Anselm Kiefer: Il Mistero delle Cattedrali, White Cube Bermondsey | reviews, news & interviews

Anselm Kiefer: Il Mistero delle Cattedrali, White Cube Bermondsey

Anselm Kiefer: Il Mistero delle Cattedrali, White Cube Bermondsey

A giant among the pygmies of contemporary art

That Anselm Kiefer is one of the great elder statesmen of contemporary art goes without saying. His work’s precise relevance to now is less clear. In the early 1980s, when he sprang to fame as part of the New Image Painting phenomenon (with Schnabel, Baselitz et al), the Berlin Wall was still up and the post-Holocaust Teutonic angst that Kiefer has relentlessly mined felt far more immediate and problematic than it does today. The great Monetarist showbiz-art wave hadn’t yet broken.

Lead books, desiccated sunflowers, sumptuously ravaged painterly textures, and a set of political, literary and mystical preoccupations that alternate but don’t really change: when you go to a Kiefer show you’ve got a fair idea of what you’re going to get. And for anyone wanting the Kiefer’s Greatest Hits experience, this biggest British show to date – held in White Cube’s magnificent new Bermondsey space – won’t disappoint. With pieces from as far back as 1988 dotted among large-scale current works, the exhibition works as a kind of summation of his career to date.

The first room displays both the strengths and weaknesses of the Kiefer approach. Fulcanelli finis gloriae mundi, a gigantic bunch of paint and plaster-stained sunflowers shoved into an oxidised lead plane wing, and Dat rosa miel apibus (pictured above), a great stack of lead books with small planes poking from between their rusting leaves, are pretty much what you’d expect to find here, but executed with exhilarating bravura and the feel for atrophic texture that is one of the most rewarding aspects of Kiefer’s work.

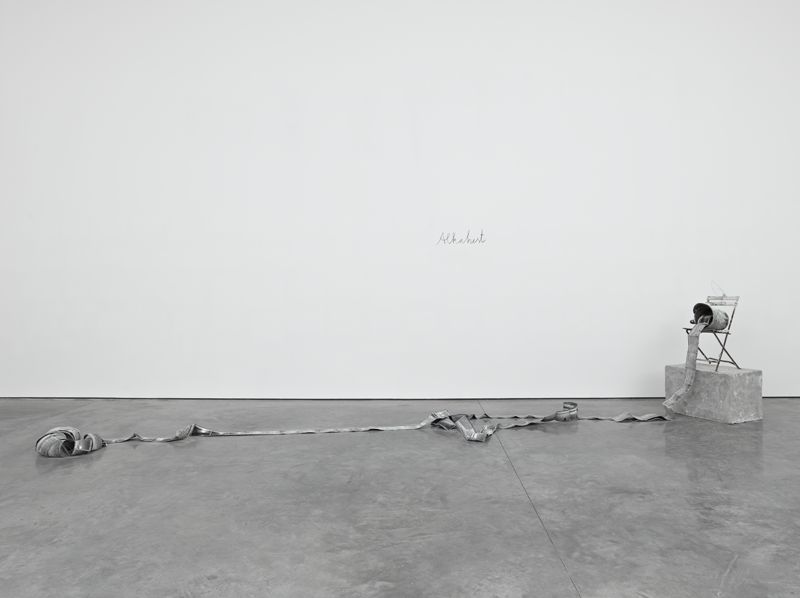

Alkahest (pictured above), a stream of lead-fringed photographs of changing light on a beach spilling from a heavily oxidised lead bucket, refers to the exhibition’s title theme – The Mystery of the Cathedrals – taken from a 1926 treatise by esoteric writer Fulcanelli, claiming that the secrets of alchemy are revealed in the structures of medieval cathedrals. If this notion is relatively little explored in the show as a whole (probably mercifully) the piece works as an embodiment of "the hastening of time", which Kiefer considers the essence of alchemy, precisely because the heavy-handed symbolism - his great weakness - isn’t made explicit.

Alkahest (pictured above), a stream of lead-fringed photographs of changing light on a beach spilling from a heavily oxidised lead bucket, refers to the exhibition’s title theme – The Mystery of the Cathedrals – taken from a 1926 treatise by esoteric writer Fulcanelli, claiming that the secrets of alchemy are revealed in the structures of medieval cathedrals. If this notion is relatively little explored in the show as a whole (probably mercifully) the piece works as an embodiment of "the hastening of time", which Kiefer considers the essence of alchemy, precisely because the heavy-handed symbolism - his great weakness - isn’t made explicit.

