Still waters run deep, but that truism barely hints at the quiet power of The River, the eagerly awaited new play from Jez Butterworth (writer) and Ian Rickson (director) whose collaboration yet again gives cause for cheer. The converse in almost every way from their immediate Royal Court predecessor, Jerusalem (2009), this latest work is as small-scale, intimate, and compressed as that epoch-defining transfer to the West End and Broadway was rangy, anarchic, and feral.

Don't let the fuss about how to get tickets - there is no advance purchase possible, only day seats - put you off the quest to do so. Here's a puzzle play, alluring and unsettling in turn, that puts one in mind of a roll call of writers (Harold Pinter among them) in different ways while marking Butterworth out anew as the most singular voice in town.

The affinities to Pinter would be evident even without the Nobel laureate's widow, Lady Antonia Fraser, seated in the front row on opening night. At once sexy and sorrowful, its quotidian exchanges flecked with shards of poetry that give way to full-flown arias on such topics as the survival tactics of trout, this play's cunning begins with our first glimpse of a set that would seem to be the last word in naturalism. (The designer, as with Jerusalem, is Ultz, working here with a rural interior as against a roof-scraping Wiltshire mini-forest.)

The affinities to Pinter would be evident even without the Nobel laureate's widow, Lady Antonia Fraser, seated in the front row on opening night. At once sexy and sorrowful, its quotidian exchanges flecked with shards of poetry that give way to full-flown arias on such topics as the survival tactics of trout, this play's cunning begins with our first glimpse of a set that would seem to be the last word in naturalism. (The designer, as with Jerusalem, is Ultz, working here with a rural interior as against a roof-scraping Wiltshire mini-forest.)

