The term most often used about Berlin director Angela Schanelec’s filmmaking seems to be “elliptical”, and her latest film, I Was at Home, But..., which won the Best Director award at Berlinale 2019, is no exception. Approaching it is like an associative process – you absorb elusive hints, as much from visual elements as from any suggestion of story, trying to gradually assemble something, almost like creating a mosaic. Except that Schanelec determinedly avoids endorsing any final picture: links are left open, and narrative, such as it is, is very much secondary to mood.

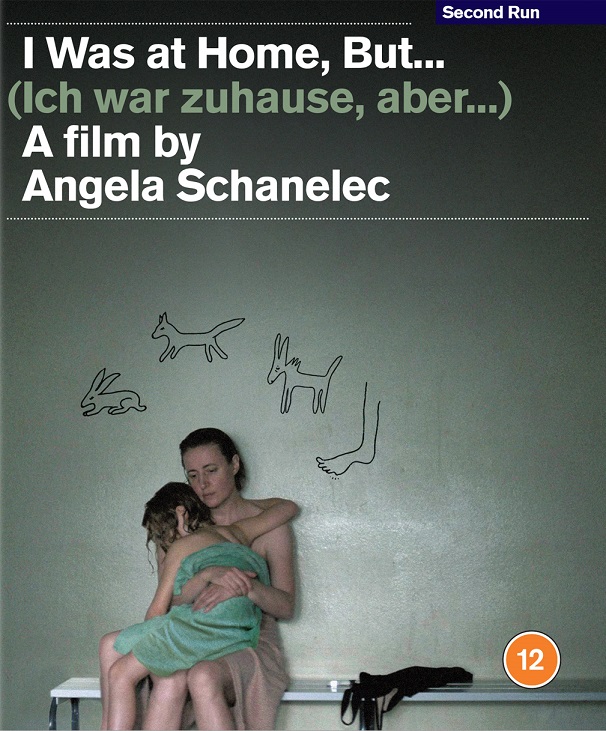

And the mood of I Was at Home, But... is bleak. There’s a fine half-hour interview with the director as one of the extras on this Second Run release, in which Schanelec talks of the theme of motherhood in the film, but it’s tempered by such a profound sense of grief and loss as to test that family bond to the extreme. The central role of Astrid, a woman rather more than on the verge of a nervous breakdown, is played by Schanelec regular Maren Eggert, though Eggert seems to live the role far more than she “plays” it: it’s a dualism that reflects more abstract themes – of “being” and “becoming”, and the contrast of actorly representation and real life – that are brought up here in more consciously conceptual contexts. Eggert achieves absolute naturalism of performance in a film that is itself fragmentedly non-naturalistic.

There are rare scenes that communicate emotion with piercing intensity. In one, we watch Astrid in her enduring pain reject the elemental consolation of closeness that her two young children instinctively offer, and come back to offer repeatedly despite her angry rejection; in another, the source of that original pain is suggested in a graveyard scene that segues into a family memory, a moment of subjective explication that is all the more powerful for being set to the film’s only non-diegetic music, a blues cover version of Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” by M Ward that fits exquisitely here.

There are rare scenes that communicate emotion with piercing intensity. In one, we watch Astrid in her enduring pain reject the elemental consolation of closeness that her two young children instinctively offer, and come back to offer repeatedly despite her angry rejection; in another, the source of that original pain is suggested in a graveyard scene that segues into a family memory, a moment of subjective explication that is all the more powerful for being set to the film’s only non-diegetic music, a blues cover version of Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” by M Ward that fits exquisitely here.

But such moments are the exceptions in a film that strikes more for its emotional coldness, its sense of individual and social alienation that’s matched by a climate that moves from the relative visual plenty of autumn into “grey Berlin winter”, as it’s referenced here (though nothing specifically suggests Berlin in the film, which has, if anything, a small-town feel). Such determinedly everyday settings allow Schanelec and especially her collaborators, cinematographer Ivan Markovic and production designer Reinhild Blaschke, to create what one critic has termed “affective images”, particularly exterior scenes that capture the chilly beauty of greys or associated darker colours that are spotted with enormous care and precision by the barest suggestion of something brighter, a single dab of mustard or red. The accomplishment of such mood-painting only goes a certain way, however; the poise itself can become oppressive.

For the defining register of I Was at Home, But... is one of silence, that absence that is suggested by the second part of Schanelec’s open-ended (but ultimately reductive) title. If at times silence can be eloquent, at other rare moments when words do come, in almost artificial profusion, their effect is empty (like “talking to a radiator”, as one of Astrid’s set pieces has it). One supporting story strand in the film – it can hardly be called a “sub-plot”, given the absence of plot per se – involves Astrid buying a second-hand bicycle from a man who communicates through an electrolarynx, then returning to dispute her purchase. There’s a profound absurdity to this scene of consciously artificial communication over a matter of such non-empathetic banality that is worthy of the late, great Ukrainian director Kira Muratova – though where Muratova finally relished the absurd, elevating it to a defining principle, for Schanelec it remains a matter of cold-climate pessimism. Another secondary strand, a pronouncedly bare associated story element chiefly notable for the involvement of actor Franz Rogowski, more than endorses such a conclusion.

There’s a particular problem in elucidating a film such as I Was at Home, But..., one that relies for the cumulative power that it may achieve, a sense of accretion of awareness, on the viewer approaching it without foreknowledge; to the extent that Schanelec, an oblique storyteller if ever there was, deals in mystery, each new layer of suggestion needs to be perceived afresh, and not with a critic’s forewarning that such-and-such is happening. It’s far more than a matter of plot spoilers, involving instead the removal of the very basic tenet on which such a cinematic style is built.

Nevertheless, there are elements here that are sufficiently “extraneous” to allow comment. Schanelec frames her film with scenes of animal life from the wild that suggests – at the risk of crude interpolation – the co-existence of cruelty and gentleness. Then there’s a protracted scene at around the half-way mark of the film’s 105-minite run that stands out from the rest for the way it predicates speech, as Astrid berates an acquaintance (played by real-life Berlin filmmaker Dane Komljen) for the artificiality of his artistic approach, prompting, at the very least, consideration of how she might rate the film in which she appears herself.

Finally, and predominantly – at least for the quantity of screen time that it occupies – is the inclusion of elements of a school play production of Hamlet, with scenes of stylised, deadpan rehearsal scattered through the film. We can track down some small degree of association (a dead father usurped, perhaps), and the recital of its text is striking enough in itself – rote text always a substitute for real communication – but what greater degree of equivalence is Schanelec hinting at? Or, given that the play elements somehow intrude into the main material of the film in a way that remains mystifying even after repeated viewings, is she bringing home exactly the non-correlation inherent in her worldview?

What strikes one viewer as poetic ellipsis will be wilful solipsism to another. Cinematic cross-referencing – to Bresson particularly – may provide some respite, but for viewers who undertake this Winterreise, the consolations are chiefly aesthetic. The supporting material on this disc includes three of Schanelec’s short films from the early 1990s from her Berlin Film and Television Academy days, and a new booklet essay by critic Carmen Gray. There’s a sympathetic filmed interview with Schanelec, conducted by Second Run founder Mehelli Modi, which is revealing about how the director “builds” her films “step by step”. Her directorial style is indeed defined by the manner of that construction.

Watch the trailer for I Was at Home, But...

Add comment