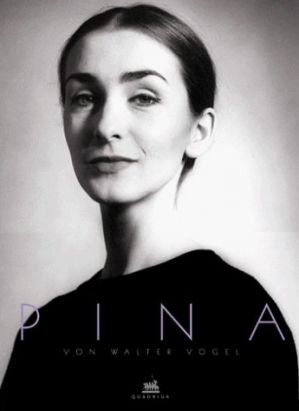

This week the world-renowned Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch arrives in London - for the first time, without its towering creator. Last summer the German choreographer died at the age of 68. The company intends to continue, despite the dodgy track record for troupes formed around one singular giant vision to survive long without that magnet at the core. Bausch (1940-2009) was shy in person and had no need to publicise her work, but at Christmas 2001 I met her in her base in Wuppertal, and she looked back in detail over the surprising sources in her life for her innovative style of dance-theatre. Small, grey, as unobtrusive as a wren, she seemed deceptively gentle and thin-skinned for someone whose theatre is legendarily acerbic, fantastical, sexually assertive and worldly in its wit.

Tanztheater Wuppertal HQ is in a side road in a vigorous commercial and industrial area of Wuppertal - a large, busy town with confident skyscrapers as well as a century-old monorail (the Schwebebahn, pictured below) which strides across town on gigantic Victorian (or Kaiserian) iron legs. Tanztheater Wuppertal is in the Altmarkt area, in the centre of things. Nothing drab or Slough-like about Wuppertal - this is more like Leeds.

Her assistant Sabine was more what I expected Bausch to be: a grey-faced, grey-clad, unsmiling personage who sat in the dark to work, smoking heavily, with the glow of a low desk-light the sole relief in an almost sinister fog of gloom. She was the kind of person you would want at your side if you wished to fend off publicity. She had no time for niceties or welcomes - barely grunted when I turned up at the office, having flown in from Britain. She sat firmly in on our interview, an attentive, silent monitor. She was entirely Bauschian - or Boschian.

Her assistant Sabine was more what I expected Bausch to be: a grey-faced, grey-clad, unsmiling personage who sat in the dark to work, smoking heavily, with the glow of a low desk-light the sole relief in an almost sinister fog of gloom. She was the kind of person you would want at your side if you wished to fend off publicity. She had no time for niceties or welcomes - barely grunted when I turned up at the office, having flown in from Britain. She sat firmly in on our interview, an attentive, silent monitor. She was entirely Bauschian - or Boschian.

Bausch herself was a willow twig by comparison, a wispy little woman of 61 with uncut grey hair in a thin ponytail falling almost to her waist. She wore black Chinese pyjamas. Her face was thin and troubled, yet she shyly smiled and suddenly kissed me when I offered her a carnation in greeting (referring to one of her best works, Nelken, set on a field of carnations). She was strangely girlish and little-old-ladyish at the same time. I imagined men would be drawn by her vulnerability, her Austenish sensibility that made her flinch at things she felt and things she saw around her - and put them into her sinister dances.

ISMENE BROWN: Can I ask about Wuppertal? You have been here so long - 27, 28 years? You were a local girl - originally from near here?

PINA BAUSCH: Yes, Solingen, very near, a city near by.

So since you had the whole world to go to, why here? Is there some magic?

No, no. it’s an accident. It just was that at a certain time the theatre director here insisted so much that I come here, and at first I didn’t want to go to a theatre - get into this kind of routine. I had a smaller company and I very much enjoyed that kind of work. But he insisted, and so I said, okay I will try. And it just happened that I am still here. [Smiles.] For maybe 20 years, or 25 years. I always had a one-year contract and was always ready to go. I would always be ready to go somewhere else. It was never meant that I stay here - it just happened.

So it wasn’t an emotional home for you?

