Robert Harris: Munich review - reselling Hitler | reviews, news & interviews

Robert Harris: Munich review - reselling Hitler

Robert Harris: Munich review - reselling Hitler

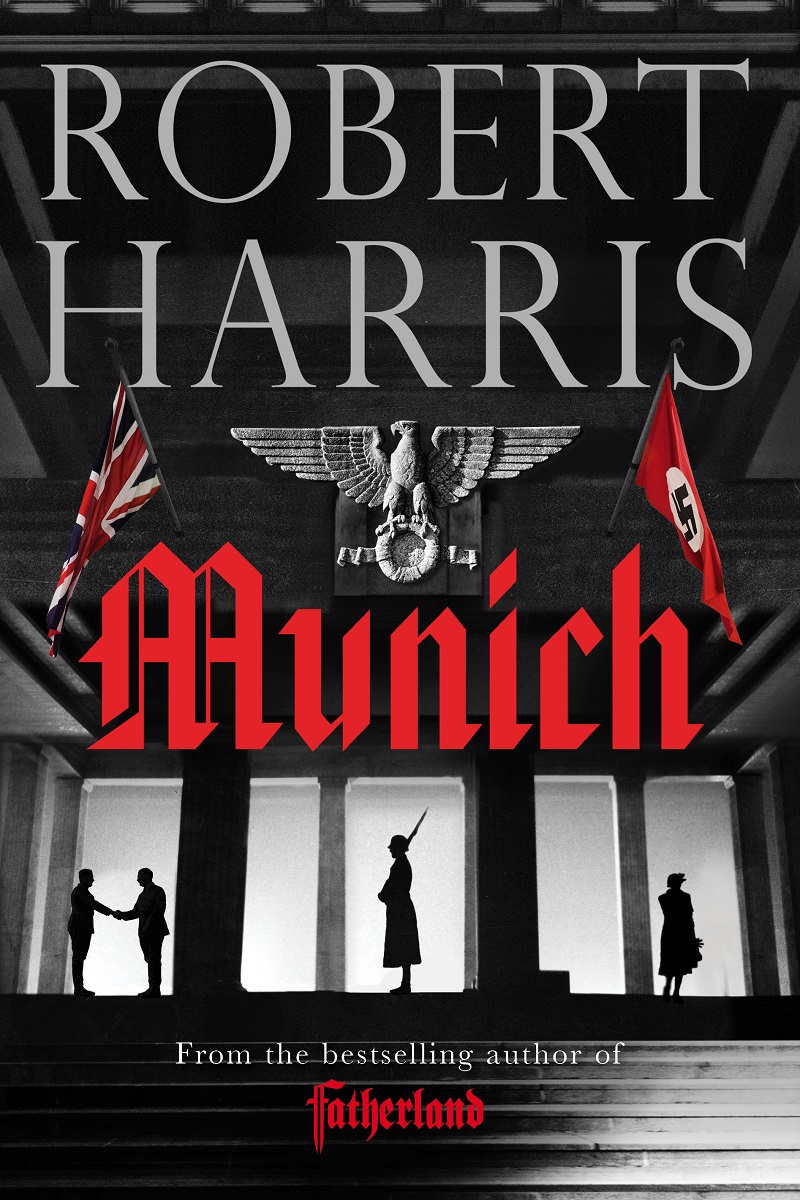

The author of Fatherland revisits the Reich to tell the story of peace in our time

Robert Harris’s first book about Hitler told the story of the hoax diaries which seduced Rupert Murdoch and Hugh Trevor-Roper. After Selling Hitler (1986) came Fatherland (1992), another fake story about the Führer. In that alternative history the Third Reich had stuck to a non-aggression pact with Britain and expanded unopposed into the lebensraum of the Soviet Union.

That infamous piece of paper has lured Harris back to Nazi Germany after 25 years. This time he remains committed to documented reality. On the first page we know where we will be by the last, and what will come after. Can it, like The Day of the Jackal, be thrilling anyway?

Into the story of the top brass who converged on Munich – Hitler’s gang of polished turds, Neville Chamberlain’s coterie of post-Victorian nabobs – Harris has insinuated two witnesses in their twenties. Hugh Legat is an underling at Number 10 on secondment from the Foreign Office, a stiff young fogey whose superiors are jealous of his swift advancement. He is our guide round central London where, in anticipation of war, barrage balloons float aloft and trenches are being dug into Green Park. Paul von Hartmann, debonair and high-born, is of a similar rank at the Foreign Ministry in swastika-festooned Berlin, and one of several conspirators plotting to do away with the little corporal. What links them is a friendship formed as students at Balliol, and their fluency in each other’s language. They haven’t communicated since the Nazis’ electoral putsch, but Munich beckons and various shady players contrive to get them both listed on the passenger manifest to open up a back-door communication.

