Caspar Henderson: A Book of Noises - Notes on the Auraculous review - a call to ears | reviews, news & interviews

Caspar Henderson: A Book of Noises - Notes on the Auraculous review - a call to ears

Caspar Henderson: A Book of Noises - Notes on the Auraculous review - a call to ears

A new paean to a miraculously noisy world

Have you ever considered the sheer range of sounds? You may think of deliberate human efforts to move the air: music and song, poetry or baby talk, cries and whispers. Other human-made noises come to mind: sirens, bells, fireworks; the hum of the street or the bustle of an army on the move. Animal and bird sounds appeal, of course, along with the music of a landscape – creaking branches, tinkling streams, or whistling winds.

Henderson’s appetite for marvellous phenomena, and commitment to searching them out, makes him a most congenial literary companion. He demonstrated that amply in his Book of Barely Imagined Beings on the byways of natural history, and A New Map of Wonders, which ranged more widely over things to appreciate about the world. Sometimes, he wrote in that book, the mere act of noticing can bring about a state approaching enlightenment.

In this latest, more modestly titled volume, he is helping us to notice sound or noise – he uses the words interchangeably – and perhaps to listen more deeply. It’s loosely organised around four categories of sound, beginning with those (metaphorical) cosmic sounds. After the music of the heavens he moves on to sounds of the Earth (“geophony”), sounds of living things, and – the longest section – sounds we make. Each section is a set of free-standing mini-essays, which are suggestive rather than comprehensive, so it is a book for dipping into rather than a reviewer’s orderly inspection from first page to last.

Diving in, one brings up something unexpected from almost every page. The appeal of a grand miscellany like this depends on the industry and good taste of the compiler, and Henderson is reliable on both counts, as intriguing as he is eclectic. Try the index entries for “K”, which range over kangaroos and Kandinsky; katydids and Athanasius Kircher; klezmer and Krakatoa; krill, Krishna, koras, and Keats.

Diving in, one brings up something unexpected from almost every page. The appeal of a grand miscellany like this depends on the industry and good taste of the compiler, and Henderson is reliable on both counts, as intriguing as he is eclectic. Try the index entries for “K”, which range over kangaroos and Kandinsky; katydids and Athanasius Kircher; klezmer and Krakatoa; krill, Krishna, koras, and Keats.

It’s not a book that lends itself to summary, and readers will come away struck by different items in the glittering array here. Henderson offers them up with just enough commentary to leave you wanting more, putting each briefly in context, describing them vividly, and making liberal use of well-chosen quotations from a large collection of other writers. My favourites at the moment include the single picometre (that’s one million, millionth of a metre) my eardum needs to move to register the faintest audible sound; the fact that the Northern Lights make a sound (a soft crackling); and the astonishing evolutionary arms race between bats that hunt by ultrasound echoes, and their moth prey that generate their own pulses to jam the bats’ signals, or grow scales that absorb the bats clicks instead of reflecting them back to the hunters. There are many, many more, but best to choose your own.

