Gloriana, Royal Opera | reviews, news & interviews

Gloriana, Royal Opera

Gloriana, Royal Opera

Affectionate pageant and private tragedy meet in Richard Jones's surefooted Tudorbethan Britten

Britten’s coronation opera, paying homage less to our own ambiguous queen than to the private-public tapestries of Verdi’s Aida and Don Carlo, is not the rarity publicity would have you believe, at least in its homeland. English National Opera successfully rehabilitated it in the 1980s, with Sarah Walker resplendent as regent. Phyllida Lloyd’s much revived Opera North production gave Josephine Barstow the role of a lifetime, enshrined in an amazing if selective film.

With Jones, though, it’s not a case of "either..or" but "both". His picture book fairy tales have a habit of turning the stomach and getting under the skin. Think of his Hänsel und Gretel, Anna Nicole, Pelléas et Mélisande: the list is endless but the productions never tell the same story. This one takes an institute pageant of 1953 – the director, incidentally, was born a day before the opera's world premiere that year – as both its starting point and its dramatically transfigured end, realised with such fantastical affection that there’s no hint of sarcastic parody. From before the first bars of music which Jones sets with such a careful ear to after the last, the staging is note perfect.

A local mayor takes the young queen to inspect the stage, a horde of little boys hold up word boards to set the scene, and we’re off – with a regal parade from Windsors back to Tudors immaculately choreographed to every bar of Britten’s tournament fanfares, sallies and tattoos. The lights sometimes blind us, as they did in Jones’s parallel Young Vic Ibsen staging. Everyone is perfectly introduced with am-dram gestures writ reassuringly large: the envious Earl of Essex (Toby Spence, back in top voice after a serious illness as the very best and fullest of Britten tenors), his rival for an hour Mountjoy (Mark Stone), supercilious Raleigh (forthright bass Clive Bayley) and good queen Bess whose every word is sycophantically approved by the chorus and who rides off with her reconciled bucks in a floral state coach (pictured above)

A local mayor takes the young queen to inspect the stage, a horde of little boys hold up word boards to set the scene, and we’re off – with a regal parade from Windsors back to Tudors immaculately choreographed to every bar of Britten’s tournament fanfares, sallies and tattoos. The lights sometimes blind us, as they did in Jones’s parallel Young Vic Ibsen staging. Everyone is perfectly introduced with am-dram gestures writ reassuringly large: the envious Earl of Essex (Toby Spence, back in top voice after a serious illness as the very best and fullest of Britten tenors), his rival for an hour Mountjoy (Mark Stone), supercilious Raleigh (forthright bass Clive Bayley) and good queen Bess whose every word is sycophantically approved by the chorus and who rides off with her reconciled bucks in a floral state coach (pictured above)

The other most rigidly formal public scene of the Royal Opera’s first half, the masque in Norwich, also passes with pleasant pomp. A giant vegetable display fits with the courtly theme of England’s fecundity; Britten’s potentially anodyne choral dances are complemented by Lucy Burge’s choreographic homage to an Ashton Pas de Deux. This is the "green" movement of Mimi Jordan Sherin’s lighting and Ultz’s gaudy designs, both of which are not so much painterly as symphonic, so fluidly do they move with Jones’s changes of inflection.

The other most rigidly formal public scene of the Royal Opera’s first half, the masque in Norwich, also passes with pleasant pomp. A giant vegetable display fits with the courtly theme of England’s fecundity; Britten’s potentially anodyne choral dances are complemented by Lucy Burge’s choreographic homage to an Ashton Pas de Deux. This is the "green" movement of Mimi Jordan Sherin’s lighting and Ultz’s gaudy designs, both of which are not so much painterly as symphonic, so fluidly do they move with Jones’s changes of inflection.

Between the ensembles, Susan Bullock’s Gloriana and Spence’s plaything champing at the bit (pictured left) move downstage for the limelight – which means in to the enchanted air of the Second Lute Song, transporting both into a private world. We’re not allowed to forget the convention of a harpist for the lute, placed “offstage” left just as later a player in the wings doubles a Ballad Seller’s gittern and antiphonal bell ringers mark the city crier’s proclamations. Balcony bands of trumpeters and woodwind are properly, and excitingly, part of the action.

Private and public begin to merge in the Whitehall ball scene, where professional dancers may leap highest in the Lavolta but the singers, Spence especially, are well up to their stylish level. Bullock’s Gloriana seems to be losing the plot as she ludicrously struts in Lady Essex’s stolen, ill-fitting finery.

