Interview: Rokia Traoré | reviews, news & interviews

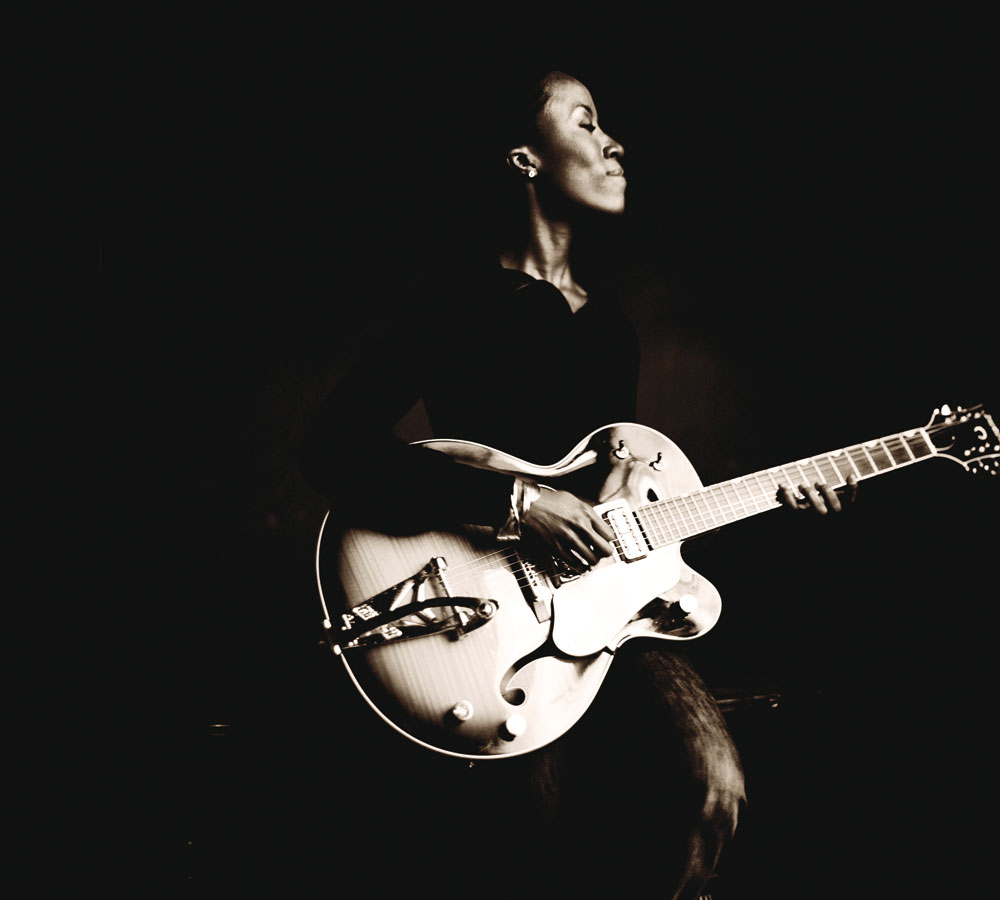

Interview: Rokia Traoré

Interview: Rokia Traoré

Malian singer-songwriter on escaping the 'jail' of world music

Rokia Traoré has always seemed most comfortable creating at trysting points, darting between different worlds without ever quite belonging to any one of them. The daughter of a Malian diplomat, as a child her favourite locations were airports, “this middle point between two places; the idea of leaving a place to go to another one was the most interesting part of my childhood”.

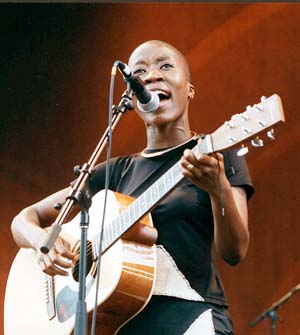

Traoré, who released her fourth album, Tchamantché, in 2008 and starts a UK tour tonight, is in many respects an anomalous Malian musician. A thoroughly modern songwriter who plays acoustic guitar and writes and arranges her own material, she draws influences from all over the landscape. When Traoré sings in Bambara, her native tongue, it isn't to try to fit in to some accepted cultural lineage; rather, it's to make the point that modern, progressive music can have an African voice. Unwilling to tether herself to accepted notions of what her music can and can't be, she memorably ended Tchamantché with a cavalier English-language cover of Gershwin’s "The Man I Love". She doesn’t have – nor does she seek – any claims on tradition.