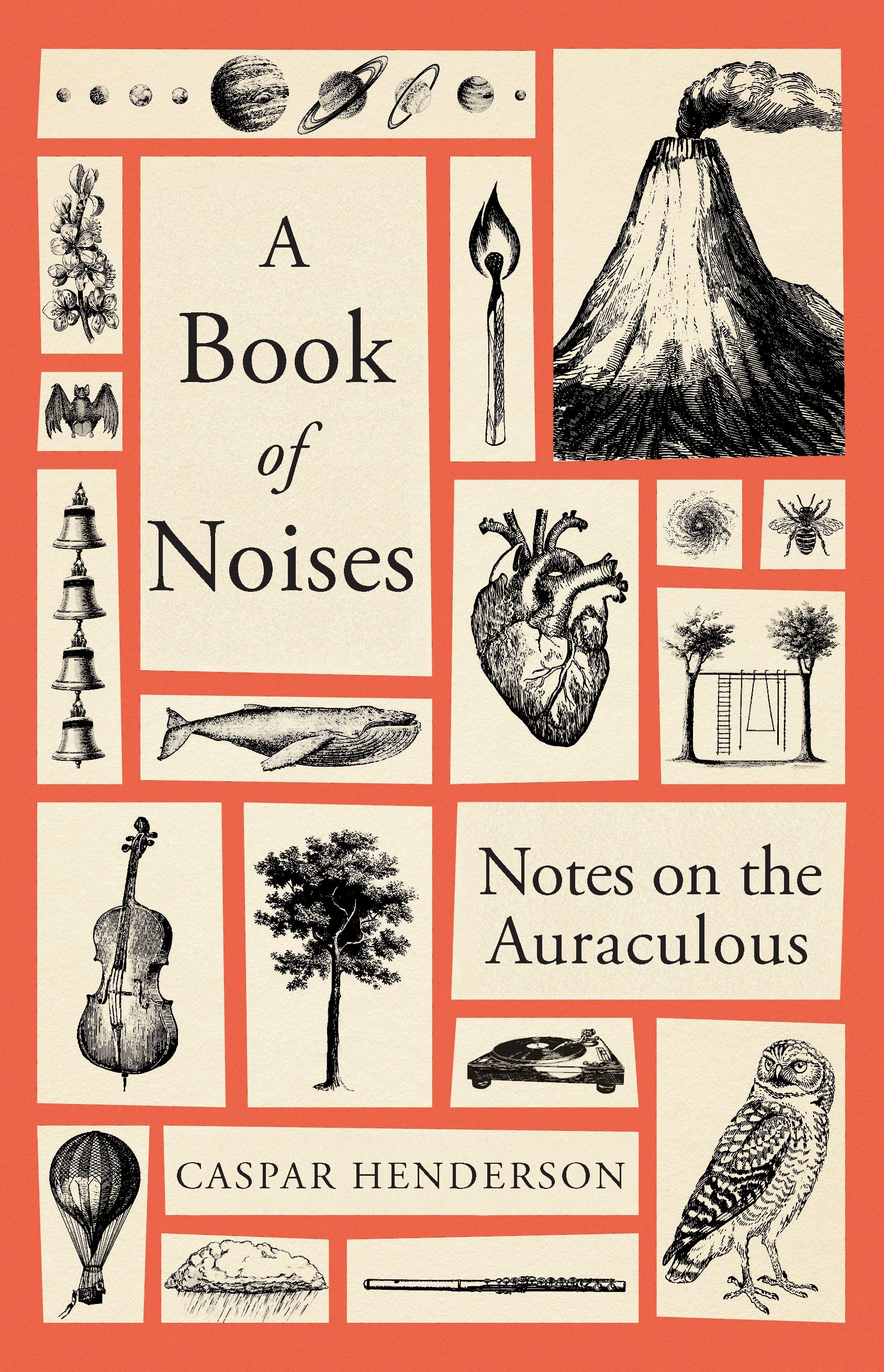

The other decision for the reader is how often to pause and search for the sound under discussion. Henderson’s previous two books were notable for beautiful illustrations, but a volume devoted to sound doesn’t lend itself to that. The links are not given, but a quick Google or a visit to YouTube complements the silence of a book. I recommend succumbing to that temptation. This is a book that could be read quickly, skipping and skimming. But a slower approach, seeking out the actual sounds and pondering them, aligns better with the author’s intent.

Like its predecessors, Henderson’s latest is a heartfelt extended plea to pay closer attention to the things around us, and a guide to the rewards that can come from doing that: a secular invitation to renew a sense of wonder, as a bulwark against the disenchantment of the world. Henderson has a proper sense of the perilous state of the planet, a recurrent side-topic in these pages, but he is typically of good cheer because, as he writes, he dwells in “a world alive with good noises”. They can’t all be squeezed into one book, but a marvellous selection of them is to be found here.

- A Book of Noises: Notes on the Auraculous by Caspar Henderson (Granta, £16.99)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Comments

The book is wonderful! I am

The book is wonderful! I am hoping for the revelation of the conclusion of the chapter "Thunder." Page 56 is blank....