P E Caquet: The Bell of Treason review - the sacrifice of Czechoslovakia | reviews, news & interviews

P.E.Caquet: The Bell of Treason review - the sacrifice of Czechoslovakia

P.E.Caquet: The Bell of Treason review - the sacrifice of Czechoslovakia

1938 revisited through the eyes of the Munich Agreement's victims

It was 80 years ago next month that Neville Chamberlain returned with the good news of peace in our time. The Munich Agreement was greeted as a triumph for the appeasers. The price Britain had to pay was a minor stain on its conscience: the decimation of Czechoslovakia.

And perhaps that lacuna prevails to this day. Precisely who the Czechs and the Slovaks - plus the Ruthenians and the Sudeten Germans - were, and the ordeal they underwent in 1938, is the subject of The Bell of Treason, in which the historian P.E. Caquet (pictured below) looks at the crisis which culminated in the Munich Agreement through the other end of the telescope. Not long loosed from the Hapsburg yoke, the young country was, he explains, at once a Mittel-European Ruritania and at the same time “one of the most advanced countries in the world”. His opening chapter, a tour of Czech culture and its flourishing but pacific nationalism enshrined in the gymnastic organisation Sokol, persuasively sets the scene.

Then in February 1938 Hitler vowed to protect the 10 million Germans domiciled in neighbouring territories. The Anschluss followed in mid-March. Czechoslovakia, rather than cower, drew comfort from its treaty with France assuring mutual protection, and the considerable strength of its own military defences. France, meanwhile, hoped and assumed that it would find moral and strategic support from a Britain which had no standing army to speak of. The drama played out in a series of plans for the accommodation of Sudeten German needs. Henlein, the Sudetenland’s little Hitler, rattled sabres and screeched demands including a clause which insisted that Sudeten Germans be given the complete freedom to adhere to the “German world outlook”, by which he meant a Nazi Weltanschauung. The Reich’s bellicosity also found a voice in Goebbels, who charmingly referred to exiles fleeing south into Czechoslovakia as “corpses on holiday”.

Then in February 1938 Hitler vowed to protect the 10 million Germans domiciled in neighbouring territories. The Anschluss followed in mid-March. Czechoslovakia, rather than cower, drew comfort from its treaty with France assuring mutual protection, and the considerable strength of its own military defences. France, meanwhile, hoped and assumed that it would find moral and strategic support from a Britain which had no standing army to speak of. The drama played out in a series of plans for the accommodation of Sudeten German needs. Henlein, the Sudetenland’s little Hitler, rattled sabres and screeched demands including a clause which insisted that Sudeten Germans be given the complete freedom to adhere to the “German world outlook”, by which he meant a Nazi Weltanschauung. The Reich’s bellicosity also found a voice in Goebbels, who charmingly referred to exiles fleeing south into Czechoslovakia as “corpses on holiday”.

As Caquet carefully explains, the concept of ethnic and cultural purity among Sudeten Germans was a chimera. The grouping had acquired its name only in the early part of the 20th century. Languages intermingled, and so did their speakers. Uncoupling them, reckoned one politician, “is not for the politician to solve any more, but for the psychiatrist”. But if it came to a fight, Czechoslovakia, with a fired-up army backed by Britain and France, would have been a match for German forces which had yet to reach peak military strength. But the allies didn’t fancy war, and were easily bullied by a ranting Hitler.

The story that unfolds is one of desperate diplomacy, appalling betrayal and quite staggering naivety. The British were especially eager to pull the wool over their own eyes. "He is, I am sure, an absolutely honest fellow," mused the British diplomat Frank Ashton-Gwatkin of Henlein. Chamberlain was similarly doveish about Hitler: “Here was a man who could be relied upon when he had given his word,” he concluded on visiting Germany. And after he went back: “Hitler had certain standards… he would not deliberately deceive a man whom he respected.” One Czech diplomat called Chamberlain “the errand boy of gangsters”.

Munich, at least to the Czechoslovaks, was not an inevitable outcome. Hope sprang eternal: the night before the conference the newspapers confidently assumed that Britain and France would not forsake them. In fact only two envoys were allowed to travel to Munich, and then only to be confined to their hotel room and told the bad news.

Munich, at least to the Czechoslovaks, was not an inevitable outcome. Hope sprang eternal: the night before the conference the newspapers confidently assumed that Britain and France would not forsake them. In fact only two envoys were allowed to travel to Munich, and then only to be confined to their hotel room and told the bad news.

This section of the story was imaginatively told in Robert Harris’s most recent thriller Munich, but even he found little room to accommodate the Czechs in his pages. Caquet reports the chilling words of Ashton-Gwatkin to the envoy Hubert Masaryk: “if you do not accept, you will find yourselves facing Germany alone. The French may sugar this with fine phrases but, believe me, they are of the same view and have lost interest in your fate.” Masaryk coolly observed Chamberlain’s intoxication with “the idea for having prevented war” as the French premier Daladier blushed and sweated in silent shame at his country’s failure to honour its treaty with Czechoslovakia. The other enjoy, Mastny, burst into tears. So did all Prague the following day. (There is a lot of public weeping in this story)

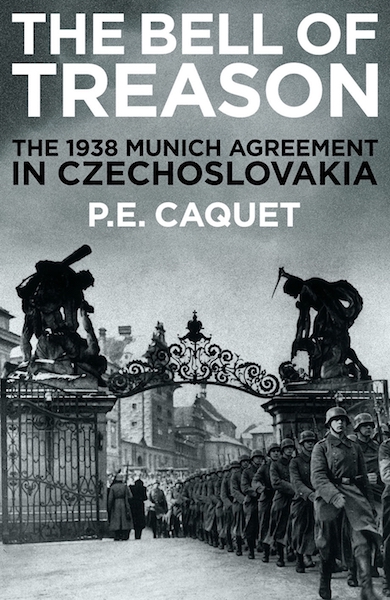

In the summer of 1938, when it saw the way the wind was blowing, the newspaper Přítomnost predicted that “future historians … will be tempted to rate the policy of these big democracies as dreadful”. Caquet, the latest of those future historians, describes the sacrifice of Czechoslovakia with proper attention to every minute twist and turn, without ever taking his eye off the human story. There could be more on the subplot of Jewish anxiety. A more outright absence is cartographical: no history of a territorial dispute could have a greater need of maps, but there are none. And alas the only illustration is the jacket image (pictured) which shows the Wehrmacht marching through the gates of Prague castle, the outcome of everything this gripping history leads up to.

Let us leave the last prophetic words to a chorus of writers issued to newspapers across the world. “We invite you to explain to the publics of your countries that if a small and peaceful nation such as ours… is forced to fight, we will fight not just for ourselves, but for you and for the common moral and spiritual property of the free and peace-loving peoples of the world.” One of the signatories was Karel Čapek, the great Czech novelist and playwright who, aged 48, had perhaps the good fortune to die on Christmas Day 1938, three months before the German invasion against which Czechoslovakia was denied the chance to defend herself.

- The Bell of Treason: The 1938 Munich Agreement in Czechoslovakia by P.E. Caquet (Profile Books, £20)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Comments

'decimation'? Surely this is