Philip Seymour Hoffman, Best Character Actor | reviews, news & interviews

Philip Seymour Hoffman, Best Character Actor

Philip Seymour Hoffman, Best Character Actor

The great American actor has died aged 46. theartsdesk pays tribute with a major Q&A

The news that Philip Seymour Hoffman has died at the age of only 46 robs cinema of - almost unarguably - the greatest screen actor of the age, and certainly its outstanding character actor. Where once there was Charles Laughton, or Ernest Borgnine, for the past two decades there has been Philip Seymour Hoffman. They are all great film actors whom fate has fashioned in doughy clumps of misshapen flesh.

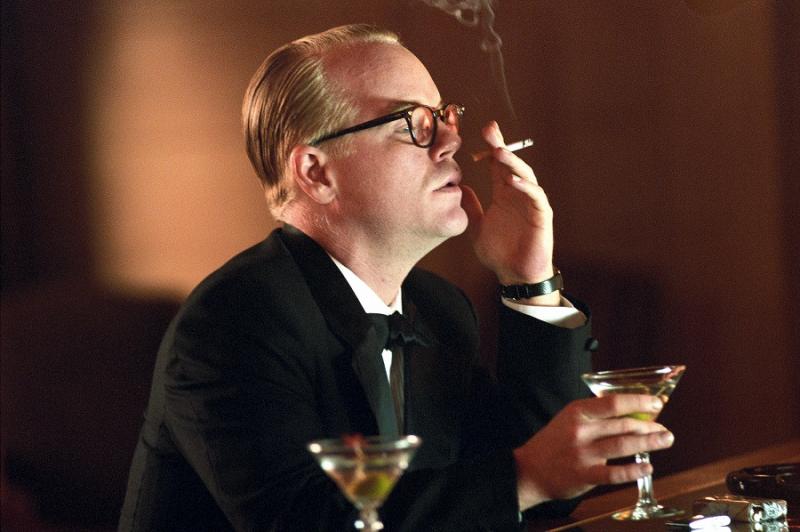

It is a sign of the era that Hoffman graced that not only did he never get the girl, he didn't get the guy either. See his Oscar-winning turn in Capote, or Boogie Nights, in both of which he moons after unobtainable males. His daring quest for roles outside cinema's norms, and an insistence on disappearing entirely inside the character, will be his defining legacy.

His name on the poster – the Seymour was added in when he started out as American Equity had another Philip Hoffman – was always a kitemark you could trust. The accidental star was in fewer dreadful films than perhaps any star on earth. No matter the size of the role - a barfly with one scene in Ricky Gervais's The Invention of Lying or a domineering cult leader in The Master, his fourth collaboration with Paul Thomas Anderson - his commitment to believability could be guaranteed. His reputation rests on going the extra mile. Need an actor to embody a weirdo, dropout, loser, freak, a pre-op transsexual, cold-call sex abuser? Dial Hoffman. His otherness lit up many era-defining films: Boogie Nights, Happiness, The Talented Mr Ripley, Magnolia, The Big Lebowski, Punch-Drunk Love.

His name on the poster – the Seymour was added in when he started out as American Equity had another Philip Hoffman – was always a kitemark you could trust. The accidental star was in fewer dreadful films than perhaps any star on earth. No matter the size of the role - a barfly with one scene in Ricky Gervais's The Invention of Lying or a domineering cult leader in The Master, his fourth collaboration with Paul Thomas Anderson - his commitment to believability could be guaranteed. His reputation rests on going the extra mile. Need an actor to embody a weirdo, dropout, loser, freak, a pre-op transsexual, cold-call sex abuser? Dial Hoffman. His otherness lit up many era-defining films: Boogie Nights, Happiness, The Talented Mr Ripley, Magnolia, The Big Lebowski, Punch-Drunk Love.

In his more recent appearances he was tending towards a middle ground of all-American normality. In George Clooney’s The Ides of March, he was an idealist among dastardly schemers on the Democrat campaign trail. In Moneyball, he played the doughty coach to a team of baseball misfits quixotically hired by Brad Pitt. In A Late Quartet he impersonated a top-flight violinist (and learned the instrument to be able to fake it.) Nor was he averse to lending ballast to Hollywood fantasy - Hunger Games, Mission Impossible III.

