Reissue CDs Weekly: Marylebone Beat Girls, Milk of the Tree | reviews, news & interviews

Reissue CDs Weekly: Marylebone Beat Girls, Milk of the Tree

Reissue CDs Weekly: Marylebone Beat Girls, Milk of the Tree

From the mid-Sixties to the early Seventies, the shifting context of the female voice is chronicled

Between them, Marylebone Beat Girls and Milk of the Tree cover the years 1964 to 1973. Each collects tracks recorded by female singers: whether credited as solo acts, fronting a band or singer-songwriters performing self-penned material.

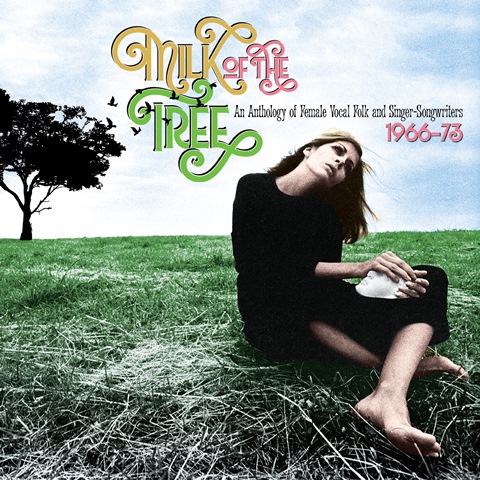

As that quote suggests, Milk of the Tree: An Anthology Of Female Vocal Folk & Singer-Songwriters 1966-1973 is the more agenda driven compilation of the two. Its promo material states “The feminist movement naturally coincided with the first signs of genuine [female] musical emancipation.” It is this liberation that Milk of the Tree seeks to get to grips with.

Instead of overtly grappling with socio-political concerns, Marylebone Beat Girls 1964-1967 straightforwardly collects 25 tracks issued on singles by the EMI group of labels – EMI was based in Marylebone, hence the title.

Instead of overtly grappling with socio-political concerns, Marylebone Beat Girls 1964-1967 straightforwardly collects 25 tracks issued on singles by the EMI group of labels – EMI was based in Marylebone, hence the title.

Taken together, both releases capture pop as it sprouted branches to be taken seriously: by songwriters and the listening audience. Of course, there is no reason why a Cilla Black B-side from 1964 shouldn’t be given the same consideration as a 1971Sandy Denny album track. Equally, even though backroom string-pullers and tinsel-bright pop never went away, the period saw radical changes in how, irrespective of gender, band members, singers and songwriters positioned themselves in response to The Beatles' and Bob Dylan's inherent self-definition.

On the all-British Marylebone Beat Girls, one track is written by the artist to whom the single is credited. Barbara Ruskin’s Turtles-ish 1967 single “Euston Station” is a yearning Ray Davies-style evocation using the bustle of the London rail terminus as a metaphor for never getting anywhere. Ruskin had entered the music business with the express intention of making her way as a songwriter and ended up recording her own songs in parallel with her publisher placing them with other performers. In early 1965, her first single featured one of her own compositions as its B-side. She was already a singer-songwriter.

Marylebone Beat Girls plays off songs from UK writers against covers of American material. Though everything collected is wonderful, a stand-out is Julie Driscoll’s (pictured below left) intense, swirling Dusty Springfield-esque 1967 single “I Know You Love me Not”. Written by Brian Godding of the band Blossom Toes, it was produced by their’s and Driscoll’s manager Giorgio Gomelsky. Another gem is Cilla Black’s 1964 B-side “”Suffer Now I Must”, the flip of “You’re my World”. Penned by her future husband Bobby Willis, it’s an irresistible Bacharach & David-influenced swinger.

