Matthew Bourne's Play Without Words, Sadler's Wells | reviews, news & interviews

Matthew Bourne's Play Without Words, Sadler's Wells

Matthew Bourne's Play Without Words, Sadler's Wells

Bourne's masterpiece - a giddy, sexy, diabolical confection that deserves to become a global smash

Sound the trumpets triumphantly - Matthew Bourne’s most original masterpiece has come out of hiding into full view, a giddy, sexy, diabolical confection that hovers on the edge of hellish, and deserves to become a global smash.

Bourne made the work in a National Theatre workshop 10 years ago, and that experimental milieu drew out of him a concept of amazing boldness and a perfect execution. One can cite any number of source references in it, from Joseph Losey and Joe Orton to Shakespeare, and yet something bitingly Bourne-ish bounces up clean and original through the welter of clever derivations. A scenario of familiar subversiveness is set in 1960s Belgravia where the upstairs masters are taken apart by the downstairs servants, sexually, morally and culturally. But as it’s told in dance, you derive a sophisticated, ambivalent subtext that takes the entire piece to the level of an existential essay on free will.

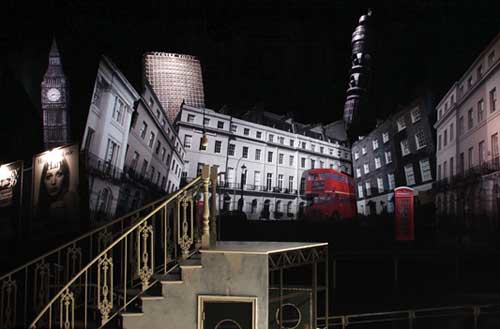

Lez Brotherston created for it one of his most evocative sets, where white Belgravia lurches behind a red bus and a scarlet phone box, where a mobile white staircase doubles as the entrance into a spacious drawing room, where black railings outside indicate a public gents’ lav, the scene only needing Sergeant Dixon to amble by. The eye-view is tellingly dislocated, so that you are looking from below the street level.

Lez Brotherston created for it one of his most evocative sets, where white Belgravia lurches behind a red bus and a scarlet phone box, where a mobile white staircase doubles as the entrance into a spacious drawing room, where black railings outside indicate a public gents’ lav, the scene only needing Sergeant Dixon to amble by. The eye-view is tellingly dislocated, so that you are looking from below the street level.

And in that street, as the piece opens, a wild jazzman is disturbing the SW1 peace with his trumpet, a louche man with no tie and a red checked shirt, who will play a role somewhere between Puck, the imp of sexual mischief, and Lucifer, the lord of damnation, mixing up classes, genders, rules, definitions, leaving only debris and broken men behind.

He is Speight, listed as “an old friend”, the only character to be played by a single actor - all the others are triplicated and duplicated, a genius device, because they’re going to be smashed up. (Whose “old friend” is he? You wonder.) He’s also the spirit of the music that lures the revels on, a deeply delicious creation by Terry Davies that marries late-night jazz clubs to Bach and Caribbean voodoo beats.

Which is saucier? When the servant undresses his master, or when he dresses him? These happen in parallel, and crumbs, it’s eye-opening

The occupants of the house are upper-class Anthony, his manservant Prentice, his elegant fiancée Glenda and the new housemaid Sheila. Three Anthonies, in their beige suits and horn-rimmed specs, three Glendas, in chignons and tight oatmeal suits, three Prentices in navy valet aprons, two sexy Sheilas, the housemaid, who has stepped straight in from an Italian movie with full red lips and a too-short skirt.

All the different versions are frequently on stage at once, but not milling about, not in the least - each pairing has its own distinct trajectory. Like people in crowds, they know where they’re going, and to whom. And because each of the versions is doing something slightly different with the same situation, you see a multiplicity of possibilities, the constant shifting of options and choices available, amorality on a plate, having it all ways.

Sometimes it’s pure naughtiness. For instance, which is saucier? When the servant fastidiously undresses his master, or when he dresses him? These happen in parallel, and crumbs, it’s eye-opening. Even more so is the quite extraordinarily hot seduction on the kitchen table by Sheila of her master, wearing his cricket sweater over her brief black knickers, an affair that in dance language homes in with laser eroticism onto fingers, toes, sudden tiny, hair-prickling touches - and then explodes with open legs and whirling acrobatic lifts.

And yet Bourne is also so good at cool: his performers are actors as much as dancers, and his three Prentice actors keep a masterly poker-face in their servant activities, literally - and hilariously - anticipating their masters' every move, and breaking almost with relief into sneers and wrenches when the gloves come off.

And yet Bourne is also so good at cool: his performers are actors as much as dancers, and his three Prentice actors keep a masterly poker-face in their servant activities, literally - and hilariously - anticipating their masters' every move, and breaking almost with relief into sneers and wrenches when the gloves come off.

The Anthonies, the masters, have a trickier challenge to summon sympathy from inside their hooray-Henry exterior, and they need to avoid playing clichés to the gallery (particularly Richard Winsor last night, who could rein it in). The outstandingly contrasted trio of performers is the Glendas who each present a different set of needs, haughty Saranne Curtin, an arrogant smile around her lips, the sensual, submissive Anjali Mehra, Madelaine Brennan, who you sense deserves better (pictured, Glendas and Anthonies, in parallel flirtations). By contrast again, the Sheilas are brilliantly identical, Anabel Kutay with her Nefertiti profile and sloe-eyed Hannah Vassallo, exquisitely sex-kittenish with their dark Italian hair and bare, tanned legs. The minutely plotted samenesses here and differences there are little switches exactly applied to turn Belgravia into Lord of the Flies.

Its intricacy of use of the stage could never be filmed, it is pure live stage entertainment of the highest order

Swarthy Jonathan Olivier as Speight is as explosive as Elvis, the spirit of the Sixties - yes, it does sound over-familiar, but he’s a package of Stanley Kowalski, Mephistopheles and even Petrushka as well, every racy, exciting, rule-breaking adolescent, every evil social terrorist, but also - and this is why it's clever - every confused boy lashing out to liberate his personal identity.

This is just tremendous theatre, dance, dance-theatre, its innovativeness thrown into keen perspective by the Pina Bausch season just gone, which repeated tropes over and over. And another bonus is that it so completely is bound to the wooden boards of the theatre - its intricacy of use of the stage could never be filmed in any way, it is pure live stage entertainment of the highest order.

This year we’ve seen a 25-year retrospective of the Bourne identity, from his earliest amuse-bouches and the poignantly rewarding Swan Lake that the world has embraced, with a new Sleeping Beauty to come this winter. Most of his work in the past has derived from other sources. Play Without Words, despite its looking back to Joseph Losey and John Osborne, shows something more remarkable still, total individuality, total originality, a unique mastery of theatre. You have three weeks to get to it - run, don't walk.

Matthew Bourne's trailer for the revival of Play Without Words

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Add comment