The Noughts were a bonanza time for builders, scientists and bureaucrats in the dance arena, throwing up numerous fine dance venues and bases, collaborating intellectually with modern choreographers, or targeting social minorities, but the blazing new trend that captured public imagination dodged all of those - it came up from the street. As if to show that dance doesn’t need all these people to organise it into existence, hip hop was the powerful new physical force in the land, providing all the things that the contemporary dance movement of the Nineties seemed increasingly to ignore. The public, after a generation of cool abstract dance, was gagging for drama, anger, individuality and physical brilliance on stage - and they began to get it.

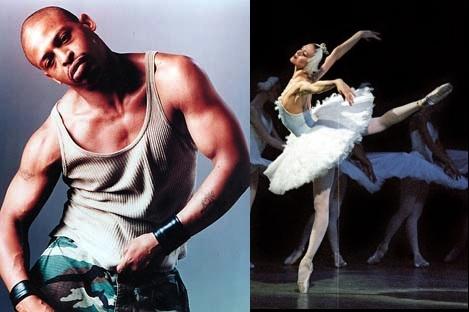

Long claimed the province of violent US rappers with undesirable lives, hip hop was translated with genius to theatres by Rennie Harris from Philadelphia. His Rome and Jewels, a blisteringly dramatic and imaginative hip hop version of Romeo and Juliet shown in London (October 2001, starring Rodney Mason, main picture), was a watershed for British audiences; Londoner Jonzi D energetically collaborated with Sadler's Wells in 2004 to start up a tentative hip hop spring festival. Now the two big Christmas dance shows at the Barbican and South Bank Centre are hip hop productions, both generated in London. Britain is chock-full of kids, black and white, learning locking, popping and krumping. Youtube has almost half a million videos of streetdance, categorised carefully into their component techniques, mostly filmed by mobiles in the streets, all showing the urgent passion of its practitioners to compete in thrills but also in proudly expressive finesse. These videos were key in the arrival on mainstream TV, via Britain’s Got Talent, of a self-taught young white Warrington boy, George Sampson, and then two exceptional London crews, Diversity and Flawless. Mainstream Britain has now seriously “got” hip hop.

Meanwhile, builders never had it so good. Thanks to dance-interested arts ministers such as Tessa Blackstone and Estelle Morris, diggers spread across Britain erecting dance buildings. Following the landmark redevelopments of the Royal Opera House and Sadler’s Wells at the end of the Nineties, Birmingham Royal Ballet got a remodelled base at the Hippodrome (2001) with world-class new therapy facilities, the Royal Ballet School (2003) and the Laban Centre (2003) en route to new HQs, in Leeds Northern Ballet Theatre and Phoenix Dance will move into a grand new space next year (pictured recently, right), and, long overdue, Siobhan Davies won a beautiful London studio base (2006, pictured below left) for contemporary choreographers.

Meanwhile, builders never had it so good. Thanks to dance-interested arts ministers such as Tessa Blackstone and Estelle Morris, diggers spread across Britain erecting dance buildings. Following the landmark redevelopments of the Royal Opera House and Sadler’s Wells at the end of the Nineties, Birmingham Royal Ballet got a remodelled base at the Hippodrome (2001) with world-class new therapy facilities, the Royal Ballet School (2003) and the Laban Centre (2003) en route to new HQs, in Leeds Northern Ballet Theatre and Phoenix Dance will move into a grand new space next year (pictured recently, right), and, long overdue, Siobhan Davies won a beautiful London studio base (2006, pictured below left) for contemporary choreographers.

All fine and dandy for buildings then, but they needed to be paid for by good box-office, so more conservative taste ruled everywhere. Noughty taste flattened, broadened and dulled. Younger critics and administrators were now growing up without experience of the individualistic risks and thrills of innovative eras of the past, and nowhere more so than in ballet. To me this was a decade when ballet lost its mojo.

All fine and dandy for buildings then, but they needed to be paid for by good box-office, so more conservative taste ruled everywhere. Noughty taste flattened, broadened and dulled. Younger critics and administrators were now growing up without experience of the individualistic risks and thrills of innovative eras of the past, and nowhere more so than in ballet. To me this was a decade when ballet lost its mojo.