She came to music via an unconventional route, following her family around the world and back, from Brussels to Israel, Algeria to Saudi Arabia. In the artificial confines of gated diplomatic quarters and international schools she soaked up Brel, Gainsbourg, Miles Davis, classical, rock and reggae, and from an early age cultivated the instincts of an outsider.

“Of course it was difficult to make friends because you are moving all the time, but also because you never feel exactly like the people you meet in any specific place,” she says, speaking on the phone from a hotel room on America’s eastern seaboard. “I loved to try to know about ordinary people, but it was very closed and I felt very different, I couldn’t really discuss the same things with them. I think I’m still like that. I’m not someone easy to get to know. I don’t know if that’s because I travelled a lot as a child or if it’s part of my natural personality. I’m very nice! I’m a very pleasant person, I don’t like to make people feel bad, but there are not so many people I appreciate being with and spending time with, and it’s the same in the music area.”

With her relative privilege came another kind of struggle. Traoré is not a griot, the proud bloodline of West African poets and troubadours that keeps the heart of Malian culture pumping, nor is she from a traditional musical background. When it came to pursuing her passions she found she lacked a foothold in the culture around her. “In Mali there are some specific places to learn music – griot areas, national orchestras – but I came from nowhere,” she says. “It wasn’t as easy as the musicians who knew each other and came from the same schools or systems. They knew who was who. I was very different. I always wanted to be a musician but I didn’t know if it would be possible. It was a kind of secret will I kept for years.”

In high school she joined a rap band, and around the same time began working in a radio station. The listeners would call in during the show admiring her speaking voice (which is indeed a lovely thing: mellifluous and musical, pitched just above a whisper yet clear and strong) and asking whether she also sang. “I started to think, ‘Why not?’ I played guitar at home and I used to write my lyrics, and step-by-step I arrived at this TV show where I performed two songs. People really loved my songs, because they were different from what they normally heard in Mali.”  Her rapid success, aided by the patronage of Ali Farka Toure, proved an eloquent rebuttal to the many traditional musicians who regarded her with a mixture of scepticism and suspicion. “I wasn’t supposed to be someone who had a long career,” she says. “Some of them told me that, and I also heard about it. They thought I would disappear very quickly. I never felt angry, because it’s a very natural, very human reflex, not to understand someone who is so different.”

Her rapid success, aided by the patronage of Ali Farka Toure, proved an eloquent rebuttal to the many traditional musicians who regarded her with a mixture of scepticism and suspicion. “I wasn’t supposed to be someone who had a long career,” she says. “Some of them told me that, and I also heard about it. They thought I would disappear very quickly. I never felt angry, because it’s a very natural, very human reflex, not to understand someone who is so different.”

Her debut album, Mouneïssa, sold 40,000 copies in Europe on its release in 1998. She was 23 and “had no idea what it meant to sell more than 40,000 albums! I said, ‘Is that good?’ and I was told, ‘Yes, it’s more than good for the first album from somebody who is totally unknown’. I had no idea! For a long time I did things just with my heart, with no ambition to sell albums.”

Traoré has now been singing professionally for 13 years, and has harvested her fair share of honours: a BBC Three World Music Award; the Victoires De La Musique for Tchamantché. She has used wisely the perception that she is an outsider, paying scant heed to what African music is meant to be and instead forging her own path, ensuring each of her four albums is markedly different in tone and texture. With each one she has emphasised that she is not a singer in the Malian tradition. “That doesn’t mean I don’t appreciate the musicians from Mali,” she adds. “I listen and appreciate, but we can’t even have a discussion. We have so many different opinions and ideas that there is no way to understand each other! We are like from two different planets, even though we are from the same country.”

In December 2006 she performed a new piece, Wati, with the Klangforum Wien at Peter Sellars’ New Crowned Hope Festival, part of the 250th anniversary of Mozart's birthday. She says that working with Sellars “gave me the opportunity to get out of world music. I can’t breathe in world music, it’s a kind of jail. It’s too small and it’s too big, also. It includes so many styles of music from all around the world, and there are too many things in a small place. That wasn’t my idea of music when I started listening as a child. To me, music is freedom. There’s some wonderful music in world music, but the concept is really small, and I can’t stay in that.”

She has some interesting, perhaps somewhat off-message things to say, too, about the reality of what is widely regarded as a boom time for music from the African continent in general, and Mali in particular. The current is flowing only one way, she says bluntly. European musicians cherry-pick ideas from African counterparts, who are all too eager to seize the chance for western exposure, but she sees little evidence of African musicians taking the imitative and incorporating European influences into their own music.