The first half involves much procedural throat-clearing as the two parties navigate a diplomatic path towards the summit at which the Sudetenland of Czechoslovakia will be handed back to Germany. As ever Harris has done lashings of research so that for anyone wanting to know how the Munich Agreement came about, this is a fun way to find out. One or two of the scenes in Number 10 have the stodginess of setpiece melodrama, but Harris has an eye for colour amid the grey moustaches and yards of pinstripe. Duff Cooper, loitering in corners, exudes “a vague late-night whiff of whisky and cigars and the perfume of other men’s wives”. Meanwhile in Germany Harris homes in on the squalor beneath the pageantry, most overtly in the latrine on the Fuhrer’s train where Swastikas are even embossed on the taps.

Harris is alive to the symbiotic consonance linking London and Berlin. On one side are men called Gort and Syers, on the other Kordt and Sauer, the last an unsavoury SS Rottweiler with the scent of treachery in his nostrils. But what most fascinates Harris are the two main players. The statesman who waved that piece of paper is a dogged negotiator, a complex mixture of shy and vain, improbably greeted as a heroic saviour in Munich. Half stuffed shirt, half wise old bird, he is variously described as "corvine", with a "hawk-beak" profile, likened to a "blackbird".

Harris is alive to the symbiotic consonance linking London and Berlin. On one side are men called Gort and Syers, on the other Kordt and Sauer, the last an unsavoury SS Rottweiler with the scent of treachery in his nostrils. But what most fascinates Harris are the two main players. The statesman who waved that piece of paper is a dogged negotiator, a complex mixture of shy and vain, improbably greeted as a heroic saviour in Munich. Half stuffed shirt, half wise old bird, he is variously described as "corvine", with a "hawk-beak" profile, likened to a "blackbird".

Hindsight has turned appeasement into a dirty word; this portrait wipes away much of the mud which clings to Chamberlain. The shaggy-dog plot turns on Hartmann’s quest to present Chamberlain with evidence of Hitler's long-term plan for military aggression, to which the Prime Minister has no choice but to respond with proper pragmatism. Harris doesn't entirely let him off. At the climactic moment, when Chamberlain holds the piece of page at arm’s length so as not to use his glasses, to Legat he looks “like a man who had thrown himself on to an electrified fence”. It doesn’t look quite that drastic in the archive footage on YouTube.

There’s much less scope to say anything fresh about Hitler’s dismal lack of presence. Harris is surprised by the softness of the Führer’s non-oratorical voice (of which Bruno Ganz, when researching for Downfall, could find only one recorded example) and reports that he reeked of body odour. He has Hartmann sneak into the bedroom of Hitler’s late niece Geli Raubal and draw his own conclusions about the nature of their relationship. But perhaps there’s another dimension to this portrait. Harris has admitted to using the machinations of ancient Rome as a means of writing about imperial America at one remove. In the person of a disdainful, lying demagogue who hoodwinked an electorate into putting him in office, a ticking bomb who is grouchy whenever crossed or denied the limelight, he may well be doing that again. As someone says of this Hitler, “No one really knows what’s in his mind.”

Harris peppers the canvas with incidental detail. The Czechoslovak delegation, who are about to be checkmated by the four foreign powers, play chess in their hotel room. A band strikes up "Doing the Lambeth Walk" to make the British feel at home. Harris has fun working up cartoonish pen portraits of "Musso" and his foreign minister/son-in-law Ciano (Jared Kushner, anyone?). There's much thrillerish toing and froing to bring Legat and Hartmann together. Less effort is expended on their back story. An idyllic holiday in Munich in the summer of 1932, involving a romantic menage à trois, is sketched in a little perfunctorily. So is Legat’s forlorn marriage to a woman who views the binding nature of her altar vow rather as Hitler treats non-aggression pacts.

While Harris briefly offers a glimpse of forthcoming brutalities, you sense that he’s already rolled that rock up the hill in Fatherland. What he’s nerdily interested in – as in Conclave, his masterly snoop inside the Vatican's citadel – is getting his characters through closed doors to eavesdrop on what happens there. For all its energetic traipsing up and down the corridors of power, the facts won't quite allow Munich to be a high-octane page-turner. But as a considered warning from history, it exerts a powerful grip.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Add comment