Today’s arts scene is much more socially engineered than before, controlled and regimented by focus group, where audiences are divided up and targeted by colour, culture and age. In this bureaucratic factory of aspirations, the talents who flourished were those who possessed alongside choreographic energy an equally valuable social savvy: Akram Khan, Wayne McGregor, Russell Maliphant, Richard Alston.

Some inspiring loners gradually got squeezed out of view: Jonathan Burrows and Henri Oguike are the ones whose absence from regular stage performance is most painful, because their concerns are firmly about sharpening their art, rather than doing good. Burrows’ hilarious, stimulating trilogy of duets with composer Matteo Fargion (The Place, 2003-5) and Oguike’s blistering Front Line (touring the UK from 2000, picture below by Chris Nash for HODC) were landmarks in my memory, and both men kept rising in inspiration through the decade, while others trod water or fell.

Ballet is where I felt most unease. The coming and going of directors at the Royal Ballet and English National Ballet betokened an increasing mismatch of aspirations between candidate and boss expectations. Ross Stretton and Matz Skoog were in a broad sense two representatives of change brought in, then turbulently replaced by representatives of stasis, Monica Mason and Wayne Eagling - and can anyone honestly say that the Royal Ballet and ENB today are forward-looking? To my mind the grip of finance directors and box offices over companies which should be determinedly spending taxpayers’ money on moving art ahead is happening, in part, because ballet refuses so far to take an intellectual grip of its tradition. Thus it falls readily to the mass forces of twee (see dispiriting recent redesigns at Monica Mason's Royal Ballet).

The most important intellectual thing that has happened to ballet in decades - which is the Russians’ engagement with the original 19th-century texts of classical ballets 10 years ago - seems temporarily stalled. In St Petersburg and Moscow, the overwhelming enthusiasm of British and American audiences for the Mariinsky’s fascinating time-warp "original versions" of The Sleeping Beauty (Covent Garden, August 2000) and La Bayadère (Covent Garden, August 2003) counted for less than the stolid resistance of xenophobic Soviet-raised ballet coaches to change. Now the reconstruction movement fiddles academically at the edges of minor works, rather than tackling the great theatre challenges of researching and defining the rules about what is and what is not Swan Lake or Giselle, and then protecting these from pollution. If those old works and period styles could be properly defined, it would free generations of ballet directors to create new stories, and give the public something different to experience. As William Forsythe told me in an interview, if Giselle was banned, new generations would have to make their own.

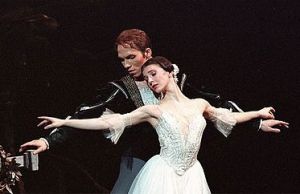

Still, that stultification in repertoire did not stop the Royal Ballet having a glittering decade as far as star performers were concerned. Although ENB has been blessed by the Thomas Edur/Agnes Oaks partnership, it’s the Royal’s sublime foursome who will stand out for this period: Alina Cojocaru, Johan Kobborg, Tamara Rojo and Carlos Acosta. Acosta ends the decade as probably the most popular ballet dancer in UK history since Nureyev, crowning his fabulous career with an iconic Spartacus with the Bolshoi; the Cojocaru/Kobborg partnership started in 2001 and rapidly became the ballet world’s most sought-after guest act (pictured left in Giselle by Tristram Kenton), her glowing delicacy offset by his magnetic dramatic immediacy; meanwhile Rojo was transcendent, evolving herself as an Odette/Odile for the ages as well as stunning spectators with her unmatched theatrical force in MacMillan roles. The fact that all four are non-British speaks volumes for the importance to the world of the Royal Ballet’s core choreographic treasures, the oeuvre in particular of MacMillan, who 17 years after his death is the choreographer most likely to win international permanence in decades to come.

