Music from Sudan is overshadowed by the country’s recent history. At the end of June 1989, Colonel Omar al-Bashir assumed control and it became a one-party state. Shariah law was introduced. Osama Bin Laden was resident in capital city Khartoum from 1991 to 1996. Tension between the mostly Muslim north and mostly Christian south undermined any facade of stability al-Bashir sought to impose. The south was declared independent in 2011. Conflict in Darfur, in the west of the country, left 300,000 people dead and led to just over 3 million displaced people.

These are, of course, headlines. True understanding of Sudan’s difficult post-1956, post-colonial, post-independence history requires more than an outline. Nonetheless, it appears unseemly to unearth music made there in the 1990s and celebrate and enjoy it without experiencing some disquiet about the nature of the country in which it was made.

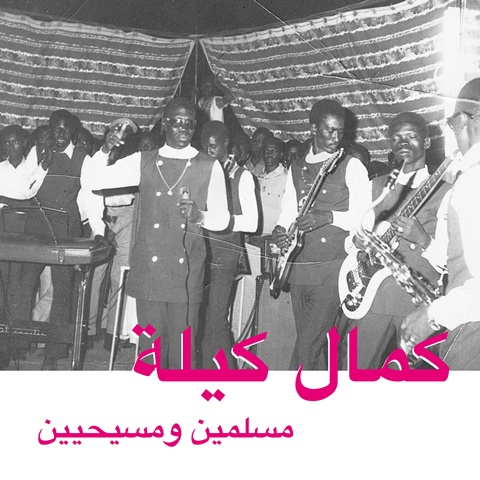

The waters are further muddied when the liner notes of the intriguing Muslims and Christians, a collection of previously unheard recordings by Kamal Keila, reveal he performed at al-Bashir’s request. Not that Keila had a choice. al-Bashir had ordered executions and imprisoned journalists. Such an invitation could not be refused. Before this, President Gaafar Nimery – ousted in a coup in 1985 – had taken Keila out of Uganda to perform in other African states. The ins and outs of what’s heard are head spinning.

The waters are further muddied when the liner notes of the intriguing Muslims and Christians, a collection of previously unheard recordings by Kamal Keila, reveal he performed at al-Bashir’s request. Not that Keila had a choice. al-Bashir had ordered executions and imprisoned journalists. Such an invitation could not be refused. Before this, President Gaafar Nimery – ousted in a coup in 1985 – had taken Keila out of Uganda to perform in other African states. The ins and outs of what’s heard are head spinning.

“When it comes to my style, my music is very political,” Keila is quoted as saying in the liner notes. “Art must talk about this. It is a message. It is not just for dancing and entertainment. There are lessons to give. Even the president of Sudan agreed with this. I travelled with him to the signing of the Peace Agreement in Nairobi. When the invitation came to the president, Omar al-Bashir, he asked: ‘Where is Kamal Keila? There is no other artist I can take’. He called me at 5am in the morning to travel with him. I collected all my band members and we went to the palace. We went all together [to Nairobi: the Nairobi Agreement was signed by Uganda’s President Museveni and al-Bashir on 8 December 1999] with the president.” Co-opted as Sudan’s musical ambassador, Keila was preaching messages conflicting with those of al-Bashir’s.

This music was meant to be heard by the whole of Sudan

It is mind boggling that Muslims and Christians exists. Its 10 tracks were recorded on 12 August 1992, close to ten years into Sudan's seemingly endless civil war – one which an estimated 2 million people ultimately died. The same five songs are repeated: first they are heard sung in English; then in Arabic – Sudan’s two languages. This music was meant to be heard by the whole population. The song “Muslims and Christians” has the lyric “some of us are Muslims, some of us are Christians, some of us live in the south, some of us live in the north…we are one nation, Sudan is one nation.” On “Agricultural Revolution”, he sings of needing an “agricultural revolution, so as to get a solution of hunger.” Hopeful words. Disunity and famine were familiar in Sudan. And indeed, very political. Unfortunately the liner notes do not explain how and why Keila was allowed to sing what he sang for the state-sanctioned national radio.

