The Dream of Gerontius, LPO, Elder, Royal Festival Hall | reviews, news & interviews

The Dream of Gerontius, LPO, Elder, Royal Festival Hall

The Dream of Gerontius, LPO, Elder, Royal Festival Hall

Elgar's oratorio at its Wagnerian finest under Elder

We’re still in the foothills of the Southbank Centre’s year-long The Rest is Noise festival, but already the harmonic ground is becoming unsteady underfoot. Last weekend saw the gemütlichkeit of Johann Strauss give way to the brutality of Richard Strauss, exposed us to the moistly chromatic flesh of Salome that lies behind the seven veils, and showed just a hint of Schoenbergian ankle.

Not exactly. Although latterly exorcised of its dangerous Catholic subversion and colonised by choral middle-England, there is much in this astonishing oratorio to thrill. Framing it in the context of Strauss (who, incidentally, hailed Elgar as “the first English progressivist” after hearing the Gerontius) allows the work’s Wagnerian structural conception and harmonic richness to emerge, rather than swaddling its challenges in the cotton-wool of musical Englishness.

Elder’s grasp of the work’s internal geography is absolute

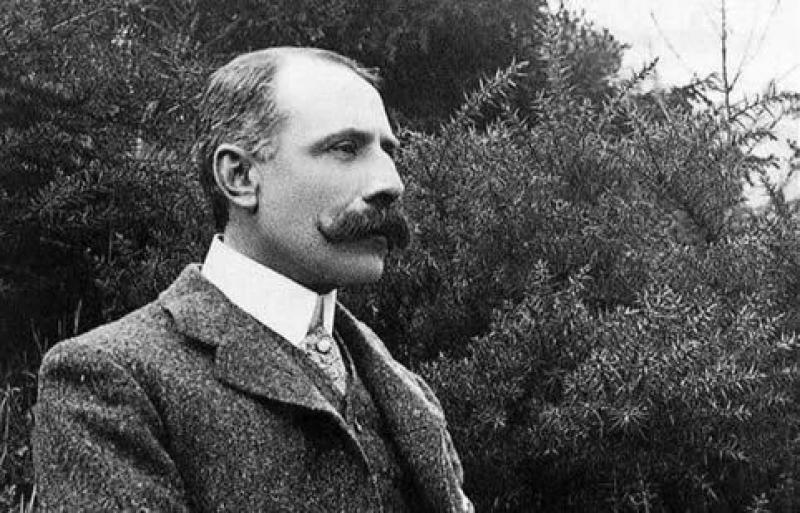

Mark Elder (pictured below) is one of the finest Elgarians, and over the past few years we’ve seen a glorious oratorio-cycle from him. But while The Apostles and The Kingdom have their moments, it is Gerontius that stands alone as a true masterwork. Helping him realise it here were the massed forces of the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir, with the Choir of Clare College, Cambridge serving as spiritual semi-chorus. Impeccably drilled, the chorus were admirable in their restraint, allowing themselves little more than a mezzo-piano for much of the evening. If moments of Cardinal Newman’s text were lost as a result, it was all worth it is the sonic payoff of their release (together with the full might of the LPO’s brass and percussion) at climactic moments.

The oratorio’s two movements replace conventional narrative with philosophical dialogue and contemplation, and so rely absolutely on the musical pacing if the Soul’s journey isn’t to lack direction. Elder’s tempos are by no means swift, but his grasp of the work’s internal geography is absolute, allowing things to be spacious without ever feeling stagnant. The hesitant doubt of the work’s opening in wind and low strings returns strangely transmogrified in the high-string melody of Part II – a relationship Elder’s direction renders organic and inevitable.

The oratorio’s two movements replace conventional narrative with philosophical dialogue and contemplation, and so rely absolutely on the musical pacing if the Soul’s journey isn’t to lack direction. Elder’s tempos are by no means swift, but his grasp of the work’s internal geography is absolute, allowing things to be spacious without ever feeling stagnant. The hesitant doubt of the work’s opening in wind and low strings returns strangely transmogrified in the high-string melody of Part II – a relationship Elder’s direction renders organic and inevitable.

Only in moments of transition did the LPO falter, hinting perhaps at a lack of rehearsal time with the soloists. Tenor Paul Groves gives such a flexible reading of Gerontius, and it would have been nice to see the orchestra follow him more readily, rather than taking two bars each time to settle into the new tempo.