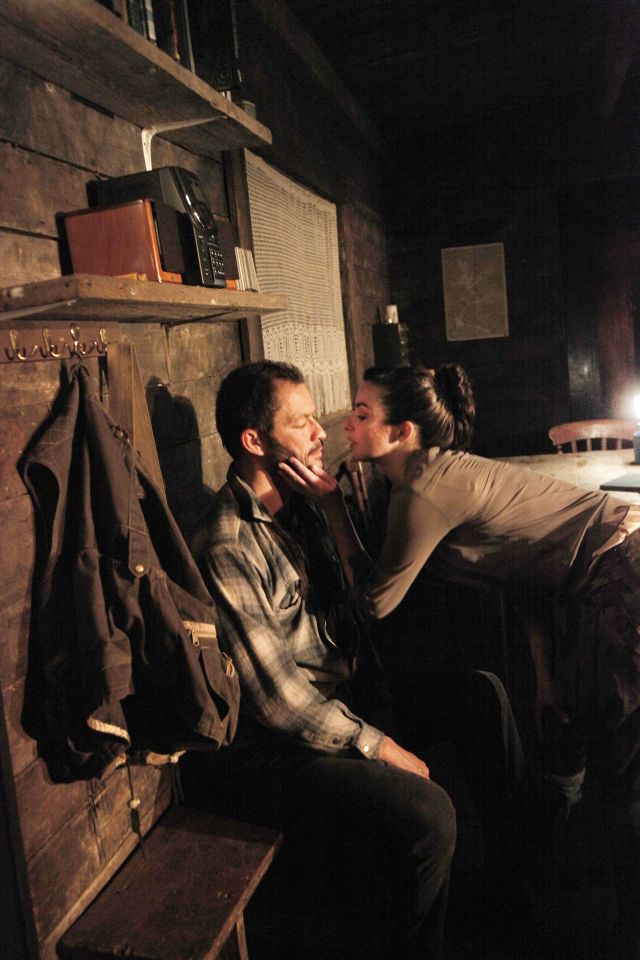

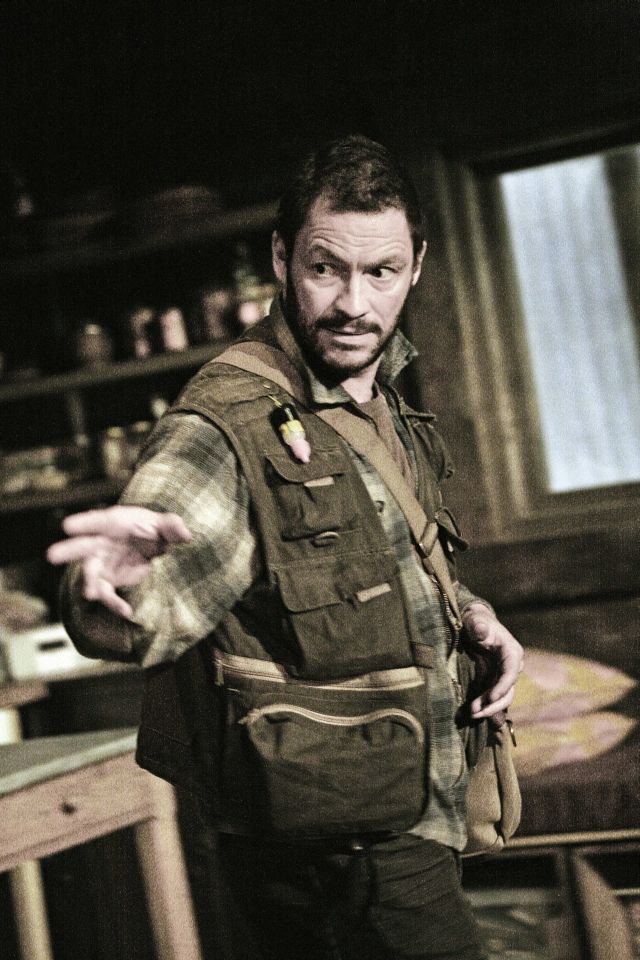

At first, the wooden cabin before us seems the perfect bolt-hole in which to repair with a loved one, listening to music, reciting poetry, and heading down to the river - the nearest railway station a blessedly remote four miles away. But is what we're watching any more "real" (for which, read accurate or trustworthy) than our initial sense of a bearded Dominic West (pictured above with Laura Donnelly) playing an unnamed man who, on the surface anyway, would seem to be a poster boy for sensitivity, aesthetic awareness, and cooking skills, to boot? Look for sales of fresh fish to soar in SW1 during the run of a play that celebrates the culinary art to an extent not seen since Clare Higgins served up roast lamb some years back in Vincent In Brixton.

And yet, the idyll is scarcely as bucolic as one might assume. The moonless night exalted early on suggests a gothic eeriness that intensifies when the man's new girlfriend (Miranda Raison, pictured below with West) is believed missing, necessitating a panicky call to the police. Only then does the cabin door open and we are greeted by a second woman (Donnelly, in a glistening performance) who may just possibly be the latest in an ongoing series to this cliff-top retreat of multiple female visitors over time. The play pulsates with sexual possibility and declarations of love that get revised, its apparent movement towards solitude and self-reproach negated by a spine-tingling twist not to be revealed here. Let's just say that the cycle of deceit hurtles ever onward, much like the rushing water heard in between scenes in Ian Dickinson's sinuous sound design.

And yet, the idyll is scarcely as bucolic as one might assume. The moonless night exalted early on suggests a gothic eeriness that intensifies when the man's new girlfriend (Miranda Raison, pictured below with West) is believed missing, necessitating a panicky call to the police. Only then does the cabin door open and we are greeted by a second woman (Donnelly, in a glistening performance) who may just possibly be the latest in an ongoing series to this cliff-top retreat of multiple female visitors over time. The play pulsates with sexual possibility and declarations of love that get revised, its apparent movement towards solitude and self-reproach negated by a spine-tingling twist not to be revealed here. Let's just say that the cycle of deceit hurtles ever onward, much like the rushing water heard in between scenes in Ian Dickinson's sinuous sound design.

What can't be cheered enough is the precision of a chamber production from Rickson that replaces the galvanic splendour and fury of Jerusalem with a series of highly charged moments equivalent to the "million lightning bolts" wished for early on by the bluntly spoken Raison. Eyes brimming over with an equal awareness of love and loss, West cuts a figure of unforced, casual masculinity as integral to this occasion as was Mark Rylance's outsized swagger to the posturing roustabout, Johnny Byron; it's a remarkable portrayal, not least for the way it finds something desolate in deception that ups the emotional stakes.

And through the play flows writing alive to playfulness and nuance, whereby motifs of capture apply both to fly-fishing and within domestic relationships, and to a revelry in language that can speak of water as "gin-clear" and of a "chapel of cloud" without lapsing into the faux-poetics that could ensue. Nor can one ignore the gathering sense of a spectral landscape populated by ghosts and the living dead and where people cannot be erased, whether we wish them to be or not. (A recurring image is of a woman's face that has been scratched out.)

And through the play flows writing alive to playfulness and nuance, whereby motifs of capture apply both to fly-fishing and within domestic relationships, and to a revelry in language that can speak of water as "gin-clear" and of a "chapel of cloud" without lapsing into the faux-poetics that could ensue. Nor can one ignore the gathering sense of a spectral landscape populated by ghosts and the living dead and where people cannot be erased, whether we wish them to be or not. (A recurring image is of a woman's face that has been scratched out.)

To be sure, it may take a particular audience to respond to Butterworth's verbal patterns - the way, for instance, that Donnelly speaks of being "flipped over" in her love-making just as Raison cites the fish-like "flip-flopping" of her dead father. And the steady, often silent emphasis on ritual (accompanied for the most part by candlelight) will disappoint those who want more of the clamour with which Jerusalem imprinted itself upon an eager public. This is without doubt a darker play, and shorter (80 minutes), and more encoded, most importantly of all. But it's a testament to the achievement of all involved come the finish that one doesn't know whether to unlock the cryptogram yet further. Or to cry.

Add comment