Kamal Keila grew up in Kassala, east Sudan and was born in January 1929. He formed his first band while at college in Khartoum during the Sixties. After studying law at Cairo University, he returned to Sudan and continued pursuing music while working as a lawyer. He has said that he liked blues, George Benson, Ray Charles, Sam Cooke and Elvis Presley, and that James Brown was an idol. His initial inspiration was Sudanese guitarist and jazz star Sharhabeel Ahmed.

Keila’s voice sounds like a grittier Lou Rawls

Although Keila was popular and regularly recorded for radio broadcast, no records or cassette albums have been found – an LP may have been issued, but copies haven’t surfaced. He recalls making a cassette album in Libya in 1976. What is heard on Muslims and Christians was recorded for the radio.

The astonishing context of these five songs threatens to overwhelm them: they could be artefacts freighted with meaning rather than music to be taken on its own merit. It is, however, immediately apparent that “Shmasha” (“Taban Ahwak” in Arabic: the Anglophone title refers to war orphans), “Muslims and Christians” (“Ghali Ghali Ya Jinub”), “Agricultural Revolution” (“Al Asafir”), “African Unity” (Ya Shaifni) and “Sudan in the Heart of Africa” (“Ajmal Alyam”) could fill dancefloors with people lacking any knowledge of what they are.

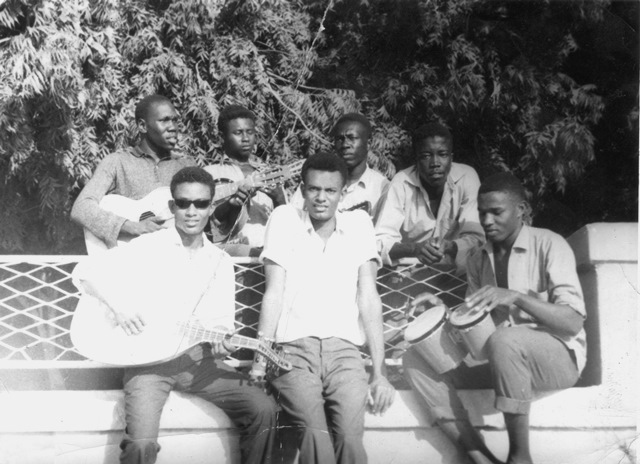

There are similarities with the known. “Agricultural Revolution” is, melodically, a lift from The Impressions’ “People Get Ready” and (doubtless unwittingly) Keila’s voice sounds like a grittier Lou Rawls. The stabbing brass suggests a familiarity with Sly and the Family Stone and the often-accented drumming nods to James Brown. (pictured left: Kamel Keila, front centre, and his band in the 1960s).

There are similarities with the known. “Agricultural Revolution” is, melodically, a lift from The Impressions’ “People Get Ready” and (doubtless unwittingly) Keila’s voice sounds like a grittier Lou Rawls. The stabbing brass suggests a familiarity with Sly and the Family Stone and the often-accented drumming nods to James Brown. (pictured left: Kamel Keila, front centre, and his band in the 1960s).

But other aspects of what Keila cooked up are more African than American. He opens “African Unity” by speaking the words “African’s our nationality”. His travels had taken him north to Egypt but to Ethiopia and Zaire as well as Uganda. His bands included Congolese musicians from the south of Sudan. The shuffling, almost-reggae, rhythm underpinning parts of “African Unity” are married with spiralling guitar maybe suggesting an origin in Mali, the Ivory Coast or Sierra Leone. “Sudan in the Heart of Africa” could be a stripped-down Nigerian recording. Everything sounds as if was taped in the first of the Seventies rather than 1992. When singing in English, Keila is proclamatory. When singing in Arabic, his voice softens and dances around the notes implying these versions of the songs were aimed at ears attuned to a style of music different to that created for Anglophone listeners.

If heard cold, the striking Muslims and Christians – despite mentions of “Khartoum town” and other local references – would not seem to be Sudanese or from the Nineties. Kamal Keila did not unite Africa but with his music he got as close as he could to achieving his goal.

- Next Week: 15th-anniversary reissue of Max Richter's The Blue Notebooks

Add comment