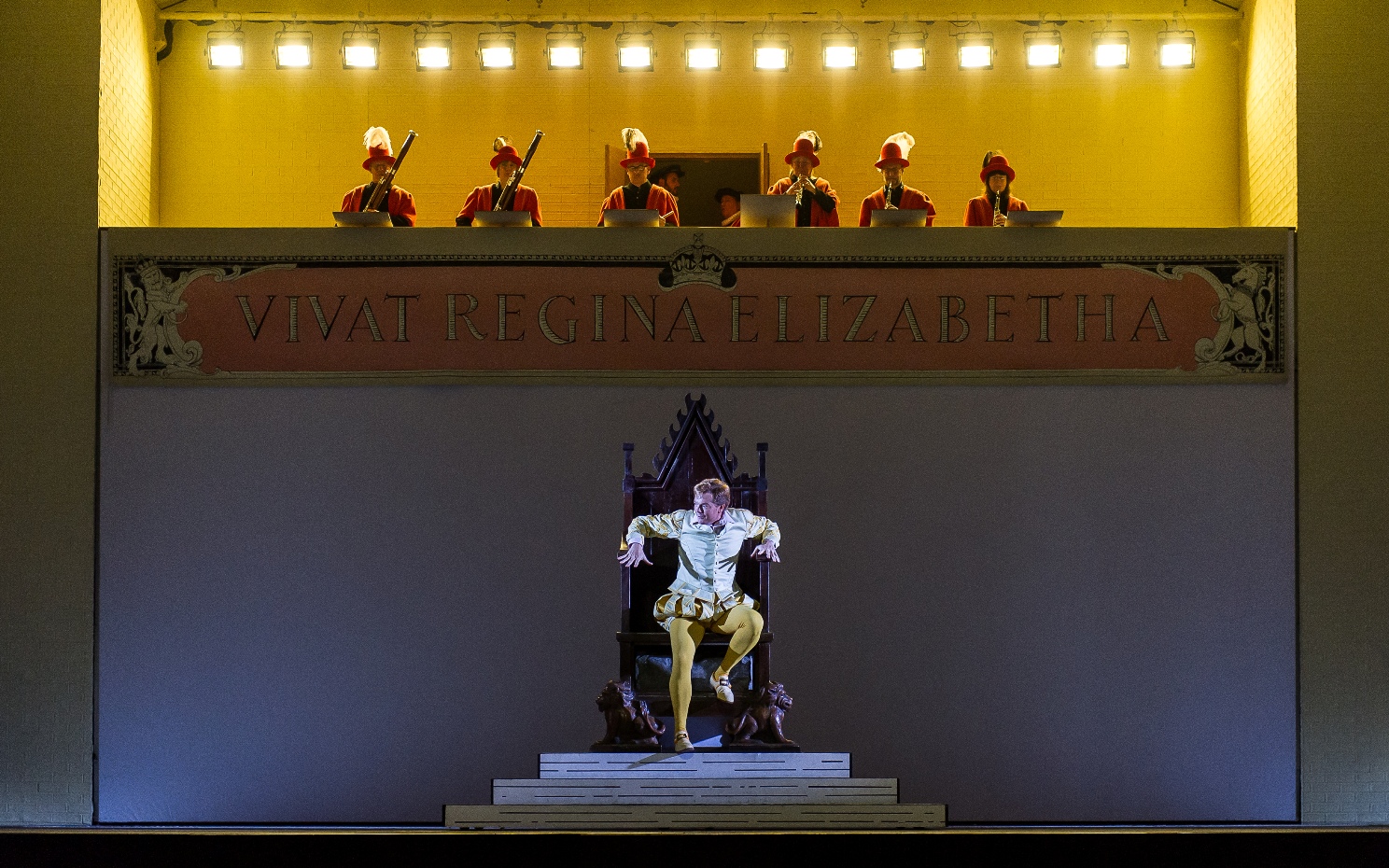

Britten tells us that the air has soured when Essex should be more wary of getting what he wants – the post of Lord Deputy to quell the Irish rebellion. A pall spreads upwards from Paul Daniel and the Royal Opera Orchestra, who always seem to have the perfect audience-stilling instincts for the moments of gravity (some of the more brilliant introductions still need a bit of ensemble work). Essex is left alone like a child dwarfed by the great throne of state (pictured above). It's a huge part of Spence's success in characterisation that his boyishness mitigates the rank ambition of the silly Earl.

Britten tells us that the air has soured when Essex should be more wary of getting what he wants – the post of Lord Deputy to quell the Irish rebellion. A pall spreads upwards from Paul Daniel and the Royal Opera Orchestra, who always seem to have the perfect audience-stilling instincts for the moments of gravity (some of the more brilliant introductions still need a bit of ensemble work). Essex is left alone like a child dwarfed by the great throne of state (pictured above). It's a huge part of Spence's success in characterisation that his boyishness mitigates the rank ambition of the silly Earl.

The auguries are good, then, for a Third Act which needs to grasp the nettle of Britten’s sudden seriousness as his Gloriana becomes a cross between duty-stricken Captain Vere in the previous masterpiece, Billy Budd, and the domineering Governess of the chamber opera still to come in the 1950s, The Turn of the Screw. The shock of the failed Essex’s intrusion on the queen without her wig (pictured above) is bound to kick start a new level of action. Bullock, up to this point only asked to be regal, stagily capricious and secure in ringing authority – which she is, with the exception of a slightly murky zone in the lower-middle register, toll of all those Brünnhildes she’s had to sing – ratchets up the intensity.