Merkaba, on the other hand, a crudely fashioned tandem trike referencing the cabbalistic Chariot of God, hung with measuring trays of chemical elements – sulphur, sodium and mercury – leaves you feeling that the exploration of the metaphysical properties of materials was done in a more resonant, less literal way by Kiefer’s mentor Joseph Beuys.

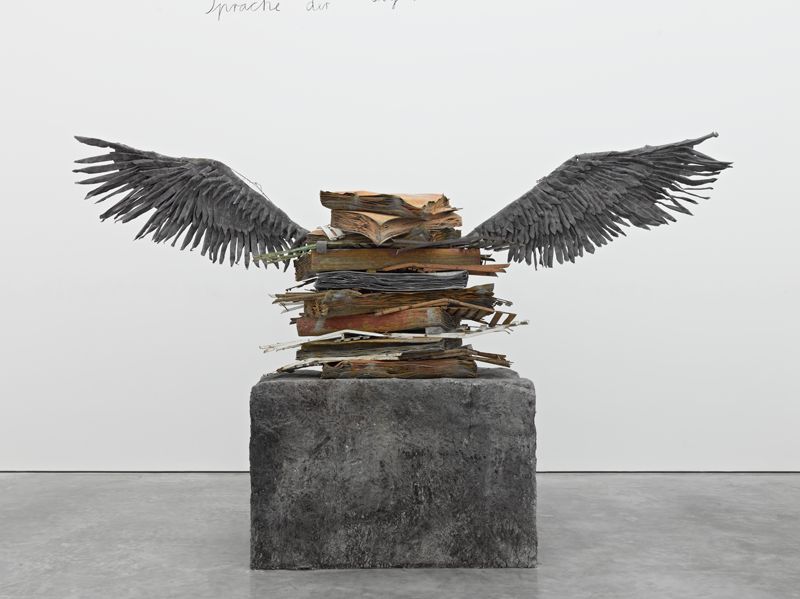

Faced with Sprache der vögel, from 1989 (pictured above), a stack of lead tomes and folding chairs, looming over the small second room, sprouting lead wings (eagle’s of course) and set atop a massive block of ash-encrusted resin, you feel unsure whether to applaud or howl with derision at his bombastic effrontery. Teutonic mythology and cultural guilt elide in a megalomanic gesture that now feels slightly glib.

Entering the first of two rooms inspired by Berlin’s now defunct Tempelhof airport, built in the 1920s on land once owned by the Knights Templer and refashioned by Albert Speer, the symbolism feels at first almost painfully obvious: a massive pair of rusting dividers hanging across a canvas splurged with oxidising salt and iron, a satellite dish, a pair of scales dangling on a clunkily painted mountain landscape. Invoking big themes and time-honoured symbols is no guarantee of profundity.

Kiefer's mastery of mood, space and texture bludgeons down your reservations

This, however, is merely an antechamber to a second room whose sheer scale and ambition knock you sideways. Enormous paintings of the airport’s curving exterior and long vistas of the interior face each other across the vast floor. Revisiting sites of guilt in images created by scoring into thickly impastoed paint is something Kiefer has been doing since the mid-Eighties. In essence there’s nothing new here. Indeed, with works dating from the late 1980s till now dotting the floor, you may well actually have seen some of this stuff before. Yet if there are details to take issue with just about everywhere you look, the overall mastery of mood, space and texture bludgeons down your reservations.

Size isn’t everything, but the widescreen breadth of the painting confronting you on the far wall, Dat rosa miel apibus (reprising a title from the first room), is jaw-dropping: a 56ft-long perspective view of one of the airport’s corridors, executed in a devastated morass of salt, oxidised lead, resin and gouged and cracked oil paint, with an inverted bouquet of blackened sunflowers, some 12ft in length, hanging at the centre. This is hardly painting in the generally understood sense: it’s difficult to imagine the work meaning much on its own. But as part of the overall installation, hitting off the paintings on the other three walls and the three-dimensional pieces in the foreground, the effect is extremely powerful.

Yet even here, elements of overcooked theatricality intrude: a clay snake writhes among the battered sunflowers of Nigredo, echoing the serpent crawling up the resin plinth of the egglike Opus magnum – a work that magisterially echoes Brancusi, while betraying not a hint of irony in its title. Templers, Nazis, alchemy, Jewish mysticism, Norse gods: Kiefer brings together a raft of portentous elements that would give even Dan Brown pause for thought. Sometimes you wish he would give his forms, materials and textures more space to speak for themselves rather than relentlessly hammering them with mythic content. Still, this is a mind-bending show that must be seen. It leaves you with the sense of an artist who, for all his faults, is a giant among the pygmies of contemporary art.

- Il mistero delle cattedrali is at White Cube Bermondsey till 26 February

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Comments

the overbearing imagery just