And then there was Jack Goes Boating. It probably won't be remembered alongside his greatest work - in an oddball romance he played a dreadlocked, reggae-obsessed limo-driving loner who miraculously did get the girl after all. What marks it out is that this was his directorial debut and it subtly suggested a promising future behind the camera to go with the mighty presence in front of it.

I interviewed Philip Seymour Hoffman three times: when he was directing a play for his company LAByrinth at the Donmar Warehouse in 2002, then when Jack Goes Boating and A Late Quartet were opening in the UK. He was entirely without fuss or airs and was hugely personable. That quality came through even when he portrayed characters at the extremes of the spectrum. “Even if I was hired into a leading-man part," he told me, "I’d probably turn it into the non-leading-man part.” Those interviews have been edited together into a Q&A which amounts to a kind of biography. And sadly, also a last word.

JASPER REES: Is there a role where you feel you took shape as an actor?

PHILIP SEYMOUR HOFFMAN: It’s a tricky question because I can relate back to when I was very young doing something in college or something where I had a moment where I was like “oh”, where I can say that moment was the defining moment. I’m not thinking of anything specific. I just know that I had experiences when I was young starting out trying to get going, that I had days and moments where really of a sudden something clicked. It’s more a conversation you’re having with yourself and you realise, "Ah, I can create something, I can do this, there’s something I can do with this, this isn’t just some willy-nilly, you know, silly thing. This is an actual craft, this is an art form, I can create something that can mean something." You have that experience that I can actually do that and that does something to you. That does shape you and define you. So to me that question is not so much connected to work so much as me being an actor and an artist. I think that happened when I was pretty young, when I was in college in my early twenties. I had enough of those experiences that kept me going. If I didn’t have any of those I probably would have stopped.

Did the circumstances of your childhood condition in you a desire to act?

I don’t know. That’s really too complicated a question to answer. I know that when I was 11 or 12 I was taken to the theatre. That’s really what it is. I was an athlete. I wasn’t bad. I grew up in a strongly competitive athletic town. I was good at baseball. Baseball I did well at. I was a wrestler too and I injured myself wrestling. Beginning of high school. And that was it. I was a pretty good hitter. It’s a great sport. In my mid teens that’s what I thought I’d do. Play sports and maybe study biology. But my mum took me to the theatre since I was 11, 12. I really really loved it there. I didn’t go to New York till I got out of high school. The first play I ever saw was All My Sons, so I saw a lot of sophisticated theatre for a young guy. I really loved it, so when I got hurt and I wasn't going to wrestle any more or play football I went out for this play and I ended up going to college for it.

Still it was not until I was sophomore junior year at college that it really became a strong passion of mine, when I was 20, 21. I think I was very passionate about watching it as a kid. It was a secret of mine. At that young age I don’t think I had the words to describe it but the feeling I had when I first saw a play was very corny. It was a miracle, it was magic. I couldn’t believe it. I was young and I remember I sat there and I couldn’t believe that people were making me believe something in front of my eyes. It was something that didn’t make any sense to me and so therefore amazing. And so I always had this thrill associated with it. I think that’s why. It’s something that stuck with me. By the time I became impassioned by it it was probably to recapture that feeling. When theatre does it there’s nothing better.

I got out of college. I never thought I’d be in a movie. It really wasn’t on the radar. I got into some summer theatre after college and did a play in New York and my manager saw it. I was 22. She took me on. I kept doing my no-money theatre gigs for the next couple of years but she started sending me out on film auditions. When I was 24 I got Scent of a Woman (pictured above) and there you go.

I got out of college. I never thought I’d be in a movie. It really wasn’t on the radar. I got into some summer theatre after college and did a play in New York and my manager saw it. I was 22. She took me on. I kept doing my no-money theatre gigs for the next couple of years but she started sending me out on film auditions. When I was 24 I got Scent of a Woman (pictured above) and there you go.

Were you a fan of the movies?

I wasn’t a big movie kid. I watched a lot of movies but it wasn’t till I got to college that my friends started going, “You haven’t seen Clockwork Orange?” I hadn’t seen anything.

Why hadn’t you?

My mum watched a tonne. But I went to college with all these cinephiles and you could go to the library or rent these movies and watch them.

So why can you act? Where does the empathy come from?