Elsewhere, there are ripostes to the American girl-group sound, sass-filled Brit soul, pre-Beatle era singers getting to grips with the big beat (Alma Cogan’s “Love is a Word” is a stunner), dives into Phil Spector grandiosity and hard-edged rocker combos (The She Trinity’s rattling version of The Bobby Fuller Four’s “I Fought the Law”). Head for Helen Shapiro’s compelling and long-lauded dance-floor filler “Stop and You Will Become Aware” for instant proof of Marylebone Beat Girls’ indispensability.

Elsewhere, there are ripostes to the American girl-group sound, sass-filled Brit soul, pre-Beatle era singers getting to grips with the big beat (Alma Cogan’s “Love is a Word” is a stunner), dives into Phil Spector grandiosity and hard-edged rocker combos (The She Trinity’s rattling version of The Bobby Fuller Four’s “I Fought the Law”). Head for Helen Shapiro’s compelling and long-lauded dance-floor filler “Stop and You Will Become Aware” for instant proof of Marylebone Beat Girls’ indispensability.

Rather than a single CD, Milk of the Tree is a three-disc set in clamshell box. At four hours, with 60 tracks from the US and UK, and its professed agenda it is no minor release. Thankfully, the weightiness is leavened by being a great listen and, like Marylebone Beat Girls, free from clunkers. Where well-known names appear, care has been taken to include lesser-known but still representative tracks. Joan Armatrading’s 1972 album track “It Could Have Been Better” is heard: a reminder of her musical potency before the 1976 “Love and Affection” hit single. The seismically influential Laura Nyro’s entry is “Upstairs by a Chinese Lamp” from 1970’s Christmas and the Beads of Sweat album. Other star names include Mary Hopkin, Melanie, Buffy Sainte-Marie and Judee Sill. They sit alongside known quantities Susan Christie, Dana Gillespie, Bridget St. John and genuine obscurities like Hendrickson Road House and the duo Emily Muff. Joni Mitchell is not heard.

Some selections muddy the waters of Milk of the Tree as a showcase for self-expression. Though The Stone Poneys were fronted by Linda Ronstadt, “Different Drum” was written by Mike Nesmith. Nico’s Lou Reed/Sterling Morrison-composed “Chelsea Girls” was their perspective on the New York milieu rather than that of the singer singing the song.

A male presence is often near. Janis Ian’s “Society’s Child” was produced and arranged by Shadow Morton. Marianne Faithfull’s “Something Better” is a Gerry Goffin and Barry Mann song, arranged by Jack Nitzsche and produced by Mick Jagger. Ruthann Friedmann’s own “Windy”, heard here by her, is more familiar from the hit version by The Association. The same one-step-removed familiarity applies to Jackie DeShannon's “Come Stay With me” – here in the songwriter’s 1968 version. Initially, it was a 1965 single as interpreted by Marianne Faithfull.

A male presence is often near. Janis Ian’s “Society’s Child” was produced and arranged by Shadow Morton. Marianne Faithfull’s “Something Better” is a Gerry Goffin and Barry Mann song, arranged by Jack Nitzsche and produced by Mick Jagger. Ruthann Friedmann’s own “Windy”, heard here by her, is more familiar from the hit version by The Association. The same one-step-removed familiarity applies to Jackie DeShannon's “Come Stay With me” – here in the songwriter’s 1968 version. Initially, it was a 1965 single as interpreted by Marianne Faithfull.

While Milk of the Tree mixes its messages, the music collected is uniformly superb. From (just-about) straight folk, through recognisably singer-songwriter fare to individualists like Anne Briggs, Vashti Bunyan and Mandy More (whose extraordinary “If Not by Fire” has to headed to immediately), it is a flawless listen. Nonetheless, questions of viewpoints are raised.

Does the era charted by Milk of the Tree require a single-gender focus? Could this story be told within the frame of a wider context? Both questions resonate more broadly. In 2008, the Norwegian singer-songwriter Susanne Sundfør said "first and foremost I am an artist, not first and foremost a woman" on being awarded the Spellemannprisen – the Norwegian Grammy – for Female Artist of the Year. In 2010, when she was nominated in the Spellemannprisen’s gender-defined strands, she withdrew from those categories. The point was taken and, as a result, the Spellemannprisen no longer makes its awards on a gender basis.