It’s now clear that the Queen is the one real person in the pageant, limping and pacing arthritically outside its neat boundaries. Britten’s sombrely scored echoes of the happier Act One duet are reinforced by identical stage positions - Essex now slumped rather than lute-strumming against the table as the tired Elizabeth takes up her place in front of the institute proscenium to admit total failure. We’re on the edge of our seats.

The show still goes on. Glimpses of stage management in the odd scene where a blind Ballad Singer, perfectly pitched a note below hammy by the refulgent Brindley Sherratt, describes the quick failure of Essex’s London rebellion keep this tricky intermezzo sharp and weird. Then all eyes are on the Queen’s dilemma.

The show still goes on. Glimpses of stage management in the odd scene where a blind Ballad Singer, perfectly pitched a note below hammy by the refulgent Brindley Sherratt, describes the quick failure of Essex’s London rebellion keep this tricky intermezzo sharp and weird. Then all eyes are on the Queen’s dilemma.

Male courtiers close in to persuade her to sign the rebel’s death warrant; humanity belongs to the women in the exchanges with Patricia Bardon’s stylish and sympathetic Lady Essex, whose pleas for her children (pictured left) re-engage the woman in Elizabeth, and Kate Royal’s not quite nervy-ambitious enough Penelope Rich, Essex's sister and Mountjoy's lover; for her to inflame the wavering regent, the battle of the high notes should be stronger than this. The men, though, are consistently strong, from baritone Jeremy Carpenter’s house debut as a suave Cecil to another Royal Opera novice, Britten tenor-in-waiting Andrew Tortise as the Spirit of the Masque.

Ultimately, though, all focus is on what Bullock can do with the final scene of the Queen’s fading (pictured right) after Essex’s execution, to the shattering full-orchestral reprise of the Second Lute Song. Her declamation of historical texts is impressive, her shrivelling to a worn-out spider in the corner of the giant throne riveting.

Ultimately, though, all focus is on what Bullock can do with the final scene of the Queen’s fading (pictured right) after Essex’s execution, to the shattering full-orchestral reprise of the Second Lute Song. Her declamation of historical texts is impressive, her shrivelling to a worn-out spider in the corner of the giant throne riveting.

Above all, hers is a committed homage to Britten’s unique and unchallenged operatic setting of the English language (even if, as many have been too keen to point out, librettist William Plomer was no Auden). The highest glory, though, as acknowledged by first-night applause far from the begloved, bewildered politeness of the Royal Opera audience 60 years ago, belongs to Jones and his production team, battening down the hatches on backstage reality as the music and the dying queen, absolutely alone, concede defeat. That the final silent tableau of the reassembled cast greeting Her youthful Madge comes as no fatuous symmetry but as something rich and strange is all part of this production’s special magic. On its own unique terms, it puts not a single foot wrong - the crowning glory, perhaps, of quite a week for mighty Britten.

- Five more performance of Gloriana at the Royal Opera until 6 July. The performance on Monday 24 June will be broadcast live into cinemas across the world; the performance on 29 June will be broadcast on BBC Radio 3

- Read more about the background of Gloriana on David Nice's blog

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Comments

where is the review of the

Since you clearly found

Since you clearly found reading the whole long piece a bore, or maybe you didn't turn the page, I've extracted the relevant passages for your benefit, excluding a few adjectival words of praise for Bayley and Sherratt:

'Bullock, up to this point only asked to be regal, stagily capricious and secure in ringing authority – which she is, with the exception of a slightly murky zone in the lower-middle register, toll of all those Brünnhildes she’s had to sing – ratchets up the intensity… Ultimately, though, all focus is on what Bullock can do with the final scene of the Queen’s fading after Essex’s execution, to the shattering full-orchestral reprise of the Second Lute Song. Her declamation of historical texts is impressive, her shrivelling to a worn-out spider in the corner of the giant throne riveting. Above all, hers is a committed homage to Britten’s unique and unchallenged operatic setting of the English language...

'Toby Spence, back in top voice after a serious illness as the very best and fullest of Britten tenors…It's a huge part of Spence's success in characterisation that his boyishness mitigates the rank ambition of the silly Earl...

'Humanity belongs to the women in the exchanges with Patricia Bardon’s stylish and sympathetic Lady Essex, whose pleas for her children re-engage the woman in Elizabeth, and Kate Royal’s not quite nervy-ambitious enough Penelope Rich, Essex's sister and Mountjoy's lover; for her to inflame the wavering regent, the battle of the high notes should be stronger than this. The men, though, are consistently strong, from baritone Jeremy Carpenter’s house debut as a suave Cecil to another Royal Opera novice, Britten tenor-in-waiting Andrew Tortise as the Spirit of the Masque.'