You have kids? Well, then you know. I have kids. Within eight months they’re so much who they’re going to be. My girlfriend [makeup artist Mimi O'Donnell] tells me that all the time. I mean they’re so incredibly unique and so vastly different from each other at a very young age. What Mimi and I do to them or act upon them as parents is definitely forming them in some way but, man, who they are is much more powerful. And you see. So again I would say I don't know if it has to do with the environment I grew up in or has a little bit to do with what I was born with or the personality that I came out of my mother with. I don’t know. But I think it’s a little bit of both. But I do think it has a lot to do with going to the theatre and going, "Oh I like that." Because I have to tell you I’m still more a fan of watching than actually doing.

You’ve directed theatre before, including twice in London. Jack Goes Boating finds you acting and directing at the same time. What brought that on?

You’ve directed theatre before, including twice in London. Jack Goes Boating finds you acting and directing at the same time. What brought that on?

I didn’t even think of making a film. This was Big Beach’s idea. They came and saw the play and they wanted to make it into a film and they came to us and John Ortiz said, "Why don't you direct it?" I directed a lot of plays with LAByrinth. I had to think about it for a couple of weeks and then I realised I started seeing it and then there was something with the story that I wanted to do. It wasn’t Jack that drew me to making the film; it was the dynamic of the two men and the couple. Those were the storylines that I actually keyed into as a director.

How did you find the business of doubling up?

When you’re acting it’s an inside job you can share with other actors. But if you’re directing and acting you’re on both sides of that equation so everyone’s just waiting on you completely which is ... it needs to be shared, that relationship. There needs to be an actor and a director and they should be sharing the responsibility of getting it right. I didn’t much like that feeling where I knew I wasn’t doing well. I had to help myself somehow. I had the writer and the director and the DoP but ultimately they can only help so much because ultimately I was going to make the final decision about whether to move on or not. In those moments I remember going, “Phil, remember this, remember this feeling right now. Don't do this again.” What you really have to do is get over yourself. Get over it, you have a job to do, move on. And I did. But in that moment I remember feeling it’s too much attention, it’s too many people just waiting on you. I like sharing it more.

All interviews with you tend to sound the same note: Philip Seymour Hoffman plays freaks and weirdos. And yet here you are playing the ultimate American everyman.

It’s weird. In my career I definitely have played some characters who are living on the extremes of their emotions or their experience. But I think I’ve played just as many parts that aren’t. Or they’re playing on the extremes in the opposite way of macho and instilling fear in others and those kinds of things. But I think people really identify with the people that are helpless. I really do. I think people remember those characters, because it speaks to something deep inside their own id. And they can’t shake it. The confident, the virile, that’s more of a fantasy to those people. Confidence I don’t think is a thing we just live with all the time. I think we more live with anxiety and fear about things than confidence about things. It’s the fantasy of things. I think that’s why people remember those parts a lot.

Jack goes swimming

The phrase often used of you – character actor. Are you our guy on the inside in the movies? Film stars don’t normally look like you.

I hope so. I hope that the representation of life is one that is truer or nears the experience of what other people experience of see around them. It is to me. Most people that I know as actors aren’t really in shape. You can see the weight of life on them pretty vividly, especially the get-up-and-work-10-hours-a-day people. And they don’t have the time to eat exactly what they want to eat, they don't have the time for the trainer, they don’t have the money for these things. And that is their life. So physically you’re not going to look that way all the time. And they’re not always going to have the hot girlfriend. A lot of them are going to be alone.

Jack Goes Boating is partly a portrayal of a broken marriage. Without wishing to make too ungainly or naff a segue, did the breakup of your parents' marriage resonate at all?

I don’t think that’s naff. I might even have said that at one point. It’s not that he’s me as a child. I know it’s not literal but I’m sure my experience of growing up and having parents that split up played into my understanding and that’s what I wanted to do with the story. If I say, “I love you, I’ll be with you,” the risk I’m taking is that you can destroy me. That really is life, everyone does know that deep down inside that when you really really get involved with someone on a level that’s that intense, then you’re giving them the power to hurt you that’s something like what you see in that scene. I remember that definitely has to do with knowing as a child when you watch that happen with your parents or just adults. Those are the things you remember. They play into "how am I going to go about navigating that world as an adult?"

If someone had said to you at 21, you'll win an Oscar ...

I probably would have laughed uncomfortably and not known why they’d said that. I didn't know I was going to be in films at that age. I thought I was going to do plays.

Since Capote have you been trying to regain your anonymity?