Sundfør is not unique in having such thoughts. Recently, Gaye Advert, bassist with punk band The Adverts, said of her time with them “I never wanted to be a female in a band, I just wanted to be a bass player”. Though Marylebone Beat Girls’ liner notes do not say so, it’s a fair bet Barbara Ruskin similarly saw herself as a songwriter rather than a female songwriter. Male soul-pop band The Foundations recorded her “Hold me Just a Little While Longer”. Not thinking about gender has its place.

- Next week: the whopping Fairport Convention box set Come All Ye - The First 10 Years

- Read more reissue reviews on theartsdesk

Buy

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Trio Da Kali, Milton Court review - Mali masters make the ancient new

Three supreme musicians from Bamako in transcendent mood

Trio Da Kali, Milton Court review - Mali masters make the ancient new

Three supreme musicians from Bamako in transcendent mood

Hollie Cook's 'Shy Girl' isn't heavyweight but has a summery reggae lilt

Tropical-tinted downtempo pop that's likeable if uneventful

Hollie Cook's 'Shy Girl' isn't heavyweight but has a summery reggae lilt

Tropical-tinted downtempo pop that's likeable if uneventful

Pop Will Eat Itself's 'Delete Everything' is noisy but patchy

Despite unlovely production, the Eighties/Nineties unit retain rowdy ebullience

Pop Will Eat Itself's 'Delete Everything' is noisy but patchy

Despite unlovely production, the Eighties/Nineties unit retain rowdy ebullience

Music Reissues Weekly: The Earlies - These Were The Earlies

Lancashire and Texas unite to fashion a 2004 landmark of modern psychedelia

Music Reissues Weekly: The Earlies - These Were The Earlies

Lancashire and Texas unite to fashion a 2004 landmark of modern psychedelia

Odd times and clunking lines in 'The Life of a Showgirl' for Taylor Swift

A record this weird should be more interesting, surely

Odd times and clunking lines in 'The Life of a Showgirl' for Taylor Swift

A record this weird should be more interesting, surely

Waylon Jennings' 'Songbird' raises this country great from the grave

The first of a trove of posthumous recordings from the 1970s and early 1980s

Waylon Jennings' 'Songbird' raises this country great from the grave

The first of a trove of posthumous recordings from the 1970s and early 1980s

Lady Gaga, The Mayhem Ball, O2 review - epic, eye-boggling and full of spirit

One of the year's most anticipated tours lives up to the hype

Lady Gaga, The Mayhem Ball, O2 review - epic, eye-boggling and full of spirit

One of the year's most anticipated tours lives up to the hype

Slovenian avant-folk outfit Širom’s 'In the Wind of Night, Hard-Fallen Incantations Whisper' opens the door to inner space

Unconventional folk-based music which sounds like nothing else

Slovenian avant-folk outfit Širom’s 'In the Wind of Night, Hard-Fallen Incantations Whisper' opens the door to inner space

Unconventional folk-based music which sounds like nothing else

'The Art of Loving': Olivia Dean's vulnerable and intimate second album

Neo soul Londoner's new release outgrows her debut

'The Art of Loving': Olivia Dean's vulnerable and intimate second album

Neo soul Londoner's new release outgrows her debut

Music Reissues Weekly: The Peanut Butter Conspiracy - The Most Up Till Now

Definitive box-set celebration of the Sixties California hippie-pop band

Music Reissues Weekly: The Peanut Butter Conspiracy - The Most Up Till Now

Definitive box-set celebration of the Sixties California hippie-pop band

Doja Cat's 'Vie' starts well but soon tails off

While it contains a few goodies, much of the US star's latest album lacks oomph

Doja Cat's 'Vie' starts well but soon tails off

While it contains a few goodies, much of the US star's latest album lacks oomph

Comments

Laura Nyro's 1968 LP 'Eli and