There’s no shortage of documentaries about movie stars, film directors and production studios in their heydays, but very little attention has been paid to the cinemas that showed the movies they made or the diverse audiences they attracted.

Opening in the UK after a very successful lap around the world’s film festivals, is Scala!!!! Or, the Incredibly Strange Rise and Fall of the World’s Wildest Cinema and How It Influenced a Mixed-up Generation of Weirdos and Misfits. That breathless title itself hints at the unknown pleasures (and breakneck nostalgia) to come from co-directors Jane Giles and Ali Catterall’s film, a labour of love, five years in the making.

The documentary tells the story of the Scala, an eclectic repertory cinema famous not only for showing European art house and classic Hollywood but, through its status as a members club, screening uncertified lesbian and gay films and horror all-nighters, as well as live gigs and fund-raisers for left-leaning causes from 1978 to 1993. I’m not a particularly impartial journalist on this occasion: the Scala, in its original Fitzrovia incarnation, was the cinema that introduced me as a teenager to the films of Wim Wenders, David Lynch and Billy Wilder.

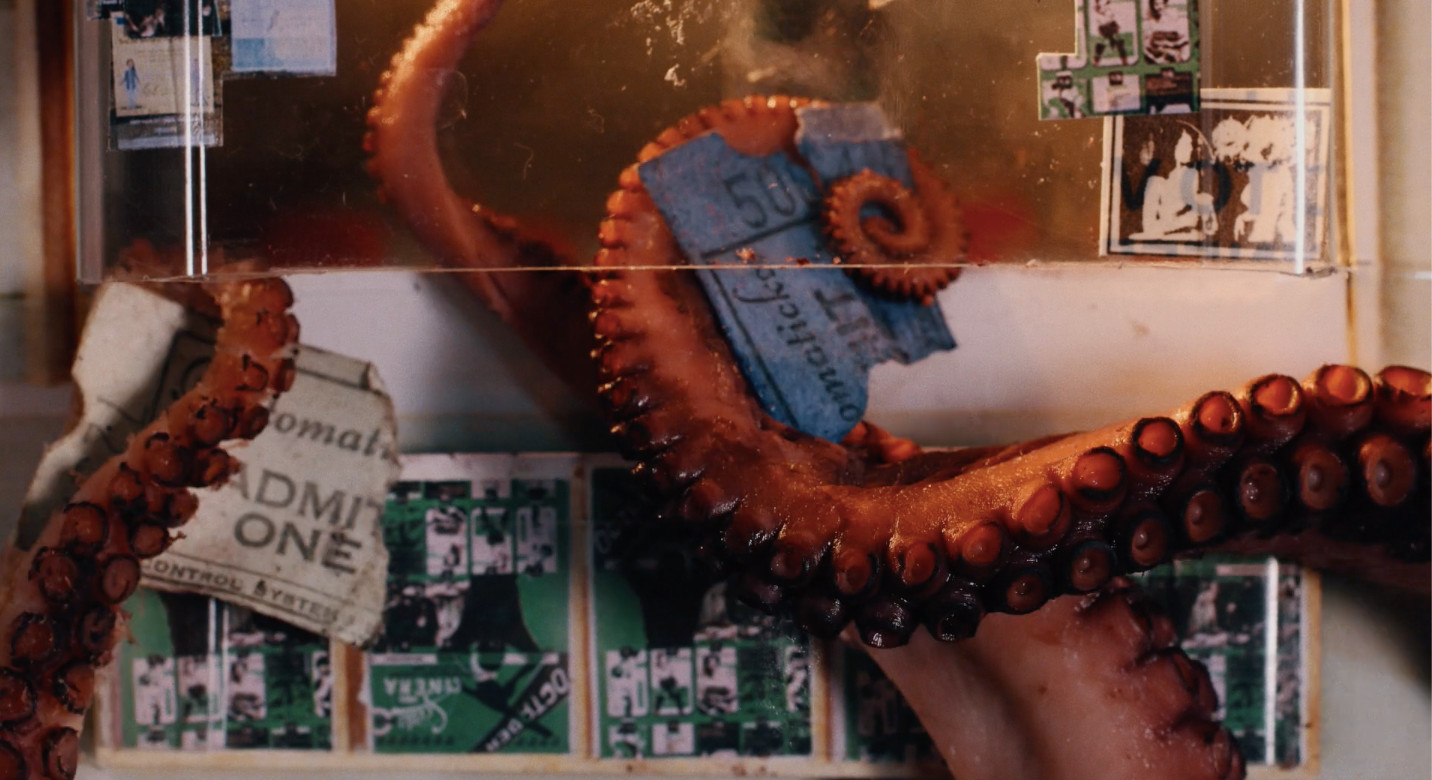

Later when the Scala moved to King’s Cross (pictured above) and I got my first job as a film journalist on the London listings magazine, City Limits, it became a regular haunt. In 1993 I directed interviews in an empty Scala with its founders, the film producers Steve Woolley and Nik Powell. It was for a documentary I made in 1993 for the BBC about their production company, Who’s Crying Now? The Rise and Fall of Palace Pictures. That year the cinema was faced with a perfect storm of rising rent, the deep financial troubles of its founders and a court case involving an unlicensed showing of the then-withheld A Clockwork Orange. Despite a campaign to "Save Our Scala", London lost one of its great movie venues. The cinema has never quite been replaced, although the Garden Cinema and the Prince Charles do their best and the BFI is running a season of Scala favourites on the South Bank and on tour this month.