Still, that stultification in repertoire did not stop the Royal Ballet having a glittering decade as far as star performers were concerned. Although ENB has been blessed by the Thomas Edur/Agnes Oaks partnership, it’s the Royal’s sublime foursome who will stand out for this period: Alina Cojocaru, Johan Kobborg, Tamara Rojo and Carlos Acosta. Acosta ends the decade as probably the most popular ballet dancer in UK history since Nureyev, crowning his fabulous career with an iconic Spartacus with the Bolshoi; the Cojocaru/Kobborg partnership started in 2001 and rapidly became the ballet world’s most sought-after guest act (pictured left in Giselle by Tristram Kenton), her glowing delicacy offset by his magnetic dramatic immediacy; meanwhile Rojo was transcendent, evolving herself as an Odette/Odile for the ages as well as stunning spectators with her unmatched theatrical force in MacMillan roles. The fact that all four are non-British speaks volumes for the importance to the world of the Royal Ballet’s core choreographic treasures, the oeuvre in particular of MacMillan, who 17 years after his death is the choreographer most likely to win international permanence in decades to come.

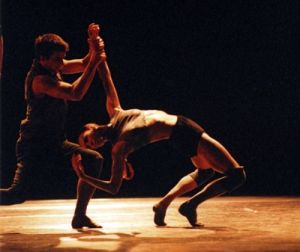

Irek Mukhamedov and Darcey Bussell retired in memorable performances of Mayerling and Song of the Earth respectively, but Sylvie Guillem took a glorious new second wind for her phenomenal career by moving with the Ballet Boyz (two other Royal Ballet émigré mavericks) into contemporary ballet. In 2003 they took the initiative to press the stagnant Royal Ballet to stage a neck-prickling trio by Russell Maliphant, Broken Fall (pictured right, Guillem and William Trevitt, photo by John Ross) at the Royal Opera House - since then Guillem and the Ballet Boyz have become a new axis for innovative thinking in ballet, the shot in the arm that the arts media, among other people, was longing for.

Irek Mukhamedov and Darcey Bussell retired in memorable performances of Mayerling and Song of the Earth respectively, but Sylvie Guillem took a glorious new second wind for her phenomenal career by moving with the Ballet Boyz (two other Royal Ballet émigré mavericks) into contemporary ballet. In 2003 they took the initiative to press the stagnant Royal Ballet to stage a neck-prickling trio by Russell Maliphant, Broken Fall (pictured right, Guillem and William Trevitt, photo by John Ross) at the Royal Opera House - since then Guillem and the Ballet Boyz have become a new axis for innovative thinking in ballet, the shot in the arm that the arts media, among other people, was longing for.

Scottish Ballet and Birmingham Royal Ballet fought against much less generous central grant than Covent Garden enjoys, but both flourished with hearty support from their cities, Scottish as a new international modern ballet company under Ashley Page, BRB being both reassuringly English and yet creative under David Bintley. Bintley remains the most ambitious dance-maker at the helm of almost any ballet company worldwide, forging, if with variable success, several full-length works with big music commissions notably from the fine John McCabe. Around the major world companies only Alexei Ratmansky’s tenure at the Bolshoi Ballet looked as confidently aimed towards creativity, but the politics and financial mire of that labyrinthine theatre prematurely drove Ratmansky off to a less stressed life in New York.

Ballet history passed with the deaths at immense age of four giants: Dame Ninette de Valois (2001) and Dame Alicia Markova (2004), the two miracle-workers of British ballet’s birth, visionary and ballerina, united in their youth with Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, whose centenary this year was marked decently by ENB and Rambert, cursorily by the Royal Ballet, and, in 2009, Merce Cunningham, still wintergreen and creative at 90, and dance-theatre's queen, Pina Bausch (all pictured above).

Other trends: the outdoor or cinematic transmission of ballet from Covent Garden and a long overdue ballet recording campaign, but the shrinkage of arts stories on TV except where heartwarming Billy Elliott rags-to-riches family interest could be found. The rise of important projects to develop future directors, such as the Clore Leadership Programme and Dance East’s Directors Retreat. The verbose PR wind behind science as dance’s fashionable friend, rather than art. The writing of important biographies of Margot Fonteyn (by Meredith Daneman, 2004) and Kenneth MacMillan (by Jann Parry, 2009).

