. And I don’t know if it’s the right choice, but it feels right at the moment.

It’s good – I enjoy the situation now much more than I did 20 years ago. But in a way my role as a chief conductor is, yes, to occasionally bring in new composers we’ve not heard of – and there will be new works in some of my programmes next season - but also to take care of the orchestra’s ground repertoire, that’s the most important part of my work at the moment. And I don’t know if it’s the right choice, but it feels right at the moment.

Well, I remember when David Robertson conducted Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, they hadn’t played it for 15 years, so it’s possible to hear those sort of works afresh.

It’s good for them. When I was with Finnish Radio as chief conductor, I did so many premieres, now I don’t have to do so many.

It was sometimes an obligation rather than a pleasure?

There’s always the good ones and you can never know when you start.

So when you start on a piece and it really isn’t up to scratch, you have to be professional…

Of course, you make the most of it, and try to bring out whatever there is – there’s always something, whether it’s enough is another question. I hate just to be patronising, there is fantastic composing going on, possibly more than some decades before, but it’s almost a complete joke to keep track of what’s happening, and the publishers are doing their job in trying to promote their composers, there’s only so much one musician can do and it does grow with age, actually it gets smaller, one’s capacity.

I suppose the idea of Brett Dean being composer in residence this season means there’s more connection with one figure.

Yes, it’s very welcome. That’s a wonderful opportunity for us as well as for him actually to get working with the same musicians.

So there’s nothing you particularly want to do?

I don’t have anything in my mind just now.

You’re so focused on the Nielsen.

Yes, it’s quite hard.

These are very tough programmes.

They are. Getting tougher and tougher, actually. This one’s relatively easy but the next three [starting with Wednesday night's concert] are really, really hard.

Add comment