Yeah I think so. I think that’s fair to say. Not regain it but I’ve been trying to live the kind of life I had before. But it is different. But I’m still not that kind of celebrity where I’m hounded. There’s not many places I can go where I’m not recognised in life now.

Anthony Mingella [who directed Hoffman in The Talented Mr Ripley] said, “He is cursed by his own gnawing intelligence, his own discomfort with acting.”

[laughs]. I’m laughing again at Anthony. Anthony knew me and yeah, I think that acting is a love-hate thing, I think for sure. But I think when I worked with him it was even more so. But that was a great relationship.

Here’s another: “Capote had something I didn't have.”

I said that?

I think it was to do with fearlessness.

Yeah! I think that’s true. That was something that was very hard to get for that.

Was it fearlessness or shamelessness?

Yeah, it’s kind of walking into a room and saying, “I’m interesting.”

Watch the trailer to Capote

Did you ever see Toby Jones’s performance [as Capote in Notorious]?

I haven’t seen that, no. I haven’t seen it because when the films came out there was so much talk and drama around it that I remember I didn't want to see it because I didn't want to give any food it. I didn’t want to have an opinion about it because I didn’t want to see anything that would create any more stir about it. Then that passed and now it’s just seeing it. I do think I will. I also think that the idea of watching the story of Truman Capote again – it’s something I spent three years of my life doing. I put it down. When that film finished, how securely I put that part down I can’t even tell you. I really nailed that thing to the board and said, “Do not follow me ever again and closed the door.” You know what I mean? It’s not something at the forefront of my mind.

You don’t leave much trace of previous role in next one. Is that your goal?

I remember Meryl Streep said something once. "When they write a part for a middle-aged woman from New Jersey, I’ll play myself." I thought that was really smart.

Who is closest to yourself?

I think it’s really healthy sometimes to play people that have similar habits to you because that not an easy thing to do either. There’s aspects of everything that I’ve played that is me, for sure. It’s always you. But it’s just how you manipulate. I just did this part in this film my brother [Gordy Hoffman] wrote called Love Liza. He won best screenwriter at Sundance there. That probably is the closest to who I am. He was a website designer guy, I thought he probably doesn’t dress much differently than me and probably doesn’t behave and then I just let myself go. That’s the first time I’ve watched a film where it’s actually just me existing up there. It’s a tough watch because of that. There’s nothing between you and that character.

Watch the trailer to Love Liza

Do you seek variety?

Variety keeps things interesting, no doubt. But truly what anybody would be looking for - a good story. Something that’s easily pertinent to today in some shape, way or form. Even if it doesn't literally link up to today, you just have a sense that this would be a good thing to do right now, not just in my life but in the way the world is and stuff. I try to pick things more like that. Then down the tier of priorities is something like, well, is it a character you’ve played before? And I’ll look at that. And if it’s something that I think I’ve hit a couple of times already I won’t again, but sometimes I go through periods that are almost thematic where a year and a half or a couple of years I’ll almost be hitting the same issue. And then I’ll get sick of it.

When I did Boogie Nights (pictured) and Happiness and Flawless I was dealing with people who have extraordinary problems with intimacy, but not just guys who are having a problem with their girlfriend. Social intimacy problems, people who are literally socially malfunctioning through whatever reason and I found that very interesting. Those parts are extraordinarily different people but they operating pretty much in the same thematic ball park, people struggling with being a misfit socially but in grave need of intimacy. And I just found that very interesting. I think it’s a human dilemma, period, but because those stories deal with a societal problem too I found it more interesting.

When I did Boogie Nights (pictured) and Happiness and Flawless I was dealing with people who have extraordinary problems with intimacy, but not just guys who are having a problem with their girlfriend. Social intimacy problems, people who are literally socially malfunctioning through whatever reason and I found that very interesting. Those parts are extraordinarily different people but they operating pretty much in the same thematic ball park, people struggling with being a misfit socially but in grave need of intimacy. And I just found that very interesting. I think it’s a human dilemma, period, but because those stories deal with a societal problem too I found it more interesting.

Onto another film that was a play: The Ides of March.