Groves’ operatic, dramatised wanderer sat well against the warm control of Sarah Connolly (pictured left). If there’s a better Angel singing today, I have yet to hear them. Church-pure and Wagner-large by turns, Connolly’s “Alleluia” is a prayer that would move the sternest God, thrumming as the emotional pulse of the performance.

Groves’ operatic, dramatised wanderer sat well against the warm control of Sarah Connolly (pictured left). If there’s a better Angel singing today, I have yet to hear them. Church-pure and Wagner-large by turns, Connolly’s “Alleluia” is a prayer that would move the sternest God, thrumming as the emotional pulse of the performance.

With the advertised Brindley Sherratt ill, James Rutherford stepped in to provide stentorian support as the Priest. He added a darker colour to the gentler shades of Clare Choir and the London Philharmonic Choir, whose tone is never less than lovely, but who never quite seemed to find the darkest shades of Elgar’s demonic writing, the “uncouth dissonance” Newman’s text speaks of so vividly.

Next weekend with see The Rest is Noise delving into musical nationalism, allowing Englishness a more expansive voice. But it feels right, natural that Gerontius should be set apart. It’s a work that sees Elgar not just at his finest but at his most Germanic. It will always be a national treasure, but in the composer’s conception and Elder’s generous interpretation Elgar’s oratorio is surely an international treasure too.

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Faust, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Nelsons review - grace, then grandeur

A great fiddler lightens a dense orchestral palette

BBC Proms: Faust, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Nelsons review - grace, then grandeur

A great fiddler lightens a dense orchestral palette

BBC Proms: Jansen, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - confirming a phenomenon

Second Prom of a great orchestra and chief conductor in waiting never puts a foot wrong

BBC Proms: Jansen, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - confirming a phenomenon

Second Prom of a great orchestra and chief conductor in waiting never puts a foot wrong

BBC Proms: Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - defiantly introverted Mahler 5 gives food for thought

Chief Conductor in Waiting has supple, nuanced chemistry with a great orchestra

BBC Proms: Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - defiantly introverted Mahler 5 gives food for thought

Chief Conductor in Waiting has supple, nuanced chemistry with a great orchestra

Dunedin Consort, Butt / D’Angelo, Muñoz, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tedious Handel, directionless song recital

Ho-hum 'comic' cantata, and a song recital needing more than a beautiful voice

Dunedin Consort, Butt / D’Angelo, Muñoz, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tedious Handel, directionless song recital

Ho-hum 'comic' cantata, and a song recital needing more than a beautiful voice

Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress

This year's big anniversary celebrated with a pair of boxes, plus clarinets, pianos and sacred music

Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress

This year's big anniversary celebrated with a pair of boxes, plus clarinets, pianos and sacred music

BBC Proms: Liu, Philharmonia, Rouvali review - fine-tuned Tchaikovsky epic

Sounds perfectly finessed in a colourful cornucopia

BBC Proms: Liu, Philharmonia, Rouvali review - fine-tuned Tchaikovsky epic

Sounds perfectly finessed in a colourful cornucopia

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: A Mass of Life, BBCSO, Elder review - a subtle guide to Delius's Nietzschean masterpiece

Mark Elder held back from blasting the audience with a wall of sound

BBC Proms: A Mass of Life, BBCSO, Elder review - a subtle guide to Delius's Nietzschean masterpiece

Mark Elder held back from blasting the audience with a wall of sound

BBC Proms: Le Concert Spirituel, Niquet review - super-sized polyphonic rarities

Monumental works don't quite make for monumental sounds in the Royal Albert Hall

BBC Proms: Le Concert Spirituel, Niquet review - super-sized polyphonic rarities

Monumental works don't quite make for monumental sounds in the Royal Albert Hall

Frang, Romaniw, Liverman, LSO, Pappano, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - sunlight, salt spray, Sea Symphony

Full force of the midday sea in the Usher Hall, thanks to the best captain at the helm

Frang, Romaniw, Liverman, LSO, Pappano, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - sunlight, salt spray, Sea Symphony

Full force of the midday sea in the Usher Hall, thanks to the best captain at the helm

Elschenbroich, Grynyuk / Fibonacci Quartet, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mahogany Brahms and explosive Janáček

String partnerships demonstrate brilliant listening as well as first rate playing

Elschenbroich, Grynyuk / Fibonacci Quartet, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mahogany Brahms and explosive Janáček

String partnerships demonstrate brilliant listening as well as first rate playing

Comments

What on earth is meant by the

LPO Chorus=LPO Choir.

I think it's really just good

Apologies for the lapse - the

Apologies for the lapse - the London Philharmonic Choir has now been restored to its correct title. Alexandra

Thank-you, it's very much