There is, she says, “something wrong in the relationship, I can’t quite explain it. I don’t feel comfortable with the fact that in general collaborations between African and European music depends on Europeans musicians. It’s an opportunity for African musicians to develop their careers in Europe, but I don’t know how beneficial that is for African music. It’s something good for the African artist for a short time, but it’s time to push the African musicians with their own talent, not for collaborations with European musicians.”  If this sounds a little aloof and dismissive, I suspect it isn’t meant to. Traoré is aware of the many difficulties inherent in African musicians maintaining a career in their own continent, partly due to “economic considerations – there’s no real industry and structure”, and she recognises that she is speaking from a position of relative privilege. “Many African musicians need money, and even if they love music, their choices are motivated by how much money they will get from a project, not if they will love it,” she says. “I had a chance not to have this problem. Money has never been my first motivation. I’m not like someone who suffered very much and money is important very early.”

If this sounds a little aloof and dismissive, I suspect it isn’t meant to. Traoré is aware of the many difficulties inherent in African musicians maintaining a career in their own continent, partly due to “economic considerations – there’s no real industry and structure”, and she recognises that she is speaking from a position of relative privilege. “Many African musicians need money, and even if they love music, their choices are motivated by how much money they will get from a project, not if they will love it,” she says. “I had a chance not to have this problem. Money has never been my first motivation. I’m not like someone who suffered very much and money is important very early.”

Aware of the need for some additional infrastructure, Traoré formed the Fondation Passerelle (passerelle being French for "footbridge" – another symbol of Traoré’s preference for making her home at crossing points), to help young Malians build careers in the music business. “I don’t think with one foundation I’m going to change things, but it’s my contribution and it’s very important for me to give it,” she says. “My work makes me speak all the time about African music, and I’d like to be able to say what I do as well as what I think. It won’t work 100 per cent, but we are trying.”

The Fondation Passerelle has strengthened this happily peripatetic woman’s roots in her native country. She lives “half-half”, dividing her time between her home in Amiens in northern France and her newly constructed house in Bamako, which doubles as a rehearsal space and an ad hoc musical community centre. “My house is a kind of story,” she laughs. “There are so many things happening there now.” Her husband and manager is a Frenchman, and her four-year-old son “has the same thing as his mum already. He can’t stay in one place too long. When he stays more than two months in Mali he wants to move to France; and when he’s in France too long he’s asking to go back to Bamako.”

As a recording artist, Traoré has never been terribly prolific: just four albums in 12 years, with the gaps widening. She plans to start work on a new record at the end of the summer, but can’t see a release before 2012 because “between records there are so many interesting things to do”. Next year she will work with Peter Sellars again, this time in conjunction with Toni Morrison, who has written a play to be performed by two women, one singing and the other acting. Sellars will direct. She will also be heavily involved with the children's choir she has helped put together in Bamako, which will shortly be giving its first concert and then going on tour. “They will need me for a while to be there,” she says with a maternal sigh.

Before all that, she embarks on a seven-date UK tour with Sweet Billy Pilgrim, the experimental English three-piece who record their music in a garden shed with one microphone and a lap-top. It's another left turn, another get-out-of-jail pass. She and the band exchanged ideas via email while Traoré was touring America, and will be sharing the stage for at least one unique collaboration during their jaunt around the country.

The tour was put together at Traoré’s suggestion, and she sees performing with a British rock band as “another kind of escape. It seems very natural to me, it’s just the way I see music. Maybe I was naïve when I started, but I want to keep that idea that everything is possible".

- Rokia Traore and Sweet Billy Pilgrim play Koko, London tonight and then tour until May 7

- Find Tchamantché on Amazon

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Trio Da Kali, Milton Court review - Mali masters make the ancient new

Three supreme musicians from Bamako in transcendent mood

Trio Da Kali, Milton Court review - Mali masters make the ancient new

Three supreme musicians from Bamako in transcendent mood

Hollie Cook's 'Shy Girl' isn't heavyweight but has a summery reggae lilt

Tropical-tinted downtempo pop that's likeable if uneventful

Hollie Cook's 'Shy Girl' isn't heavyweight but has a summery reggae lilt

Tropical-tinted downtempo pop that's likeable if uneventful

Pop Will Eat Itself's 'Delete Everything' is noisy but patchy

Despite unlovely production, the Eighties/Nineties unit retain rowdy ebullience

Pop Will Eat Itself's 'Delete Everything' is noisy but patchy

Despite unlovely production, the Eighties/Nineties unit retain rowdy ebullience

Add comment