That’s true. I think the thing is all scripts have been in a previous life and once the film business comes along it doesn’t really matter. It’s about it’s well written or not and that can come from an article, that can come from a documentary, that can come from someone’s real life, that can come from someone’s imagination which is pretty much informed by their real life, or it can come from a play. Or a book or whatever. So sometimes plays are good that way because it’s already been attacked by a writer so if it’s written well there’s already a lot of real good dialogue and character development there to be mined for the screenplay. But I don’t go looking for it, no. It just happened by chance. But I think where they come from is not what is ultimately important. It’s what the screenwriter ultimately does with it. So long as it’s not the playwright. So long as it’s somebody else.

Did you see the play Farragut North on which The Ides of March is based? (Pictured below, Hoffman with George Clooney and Ryan Gosling)

I didn't. I wish I had. I have a lot of friends who saw the play and were talking about it. I know actors that were in the production.

I didn't. I wish I had. I have a lot of friends who saw the play and were talking about it. I know actors that were in the production.

What lured you in?

You never really know how you do anything in a way because you just end up doing it. It’s based on some many bits of information, you know what I mean, it’s based on so much. I was out of town working somewhere when somebody said, “George called.” Actually George texted me, because I knew George but he is friends with my friend Sam Rockwell. He called Sam and said, “Give me Phil’s number” and Sam just gave him my number because we all knew each other so he just texted about this thing so I called him, we talked about it. It sounded interesting. I had heard of the play so I had a little vibe of what the story was so he sent the screenplay and the screenplay was pretty great. It’s also a really neat part, just because of the nature of the role. I don’t feel I’ve played a role like that before. There’s something about that role that is about being my age and being where I am in my life now. That’s kind of nice, to start approaching roles to do with who I am. It’s not about being young any more, so it’s about something else. It’s about issues to do with your 40s and 50s and stuff which I think is good. And so it was all that information coming in and reading it and talking to George again and scheduling and then eventually I said, "Yeah, I’m going to do it."

Is there any analogy between the dynamic of this film and the entertainment industry in which those actors who force themselves into the belly of mammon perhaps suffer in the same way?

I think there’s a price that’s always paid. I don’t think that’s an analogy that George is consciously making. I don’t think the film is either. But I think the story could exist in many different environments. That’s why I’ve already had mini arguments with people. I don’t see it as a political film. The nature of it really can take place anywhere. Is there a price to pay for succeeding in a way that you desire? Is there a price that’s paid for wining at all costs?

Have you ever attempted to win at all costs?

No I’m not like that. I’ve definitely done that to myself, meaning that I’ve definitely demanded things of myself that were tough to deal with. Just times in my career where I’ve had certain jobs that were very difficult and I knew they would be very difficult and I just wouldn’t settle and kind of what you put yourself through to do as well as you can. Because anything else is unbearable to deal with: that kind of pressure you’re putting on yourself, that kind of ambition to do so well is there. But it doesn’t have to do with someone else. It doesn’t have to do with a competition. I think actors competing is very weird. I’ve never understood that. I can understand having envy or jealousy but usually that just makes you want to be better. The thing is that ultimately actors need each other. We don't want to really get off on the wrong foot because ultimately we’re going to have to work together because actors need each other. So they ultimately get along, they work it, they figure it out. They can’t stay that way too long.

Watch the trailer for The Ides of March

Should actors get involved in politics?

If they want to be politicians. I’m not one of those people that thinks actors shouldn’t be politicians; if ultimately that’s there it leads them and they don’t want to be actors any more and they want to get into politics, then why not? If they care and they want to do it, then they are just as qualified as anyone else to get into politics.

Philip Seymour Hoffman for president?

Never. No, I’ve no desire to be in politics. Not at all.

Are there roles out there you kick yourself you didn't get?

No, not really because again after the fact you’re like, “I didn’t get it so I’m not supposed to play it.” It’s really not something to lose sleep over because once it’s played by somebody else it’s done. It’s of no interest any more.

Does it depress you when films tank?

No. There’s films that you think are great that nobody sees and there’s films where you go, it is what it is, and everybody sees it. For me to spend time worrying about did they like it or not like...If I like it I like it, if I don’t like it I don’t like it. What other people feel is their business. I might not like a film but I’ll have people come up to me, more than with some other films that I like, and they’ll be like, “I’ve seen that film 10 times with my daughter, and it means so much to my daughter and I just want to thank you for your time.” You feel like, what am I sitting here wasting my time worrying about if they like it or not? If somebody likes it they like it. The most important aspect is my work is worthwhile.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Comments

PSH interviews are part of