Well, it got to be so, after so long. I like this area, I think it is very healthy to live in a weekday town - you know what I mean? I think it’s important to know certain realities where you work. And because we are travelling so much, also, which I like so much too, I think I have the best of both. It’s good to come back, it’s good to go.

I was curious about your sense of place and time. Having been born in Western Germany in 1940, and growing up in that war time and post-war time, I wondered if you grew up with a very strong sense of West and East.

I was curious about your sense of place and time. Having been born in Western Germany in 1940, and growing up in that war time and post-war time, I wondered if you grew up with a very strong sense of West and East.

No. I mean of course I was aware of it, but it was always quite far away, Berlin. Of course as a child, I was born in the war - that was already heavy! And unconsciously there probably is a lot of fear somehow, things you experience, feelings that you don’t understand. So... I didn’t see much. I mean, I went sometimes to the countryside near Frankfurt, for holidays with my parents, with my aunts or something, and it was far away. And I had never seen the sea. So the biggest change came then when I went to New York, of course, which was really fantastic.

When you were growing up, were you part of a large family?

I had a brother and a sister, and I am the, how do you say, “afterthought”. (Pictured, Philippine "Pina" Bausch in 1949)

The love child!

Probably. I’m the one my parents let do whatever I wanted. They were always very very busy, so I was always...

Left to yourself? To think freely for yourself?

Yes.

You address the subject of love so much in your dances - was your parents’ marriage a strong influence on the way you saw love? Were they a very loving couple, or a tough aggressive pair?

Oh... (pauses. laughs slightly and murmurs.) They loved each other very much. But it’s like, you experience all kinds of moods in life.

Did they shape your perception of relations between men and women - since it’s usually our parents who shape them?

But you know my parents had a restaurant, I was always in it. It was a neighbourhood restaurant, not like an elegant restaurant - but a place where life happens, and couples have love affairs and fights. Many people, I saw many people there, I don’t have to look at my parents. So it was a strong relationship in which anything can happen, from misunderstandings, to falling in love with other people, or losing work, all these sorts of things that maybe I didn’t understand, because I was little. But I was growing up in this kind of atmosphere.

Above, a fragment of Pina Bausch dancing in Café Müller (1978)

It’s almost a theatre of life! You were the audience.

Well, yes, and I was sometimes even involved, taking part. By caring.

That environment is a very exciting place to think of.

Yes, for me, very much.

All that food, smells, noise... you have a lot of eating in your pieces, don’t you!

[Laughs.] I don’t know. There are other people who have no café, and they also have food in their work. Food is something fantastic!

You don’t often see it in dance.

Well, I think it’s about all the things that grow, the smell - I think it is sinnlich, sensual, also. I enjoy my food!

You’re not one of these dancers with no appetite.

Oh, no!

You have a good appetite?

Yes! [Chuckles.]

For everything!

Yes! Hm-m-m-m!

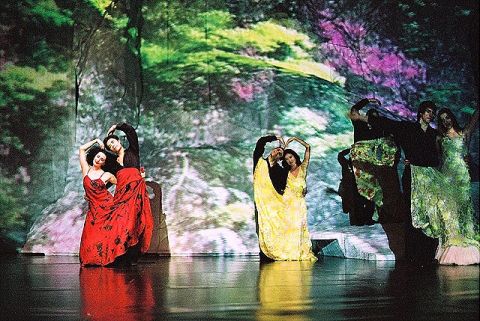

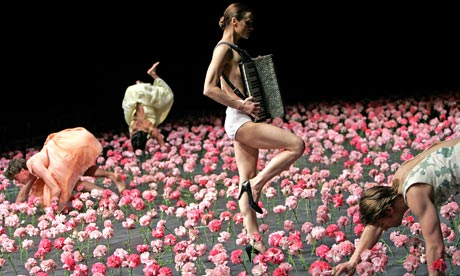

Above: Vollmond ('Full Moon'), pictured by Oliver Look

Of course you have put grass, earth, animals in the theatre - you seem to want to turn the theatre away from being an interior. Did you see some show that gave you that idea, or did you just want to break the rules?

No, I didn’t see that anywhere. It was just my wish to see that on stage. And to get the stage design, it was first Rolf Borzik [Bausch's partner, who died in 1980] and since 1980 Peter Pabst. I feel like certain things you put on stage make you look at them differently. They may be all around you every day, but they don’t mean anything. Suddenly you put them on stage and you take a new look at grass, or mosquitoes, or the noise you make when you walk - walking in water makes a different sort of movement from walking in leaves.

Sometimes things look dangerous but they are not dangerous at all. Some other things are very dangerous but don’t look dangerous at all

I like this sort of thing. And I like what it does to the dancers - it is a new experience that had an influence on your walk, your movement, your ideas also. And how you have to take care - like in Palermo Palermo the whole wall falls down and the stones are all over the stage, and if you walk among them in high heels, the way you have to handle the stage is not routine. It’s something very special. And I like to bring some reality, a form of reality, there. I like that very much - I’m looking for that. And also things I don’t know, I like to try out on stage.

I imagine that when you go on a picnic if you see a grassy hill, you want to roll down it. Your dancers react to the nature of the floor, the earth, the quality of it.

Yes, it’s completely different. And also you see, some people like earth, and the moment they start working on earth they go with their whole body, they love it - but others think, ooh, earth is dirty, and they are at first scared, ooh, I’m going to have to fall down in this. it’s wonderful for them to find that you can enjoy this - that it gives such a different feeling in your head and in your body. And that is what the dancers do a lot - it draws different things from them. It’s nice. Because there’s something like a child in all of us.

And they throw themselves around a lot, which can look quite dangerous, physically and emotionally too.

Oh [she purses her lips], sometimes things look dangerous but they are not dangerous at all. Some other things are very dangerous but don’t look dangerous at all. This is all a matter of how to work it, what to pay attention to.

What does the high-heeled shoe mean to you? It has been a strong feature in the dances of yours I’ve seen. Does it have a particular resonance to you, with that gathered party dress, very Fifties and pretty?

Oh...

Did you see this sort of clothing in the cafe?

No, they were not so elegant! [Laughs merrily.] They didn’t dress up like this, not at all. No... I like them, they look beautiful, that’s all. Also people now don’t dress up any more, me also, I don’t dress up. But on stage you can dress up, and I think it’s very beautiful, the way they walk, the way their legs look. I like colour, I like material, I enjoy that. It’s all that we don’t have outside here - in Wuppertal at least. Of course if you go to Paris or London, there is big big elegance. Here also there are elegant people, but you never see them - they must be going by car. [Laughs]

I was going to say: I wondered if you go out there in the street, see plainly dressed men and women and start imagining them in more colourful clothing and images.

I don’t know, I think maybe they too would like the joy to put a bit more pleasure in their life, and when they see something on the stage it inspires them, somehow. Like I did one production, Kontakthof, which I did with old people, gentlemen and ladies of more than 65, all people living in Wuppertal, amateurs. So we did the whole piece with them, and they were wonderful. And when they put on the costumes, at first it was “Oh no, it’s impossible to wear this”, but afterwards, having had the experience of doing this work, they changed absolutely - they all got younger, they became full of Lebenslust; they started buying colourful things.

So you’re good for Wuppertal shops too! People come out saying, “I must have colour”!

[Laughs.] I have no idea, but it was nice to see how they saw themselves, and their husbands or families or friends, and became so much more open. Even for young people.

Below, two versions of Kontakthof - upper, the young cast; lower, the older cast (photos by Laszlo Szito):

So you are saying you want to give people pleasure, and yet you also have this strange way of breaking people up too. When I see one of your pieces, half of me is saying this is so funny, the other side is saying, please don’t let this be the last thing I see before I die. Like Viktor. You get a combination of feelings of the lyrical and the grotesque. Also you have very good jokes. I like your jokes.

[Laughs.] Thank you very much.

Do you make them up? Or your dancers?

Well, nothing appears that I don’t want.

Do you write the text?

No, I don’t write a text. I don’t write anything.

What made you choose to go to New York?

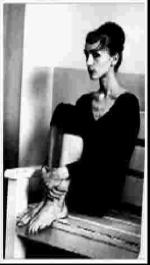

I was in Essen in the Folkwang school of Kurt Jooss [1901-1979, a pioneer of dance-theatre], and in the dance department the study course was of many different kinds of modern [dance], and ballet, and folklore, and composition and improvisation - many things. But what was interesting also at this time was that it was not only performing arts together but culture, painting, photography, design. All the arts together. It makes a big difference if you are with so many people working in different fields and not only in a dance studio. (Right, Bausch as a Folkwang student)

I was in Essen in the Folkwang school of Kurt Jooss [1901-1979, a pioneer of dance-theatre], and in the dance department the study course was of many different kinds of modern [dance], and ballet, and folklore, and composition and improvisation - many things. But what was interesting also at this time was that it was not only performing arts together but culture, painting, photography, design. All the arts together. It makes a big difference if you are with so many people working in different fields and not only in a dance studio. (Right, Bausch as a Folkwang student)

Anyway one day I saw a performance of the José Limon company, and I was thinking what I would do when I finished school I wanted to be a modern dancer - not because of any particular modern dance style but to express myself. I liked very much ballet also, but the performance by the Limon company impressed me so much that I decided I would study more. And Jooss actually brought many different and wonderful teachers from around the world - people from New York like Antony Tudor, Alwin Nikolais. So for me it was clear I wanted to know many more things about dance, and I got a scholarship for an academic exchange to New York.

In your time in the Juilliard School you trained with Margaret Craske, the Cecchetti ballet specialist. Did you find Cecchetti’s ideas interesting and influential?

It was very interesting: for modern dance the placement is different - the turnout, the way you stand. If you do all this modern work, standing on one leg, the supporting leg has a lot to do with it. (Below left, Bausch in ballet class in New York). But it was not only Craske, it was also Alfredo Corvino, who is still teaching here in the company, he is 84.

Cecchetti was so central to ballet in Britain, de Valois very much raised the Royal Ballet on him. I remember Lynn Seymour...

Cecchetti was so central to ballet in Britain, de Valois very much raised the Royal Ballet on him. I remember Lynn Seymour...

She was wonderful, absolutely wonderful. She has twins, no?

Yes.

They are so big now?

Yes. You like watching ballet?

Yes. sometimes. If somebody is doing it very beautifully, it is very beautiful. A good dancer is a good dancer whatever style.

For some minds it is very liberating to have so many different kinds of input, for some it is confusing. Did you always find yourself drawn to a mixture of all the arts, or did you have times when you wanted to go into a more pure form of dance?

I don’t know. Maybe it was something to do with the school; it was also to do with what Jooss tried to do. Always to give people a solid base, so that then you would know what you wanted, you could choose your direction. Also it helped me maybe to know what I felt, what I was longing for, where I was not satisfied, where I was reaching.

What kind of person were you at 18? In 1958 - that period in Germany. Was it a more optimistic time? Or did you need to get away from Germany to look back at it?

Hm... I don’t know. I think I didn’t know very much. I was always working very hard, and I only wanted to be a dancer. Not to be choreographer - I had no idea of that, never. My wish was only to dance. I found only that dancing was the way I expressed myself. I spoke very little then - now I talk like a waterfall! But then I had no words. And I found with music and with movement there was something that was me.

Which kind of movements spoke to you best? Did you ever feel tempted to specialise?

No. I liked many things. I liked ballet, even if my body is not as perfect as it should have been for a wonderful classical dancer, but I liked it very much. I liked so many different kinds of things.

What makes you laugh? Because you obviously do laugh!

Quite a lot. I like to laugh [she is slightly disconcerted by the question]. Anything. I think... I can be sad, I am full of fear, I am full of love, of a lot of tenderness, but I am also afraid of violence. And of course some of these things appear in the piece because I am afraid of violence. But what makes me laugh? It’s easy to make me laugh, I am like a child, very open.

Do you enjoy your reputation?

I don’t know what it is. Sometimes it is that I am a feminist, or it is that I’m always into relations between men and women - that’s not really true. It’s about relationships, but not always between men and women.

Do you think men and women will always fight? Will new eras change the way they relate?

Oh, they don’t only fight! [Laughs suggestively.] It has to do with the balance of it.

Sometimes the fighting is exciting too, isn’t it?

Sometimes the fighting is exciting too, isn’t it?

For some people certainly it is. Life would be boring without it. There are so many ways of relating to each other. (Right, Ein Stück von Pina Bausch, 2008)

When you say you are afraid of violence, is that something you picked up from being a child watching those people coming in and out of the cafe - was it a matter of individual violence, or was it a wider consciousness of national violence, growing up in post-war Germany with that post-Nazi history?

Mostly maybe that [she murmurs].

And has that feeling changed? Do you feel more optimistic now that the Berlin Wall is down and unification, for all its problems, is a positive thing.

Yes, that’s true of course, but still if somebody is screaming loud, I find it very uncomfortable. I can’t stay there and listen to it. If somebody is screaming, I feel my heart [she thumps her breast]. Everybody has their weak points ... [laughs a little].

Do you mean in terms of a man screaming violently at his girlfriend in the street or a political demonstration?

Anything. It depends, I suppose, on the kind of feeling in the event. A certain kind of aggression.

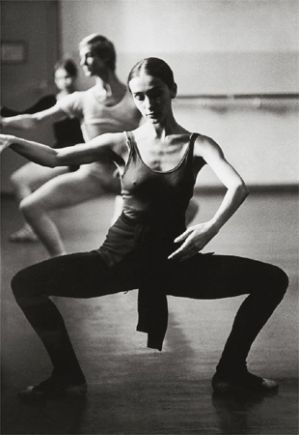

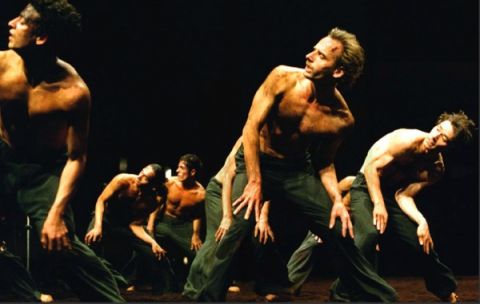

Above, an extract from Bausch's Rite of Spring

Did having a child change those fears, make them less or more?

Um, more, I think [a whisper, a sigh, a pause]... It’s difficult to say, because certain experiences about the world, how we look at what happens around us, changes us, so I don’t know whether without a child I would be different. You can’t tell whether having a child makes you see something that you might not have seen without one. But I mean we’ve forgotten about what happened to us when we were very little, but when you look at very young children you see how difficult life is for them, how serious their experiences are, the relationships, the fights at school, everything is happening that will happen to them in the future.

No, I am not optimistic. I think this is a very fragile time - in general, not here. Don’t you feel it?

But the fears should be less now - how old is your son? 21? When you were 21, in 1960, the fears you must have had about the world would reasonably have been far greater than he has now: the Soviet Union, the problems of Germany after the war.

Hmm... I didn’t maybe realise until much later. At this time I was in New York having an incredible time. I worked with the most fantastic teachers, I saw all the Balanchines, I was working with the Metropolitan Opera, I had so many possibilities - many people wanted to work with me. This kind of life was something very positive for me. Many things were coming together. So it didn’t look only negative to me. Of course, maybe the world situation was. But I realised much later, when I came back here, many more things than I realised when I was a child. Also in New York I learned a lot, just by living and seeing films that we had never and would never see in Germany.

But the Americans too were pretty ignorant of what was going on in Europe. Could you tell them anything about it?

No, what did I know? What could I show them? My ballet things? There was just me, and my experiences, and meeting a lot of wonderful people, from different nationalities, in New York. So it was a fantastic experience for me to be there, with who I was, what was possible, all these different types of people living together gave me a very positive view.

When you came back to Germany, did you find that your contemporaries, who had not been away, had a different kind of approach to your own? Perhaps less positive?

Well.... [pause] I can only see it from my own view. There were experiences where I felt that people abroad worked much much harder.

In America.

Yes. These companies that had no money, they all had normal jobs, they’d do this on the side. We had to work at nights, besides being at the Juilliard or Metropolitan. All these people doing so many different things, working so hard. Then I came here, and thought how comfortable people are here; they just do their things, go home. There were a lot of things I learned in America.

So that spirit of self-reliance, of can-do, would you say that’s still different?

I’m talking about that time.

Now of course it’s the other way round - the Americans envy the European model of subsidy for modern dance and art.

It’s very very complicated, difficult going round asking a little money here, a little money there, till you find enough to make something possible. Dancers often do this for love, because they want to, without any money.

You’ve done a few dances recently that are in a sense your impressions of different parts of the world that you’ve been to.

Influenced by [she corrects me]. It’s not like I’m taking something from them. Masurca Fogo is one of my co-productions, which I’ve done for a long time with different cities, different theatres. First time we did it was Viktor, with Rome and Argentina. Then there was Palermo Palermo. It was not like people gave the money to do the production, it was that the city was an influence on the work, so we would go there, being there, living there, working there for a little bit, so as to know as much as possible, experience certain things. It’s only a little, of course, but it gives me the impulse to know more, new doors open, things you didn’t know.

Are people all the same everywhere?

In a way they are all the same, but in many ways they are very different. Such as the climate, which makes a large difference. If you have people here when it is always raining, or somewhere where the sun is always shining, of course the way of behaviour is completely different - everything is outside, the cafés, the influence on the music. Of course the tradition and history, all this too. But still, I feel we are all the same really.

Masurca Fogo was a co-production with Lisbon. Portugal had of course very many colonies, and so I was very interested in the many different peoples there - a lot of people from Cape Verde, and they make incredible music, and also Brazil, which was a strong influence; and of course the sea. (Masurca Fogo pictured below)

We are always collecting music, wherever we go. I have two people who work closely with me as musical collaborators, Matthias Burkert and Andreas Eisenschneider, and they of course always want to be involved in the new work, so they are always looking out new music they know I will like. I get friends to bring me music, dancers bring me music. I have to hear everything, of course, it makes me crazy, but nobody can help me here - only I know where I am going in the piece, what the feeling is. When the piece is getting more shaped, then sometimes I may think, that bit of music is not really right. But I have a big help from everyone - it would not be possible otherwise.

We are always collecting music, wherever we go. I have two people who work closely with me as musical collaborators, Matthias Burkert and Andreas Eisenschneider, and they of course always want to be involved in the new work, so they are always looking out new music they know I will like. I get friends to bring me music, dancers bring me music. I have to hear everything, of course, it makes me crazy, but nobody can help me here - only I know where I am going in the piece, what the feeling is. When the piece is getting more shaped, then sometimes I may think, that bit of music is not really right. But I have a big help from everyone - it would not be possible otherwise.

If you did a piece about London, what would it be like?

Aha-ha-ha! [laughs] How can I say?

You’ve been there. What are your impressions?

I like that it’s so mixed - any big town is like that, a series of flashes that go by. But then what comes out is influenced by the dancers too, and it can go into a new direction you didn’t think of. I’m searching for that, always - to get what I am looking for - not something I know with my head exactly, but to find the right images. And I have no words for that. But I know right away when I’ve got it. If I say, it will be like this, it would limit it somehow. I like very much to be completely open, and allow things to happen.

I’ve read American critics who say you have an uncanny way of pinpointing the right things.

What is "uncanny"?

Supernatural, instinctive. The way you pinpoint California, for instance.

But that was also then, the time it was, or the way you wished it would be. The time is always open.

It’s a bit like the Grand Tour of the 19th century, when young men of wealth went out around Europe’s cities. I think this is rather fascinating to take dance to make something about a place. Character, yes, or events. But place?

Well, it is always about people.

You’ve become a sort of icon, a big influence in the theatre world. And on your web site I found five whole pages listing the theses and publications about your work. Yet you’re famous for saying that if it could be said in words, there would be no need for the work. How do you feel about all these words and analysis about your work?

Well, I don’t read this! [Laughs.] I sometimes would like to have the time, but in a way it would not be good for me either. It’s like pieces about me as an individual - well, it’s your meaning. For me, it’s important that the people who are there trust themselves, see what the images and music bring to them. Reaction has so much to do with each person’s life, what they see in what they see. It also depends on the day they go - it can be so different if you go to the performance when you just fell in love with somebody, or the opposite, or you feel ill. You experience the piece differently. And some people see something completely different from another.

Yet you seem to have started something. People now seem to need to know, analyse the meaning of it all. With Balanchine, Ashton, Graham, it was about story, culture, music, spectacle. But with your work, and perhaps particularly coming out of Germany after the war, people seem to want to understand the symbols of your work, and there is a whole culture of subtext now in dance theatre. Are people too complicated when they look at your work? It’s a bad influence, the words.

Yet you seem to have started something. People now seem to need to know, analyse the meaning of it all. With Balanchine, Ashton, Graham, it was about story, culture, music, spectacle. But with your work, and perhaps particularly coming out of Germany after the war, people seem to want to understand the symbols of your work, and there is a whole culture of subtext now in dance theatre. Are people too complicated when they look at your work? It’s a bad influence, the words.

I think there is another language we have altogether. Yes, that we understand each other.

Do Germans use much gesture? We don’t much in Britain. Do you think the amount people use their bodies to express themselves, makes them understand each other better?

Well, I’m sure it has a relationship; because there are countries in which it is very important to touch. Not just to make gestures, but to feel closeness. For instance, when I was working in Brazil, this was something I had never seen so strongly, such tenderness between couples, old couples, young couples. They like to touch, they like to be touched. I have never seen that anywhere else. It’s an extremely kind thing. And they have a nice way of talking together, their way of communicating.

You have used some of this in Masurca Fogo?

Not as I saw it, but of course it is unforgettable. And in this new piece, called Agua now, there are many things that were very strong, and I don’t forget, and they come into a piece maybe five years later. They stay in me, not forgotten, and they shape me in some way.

Like, it’s incredible how in Japan they don't touch. And yet there is such a special way of relationships. Without speaking or saying exactly how they feel, there is still some other kind of relationship which is very strong but had no words and no touch. And I think it is interesting that languages exists where the word "No" does not exist. I think it’s fantastic. You have to find another way to make the other person understand that it is not possible. But the word “No” doesn’t exist.

Where is that?

I think that is the case in India and Japan. And also “thank you” you don’t say in some languages. If you want to thank someone, you have to find another way. This is interesting. There are so many things I don’t understand that I just like. Like when I say “me” [she gestures at her breast], in Japan you say “me” [she touches her nose]. I just don’t know why, but I like it so much.

So this travelling thing is going to go on, to other places?

Yes, there are other plans. But what luck! With each thing you are able to learn again, have a new experience.

I noticed in Egypt that young men were very close, holding each other, and they loved my baby. In England men of that age would behave physically so totally differently.

As you say, you notice these things, and they puzzle you, and you love them. It is a very exciting subject.

Does it mean that you will look more outside at the rest of world to work, rather than explore the more private, internal German world that you explored in the past?

Of course, it’s like always... you are living now in this time, and this situation. I am not optimistic. I think this is a very fragile time - in general, not just here. Don’t you feel it?

Do you think the time is better? Are you optimistic?

No, I am not optimistic. I think this is a very fragile time - in general, not here. Don’t you feel it? I feel you don’t know where the world is going, how to do things, what is right, what to think. It’s difficult. (Below, 'Nelken', picture by Tristram Kenton/Sadler's Wells)

But from the outside circumstances look happier - none of these great divisions that used to exist between East and West, for which many people were murdered.

No - for human beings, yes, I am optimistic. I have a lot of luck and such fantastic experiences all the time. And people let me share so much of their lives, with so much trust. And I’ve seen so much beauty. I have so much respect from so many people, and I feel the same about them. That is wonderful. But the politics, the world politic - where we have no influence, that frightens me.

My personal view of human beings I will not cease looking for this friendship, to share, and I have received also so many things that I must spend another lifetime giving back to them the trust and beauty and art that I had from them.

Whose art inspires you?

To do a piece, nobody can help me [laughs]. It’s only life that can help you.

Yes, but are there people whose work really you love?

There are wonderful artists in the world, so many in so many fields; film, and music, everywhere, it’s wonderful how rich it is, and of course this gives you strength, because you know so many people are working sincerely on something. But it would be unfair to pick out people.

In every dance, is there a person who is a ghost of you, in a sense? There is often one particular person that an artist has a particular sense and preference for...

Yes, but my dancers are all so completely different from each other. Each one. I don’t know if they are an extension of me, or I am an extension of them. I’ve always kept learning about myself because of that. Before, I always thought, okay, that’s about me and what I feel. But actually you experience, by working with other people, so many things you would not yourself have thought.

It’s a huge number of people to control - 30, 31 in every piece.

It’s a huge number of people to control - 30, 31 in every piece.

I have different numbers sometimes 18, 24, 26, but they all want to be in it! They’re not just coming for fun to Wuppertal. (Left, 'Sacre du Printemps' pictured by Ursula Kaufman)

Do they get distressed if you don’t use them?

Of course. Sometimes. That’s life. They easily think they are not liked [she purses her lips]. It’s normal.

Have you thought you might just do a very small piece?

My next piece might be a very small piece, but it’s a bit difficult to do that. In my own way I want it very small, but then I also know that makes a problem with certain people - so I try to just have it as small as possible.

But with a large company you are under a certain pressure to come up with company pieces - how free are you?

I am still free, but I want them all, I love them all, and I want them all to be happy with their work. I also have the complications and richness of all these personalities. It’s an enormous chance to do something with all these people - that it is difficult is only secondary. It grew like this.

How long do you see it continuing? Cunningham has never stopped; but sometimes people have another desire, another life in mind.

I’m so lucky in this profession, because it’s not just about dance - it’s all about music, beautiful music which I like, the stage, the picture that I can paint, what they wear, the text I can use, the relationship with the public. So many things come together in this, not just dance. The basic point is the dance, but all these other things too - what could be better?

- Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch perform both versions of Kontakthof at the Barbican Theatre Thursday-Sunday 1-4 April. There is also a concurrent Barbican season of documentaries and the 1985 film of Café Müller.

- Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch performs the Brazil-inspired Agua in the Edinburgh Festival (27-29 August, Playhouse)

- The company's web site

- Check out what's on at the Barbican this season

- Bausch's Café Müller features in Pedro Almodovar's film Talk To Her

- Bausch's choreographed version of Gluck's Orpheus and Eurydice is a rare DVD of the company

- Wim Wenders is currently shooting Pina, a 3D film of her dances

Add comment