Memorable nights of the Noughties

Merce Cunningham’s Biped (Merce Cunningham Dance Company, Barbican, October 2001), still the most poetic imagining yet of dance in the computer age, a dialogue between the soul and the brain (pictured left)

Merce Cunningham’s Biped (Merce Cunningham Dance Company, Barbican, October 2001), still the most poetic imagining yet of dance in the computer age, a dialogue between the soul and the brain (pictured left)

William Forsythe’s Eidos: Telos (Ballett Frankfurt, Sadler's Wells, November 2001), a wholly extraordinary speech-and-dance three-acter inspired by the Greek death myths of Eurydice, Arachnis and Persephone (Dana Caspersen the magnetic central performer)

Christopher Wheeldon’s Polyphonia (New York City Ballet, Edinburgh Festival 2001 and Royal Ballet, 2006) and Continuum (San Francisco Ballet, Edinburgh Festival 2003 & Morphoses, Sadler's Wells, October 2009), a pair of Ligeti ballets that show genius (Wendy Whelan his outstanding interpreter)

Alexei Ratmansky’s The Bright Stream (Bolshoi Ballet, Covent Garden, August 2006), brilliant entertainment set on a Soviet collective farm, imagine. Cherishable corn (Maria Alexandrova pictured right).

Alexei Ratmansky’s The Bright Stream (Bolshoi Ballet, Covent Garden, August 2006), brilliant entertainment set on a Soviet collective farm, imagine. Cherishable corn (Maria Alexandrova pictured right).

Mark Morris’s V (Mark Morris Dance Group, Sadler’s Wells, October 2001), a Schumann dance that crystallises the darkest and the blithest of this witty, humane choreographer.

Matthew Bourne’s Play Without Words (National Theatre, London, August 2002), Sixties Chelsea in triplicate, Bourne’s most stimulating and sophisticated creation yet, made thanks to Nick Hytner's encouraging NT regime (pictured left).

Matthew Bourne’s Play Without Words (National Theatre, London, August 2002), Sixties Chelsea in triplicate, Bourne’s most stimulating and sophisticated creation yet, made thanks to Nick Hytner's encouraging NT regime (pictured left).

Petipa/Ivanov's Swan Lake, interpretations of Odette/Odile by Uliyana Lopatkina (Mariinsky, Covent Garden, July 2001 and August 2009) and Tamara Rojo (Royal Ballet, Covent Garden, December 2004), for me the two most illuminating lights who shine today upon this eternally mysterious work of art.

Highlights ahead in 2010

Mark Morris Dance Group, unmissable chance to see the American's Handel masterpiece L'Allegro, il Penseroso ed Il Moderato, London Coliseum, 14-17 April.

Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch, posthumous visit for this iconic company, now directed by two of her veteran dancers, performing her amusing, scabrous Kontakthof in two versions, for over-65s and teenagers, Barbican Theatre, London, 1-4 April 2010.

Royal Ballet premieres ballets by two youngsters, Jonathan Watkins, 19 February-4 March, and Liam Scarlett, 5-15 May, Royal Opera House, London.

Birmingham Royal Ballet 20 Years in Birmingham Celebration, 9 & 10 March, Birmingham Hippodrome.

Akram Khan premieres Gnosis, Sadler's Wells Theatre, London, 26-27 April.

Royal Ballet MacMillan’s excoriating last masterwork The Judas Tree (pictured right) revived in 80th anniversary triple bill of his work, 23 March-15 April., Royal Opera House, London.

Royal Ballet MacMillan’s excoriating last masterwork The Judas Tree (pictured right) revived in 80th anniversary triple bill of his work, 23 March-15 April., Royal Opera House, London.

Bolshoi Ballet, Royal Opera House, 19 July-8 August, repertoire includes Spartacus, Ratmansky’s Russian Seasons, Le Corsaire and Don Quixote.

Merce Cunningham Dance Company, another posthumous visit for a giant, with a UK premiere of his final work, Nearly Ninety, with music by Sonic Youth. Barbican Theatre, London, 26-30 October.

Birmingham Royal Ballet, a new Cinderella by David Bintley, designed by John D Macfarlane, December, Birmingham Hippodrome.

Add comment