Later when the Scala moved to King’s Cross (pictured above) and I got my first job as a film journalist on the London listings magazine, City Limits, it became a regular haunt. In 1993 I directed interviews in an empty Scala with its founders, the film producers Steve Woolley and Nik Powell. It was for a documentary I made in 1993 for the BBC about their production company, Who’s Crying Now? The Rise and Fall of Palace Pictures. That year the cinema was faced with a perfect storm of rising rent, the deep financial troubles of its founders and a court case involving an unlicensed showing of the then-withheld A Clockwork Orange. Despite a campaign to "Save Our Scala", London lost one of its great movie venues. The cinema has never quite been replaced, although the Garden Cinema and the Prince Charles do their best and the BFI is running a season of Scala favourites on the South Bank and on tour this month.

The cinema was saved from the encroaching development of Kings Cross and became a music venue with the same name. Jane Giles' history of the Scala became a beautifully produced book (a hefty volume illustrated with reproductions of the extraordinary poster-sized programmes) which led to a documentary. What follows is an edited Q&A with co-directors Ali Catterall and Jane Giles:

What’s your first memory of going to the Scala?

What’s your first memory of going to the Scala?

Jane Giles: In August 1981 I was just 17 and went with a bunch of school friends up from my hometown in Crawley to a horror All-Nighter at the Scala, which had just moved from Fitzrovia. I’d never been to the "old" Scala which my friends said was better, but fell in love at first sight with the Kings Cross building which looked to me like Disney’s magic castle.

Ali Catterall: For me, it was half past four on a Wednesday afternoon in October 1986, I was a student at Kingsway Princeton [a local further education college]. Alan Parker’s Birdy, the thing I’d come to see, was totally up my street, being a dark but oddly uplifting little number about obsession and mental illness. I’d missed it the year before when it had more or less plummeted out of the multiplexes like a dead pigeon. So the Scala, then, was clearly some kind of repository for the weird, the unloved, and passed-over. When the lights barely flickered on, they revealed a gigantic, cavernous fleapit that might as well have been hanging with stalactites; a vast, tattered, beer-stained screen; and cinema seats that looked as if they’d been dragged from a flooded cellar and dried out in a skip.

How was the Scala different from other repertory cinemas?

Jane Giles: There were several rep cinemas in London at the time, but the Scala was the only one which consistently showed Saturday All-Nighters in addition to its daily-changing programme of double or triple bills, plus live gigs and night clubs. And its programme range was wider and more eclectic than other cinemas, bringing experimental film and shorts into the mix with arthouse, classics and cult movies. The Scala was a membership cinema, and the content of its ‘greatest hits’ tended to be more extreme than that of films shown at other cinemas.

When you first pitched the idea of making a documentary about the Scala, what did you have in mind?

When you first pitched the idea of making a documentary about the Scala, what did you have in mind?

AC: We did have an idea for a (with hindsight) quite pretentious, arty film – the hallmark of a debutante – called ‘An All Nighter at the Scala.’ It would be a portmanteau feature – five 20-minute-long films, to replicate the experience of a Scala all-nighter in miniature. Intertitles would flash up on the screen: ‘Sex’, ‘Drugs’, ‘Rock n Roll’. One of the films would be called ‘A Dream of the Scala’ (a very woozy, ambient one, replicating the experience of an All-Nighter). There’d be cutaways to the audience, drinking, shagging, whatever. I’m still a bit sad we didn’t do this – but budget dictates form. We didn’t have the money to stage this.

JG: We wanted to make a film which took the historical thread of the Scala story set against Thatcher’s Britain. We told the story through a kaleidoscopic mix of archive footage, movie clips, and new interviews with a very wide range of people who were in the audience at the time and went on to become filmmakers, musicians, writers, artists, actors, or activists.

What’s been the greatest surprise from audience reactions when Scala!!! has been shown at festivals?

AC: So many young people - and mostly young women, 24 and under (and several of them BAME) – have approached us after screenings to tell us how much the film has inspired them. Most of them weren’t even born when the Scala closed down. And yet something in the film (possibly because the Scala was run by a succession of young, strong-minded women) makes them want to go on to, at the very least, set up film clubs, or go into exhibition or distribution. It’s fantastic and gives the lie to the feeling that this film would only appeal to a bunch of old white blokes.

JG: In addition to the surprise of the younger women who’ve responded so strongly to our film, It’s a very emotional film which deals with loss. At a festival in Manchester a man came up to me after the screening to explain that he’d kept it together until he saw the image of the April 1993 Save Our Scala fundraising T-shirts for sale. Back in the day he’d bought one and then wore it to death over the next 30 years. He was weeping because he’d only just thrown away the rag which was once his Scala T-shirt, and the film bought it all back to him.

We asked lots of people to be interviewed for our film, and were always a little heartbroken when they either failed to respond or declined for whatever reason. But more important than this is those who did take the time and effort to participate and were such a joy to work with that made us all feel part of a disparate gang who’d reunited to celebrate the Scala cinema.

- Scala!!! plays at the Garden Cinema with Saskia Baron conducting a Q&A with Jane Giles and Ali Catteralll on Saturday January 6

- A season of films associated with the Scala runs at the BFI Southbank and on BFI Player

- Watch the trailer for Scala!!!! here

- More film reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment