theartsdesk Q&A: Composer John Kander | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Composer John Kander

theartsdesk Q&A: Composer John Kander

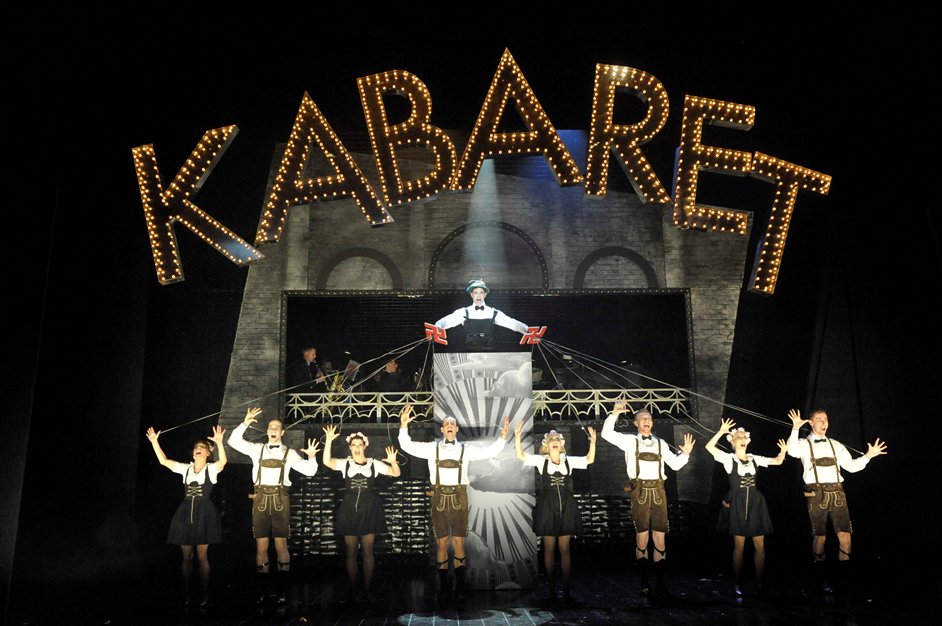

Willkommen, bienvenus, welcome: the creator of the music in Cabaret and Chicago

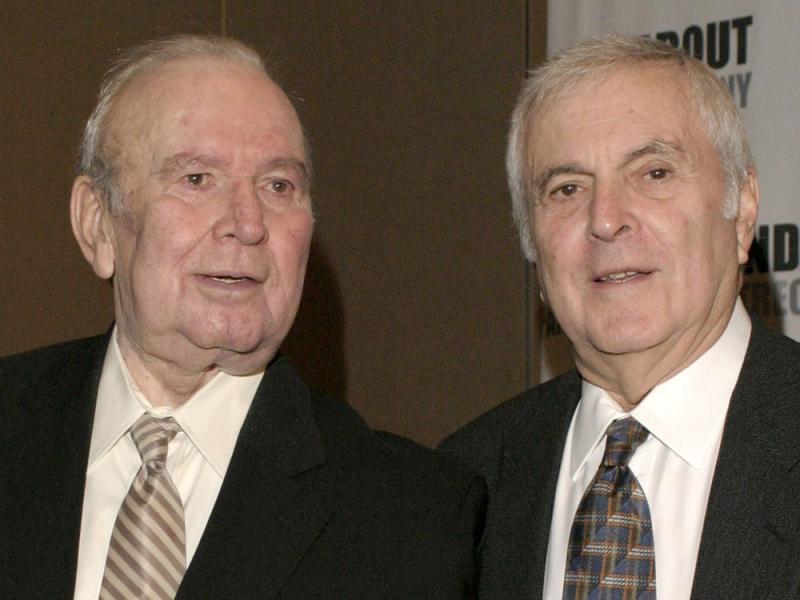

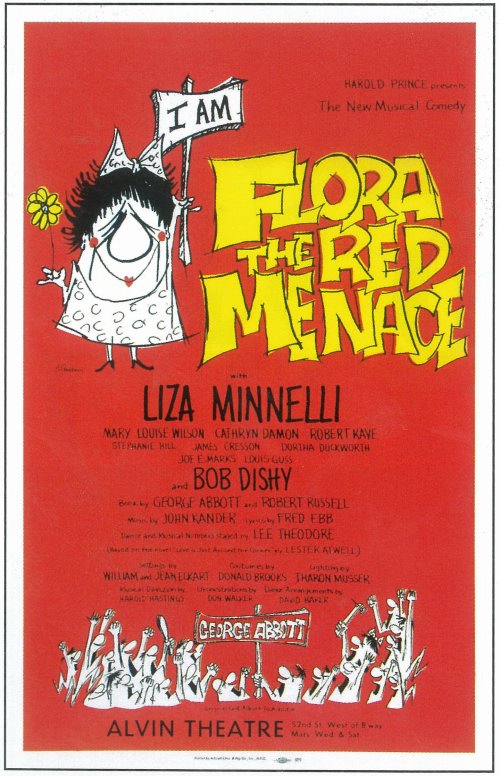

In 1972 John Kander and Fred Ebb were invited by Bob Fosse to a private screening of his film version of their hit stage musical, Cabaret. The movie starred their protégée, Liza Minnelli, who at only 19 had won her first Tony in Kander and Ebb’s first show, Flora the Red Menace, and for whom they would go on to write “New York, New York”. “Liza was our girl, and we cared very deeply about her.

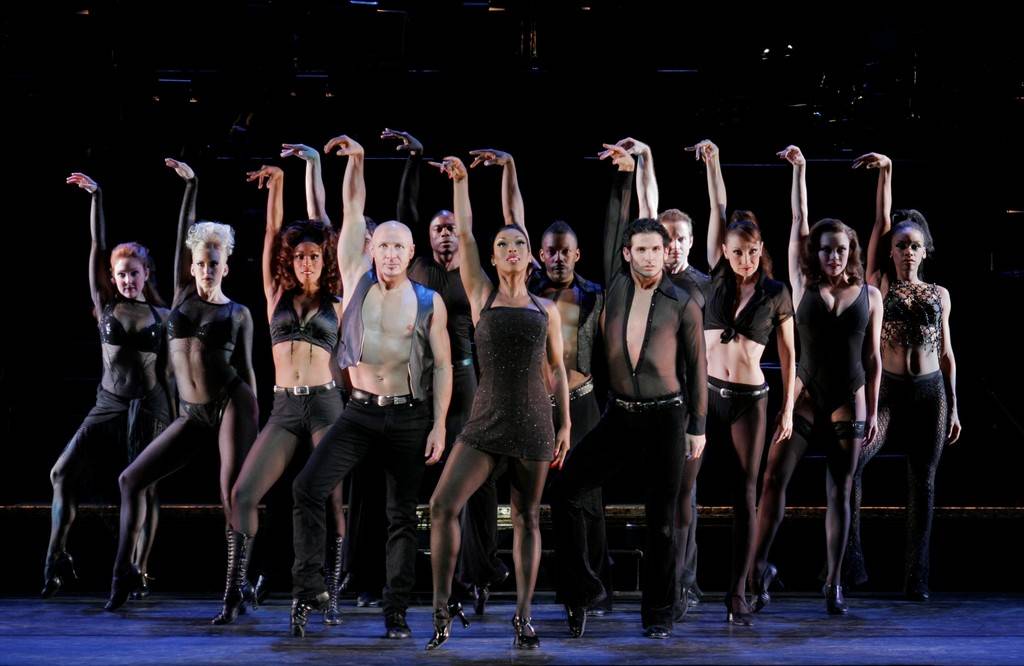

It’s not impossible to see why. When it eventually came in 2002, the movie adaptation of their other huge hit, Chicago, kept faith with its theatrical template. Fosse slung out all but two of Cabaret’s characters, half of the songs and most of the plot. But the crucial change was in the person of Sally Bowles. In Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin stories Sally is an indifferent and mostly unemployed singer. When Kander and Ebb saw the film with an audience, they changed their tune. It comes up every time the show returns to the stage - currently in Rufus Norris's revival of his own 2006 production at the Savoy Theatre starring Will Young as the Emcee and Michelle Ryan as Sally: exactly how talented should Sally Bowles be?

Born in Kansas City in 1927, Kander is just old enough to have served in the war. When he saw South Pacific in the theatre, he was familiar with the theatre of war in which it was set. A graduate of Columbia University where he studied composition, his early career consisted of a series of lucky breaks. He landed his first job in theatre as a substitute pianist on West Side Story, from which he was employed as an audition pianist on Gypsy in 1959. But the luckiest break was being introduced to Fred Ebb in 1962 by their joint publisher. For the producer/director Hal Prince they wrote Flora the Red Menace in 1965. With book writer Joe Masteroff already on board, the four of them embarked on a show set in the Berlin nightclubs of the last, louche days of Weimar Republic. Many musicals followed Cabaret (1966), including Zorba, Kiss of the Spiderwoman and Fosse, but the names of Kander and Ebb are etched into musical history above all for two record-breaking shows. While Cabaret was an instant hit, Chicago (1975) was deemed too cynical for the worldweary mid-1970s, and really only came into its own at a time of high prosperity in the 1990s.

Born in Kansas City in 1927, Kander is just old enough to have served in the war. When he saw South Pacific in the theatre, he was familiar with the theatre of war in which it was set. A graduate of Columbia University where he studied composition, his early career consisted of a series of lucky breaks. He landed his first job in theatre as a substitute pianist on West Side Story, from which he was employed as an audition pianist on Gypsy in 1959. But the luckiest break was being introduced to Fred Ebb in 1962 by their joint publisher. For the producer/director Hal Prince they wrote Flora the Red Menace in 1965. With book writer Joe Masteroff already on board, the four of them embarked on a show set in the Berlin nightclubs of the last, louche days of Weimar Republic. Many musicals followed Cabaret (1966), including Zorba, Kiss of the Spiderwoman and Fosse, but the names of Kander and Ebb are etched into musical history above all for two record-breaking shows. While Cabaret was an instant hit, Chicago (1975) was deemed too cynical for the worldweary mid-1970s, and really only came into its own at a time of high prosperity in the 1990s.

Ebb died in 2004, since when Kander has brought to fruition two collaborations. But here he talks to theartsdesk about his early years on Broadway, and the story of Cabaret.

JASPER REES: When a show doesn’t work is there a way of knowing why?

JOHN KANDER: When the disappointment happens everybody sits round bemoaning their fate and blaming this and blaming that. It’s very mysterious. There’s no way of knowing. In 1966 Cabaret was very successful in New York City. Shortly after that we came here and did the same production and a wonderful cast and Judi Dench as Sally Bowles was just out of this world. And the show got a very "neurgh" reaction. It was never successful here until the production. The same thing with Chicago. When it opened in New York it got very mixed reviews. A production in London was not really very successful. And then all these years later it reopened in New York and here, even though it was a different production still the same words, the same music, the same chorographic approach.

Why did it work the second time round?

Boy, if I knew that... I don’t have too much of a theory. I think there are things that contribute to it. One is that for a whole period we were deluged with big lavish musicals where the sets were almost more important than the content. And then something like Chicago, which was very spare, where all you have is content, is suddenly seemed new and refreshing. Some people have said that we’re more cynical today. But when Chicago happened we were just off the Watergate scandaI.

The obsession with celebrity…

The obsession with celebrity…

Is sort of out of the closet. Do you think it’s any different now though? In the Thirties Anything Goes was all about that.

The movie came soon after the hit stage show, unlike with Chicago. Has that made it hard to live as a stage show?

That’s difficult to answer. The movie of Cabaret is wildly different from the stage piece whereas the movie of Chicago is ingeniously theatrical and yet it’s film.

Liza Minnelli made it her own.

There is a big difference. In the show Cabaret Sally is not nearly as much of a focus as she is in the film. In the play I Am a Camera Sally Bowles is the focus of everything. In the theatre piece of Cabaret she is just one of several important characters.

Why did you bring her down in size?

I didn’t make that decision. We started off doing the Berlin stories of Isherwood and we were not doing I Am a Camera. We went back to the original stories. We were doing a piece about Berlin and about that time. It was not specifically about Sally Bowles.

On the stage she’s British and in the movie she’s American. But she’s the same girl really

How did the part get enlarged for the movie?

Oddly enough it was not something that Fred and I were particularly consulted about. Actually that’s the only answer I can give. We didn’t participate very much.

Did you mind?

No but partly because Liza was our girl and we cared very deeply about her. But when they finally showed it to us – this is a terrible thing to confess – they had a screening just for Fred and me and we sat there afterwards and didn’t know what to say to these people whom we liked so much because we just hated it.

So what did you say?

I think we stammered a lot and tried to make it through. But then we saw it in the theatre and thought it was a masterpiece and what we had to do was get rid of our own show first. The Lotte Lenya character was gone, the Jack Gilford character was gone. It was just a completely different thing. Then after we’d had that experience and erased it from our heads and saw it for what it was I thought it was just brilliant.

Is she a different girl in the film and the show?

Essentially no. On the stage she’s British and in the movie she’s American. But she’s the same girl really. She’s probably tougher on the stage. Liza’s vulnerability is just everywhere. The Sally Bowles that she created and the milieu in which she created it are simply not the same as it is on the stage. She’s never played it on the stage.

How well should Sally be able to sing?

That’s tricky because if she sings as well as Liza you can’t figure out why she isn’t working all the time. It’s difficult to have an audience involved with a character who is supposed to be a second-rate talent. If a second-rate talent is portrayed by a second-rate talent it simply doesn’t work. I’ve seen that tried too. So the solution to that is to not deal so much with the fact of Sally’s talent or lack of but really more with her own self-destructiveness.

Jane Horrocks (pictured right), who played the role in Sam Mendes' production at the Donmar in the 1990s, says you told her to sing it as a rant.

Jane Horrocks (pictured right), who played the role in Sam Mendes' production at the Donmar in the 1990s, says you told her to sing it as a rant.

I told her to make it a train wreck. She was terrific in it. I remember when we working on it and I was trying to figure out some way to make that girl with that voice land the piece.

Would you like to be involved every time?

Oh no I’m so far distanced from both of those pieces. You work on something whether it’s a show or a song or a novel and that’s all you’re doing, that’s where your focus is, and then it gets done. Hopefully it gets done, if it’s a theatre piece, in a way that you like. And then it’s over. Really it’s over. It’s not that you don’t relate to it and have affection for it but that’s not what you’re doing any more. (Pictured overleaf, Michelle Ryan as Sally Bowles)

But a lot of people stay wedded to their shows?

You stay wedded to the piece until you get to the point where you can say, “Ok, that’s what I meant. It’s done and it’s out there.” Then sometimes you go back and see it with somebody else’s take on it and find that it’s fascinating but find that almost it’s as if it was by somebody else. When you have a piece that’s never quite worked. If you write a song you are very involved when you’re writing that song and then somebody sings it just the way you want it and maybe in just the right setting. From then on you still love the song but it’s not your concern any more.

How did you get involved in West Side Story?

How did you get involved in West Side Story?

In West Side I was just a substitute pit pianist.

Did it give you a taste for what was possible?

Oh sure. What happened with West Side Story… this is the story of how your life is made up of really accidents. Almost anything that you could think of that’s happened to you if you think about it hard enough is just because of an accident. I was in Philadelphia meeting with an orchestra because of a show that I was conducting in New York. I went to the opening night of West Side Story while I was there and it was overwhelming and for some reason I was at the party afterwards at a hotel. There was a big bar in the centre and there were about 60 people trying to get a drink and it was not being very successful. I’m not the world’s most aggressive fellow. A little man standing in front of me saw my distress and said, "Just tell me what you want and when I order mine I’ll order yours." He did and we talked for a little bit. It was the pit pianist with West Side.

I played piano in a Russian whorehouse in Shanghai for three days. That’s another long story

We struck up a mild kind of acquaintance and then when he took his vacation he gave me a call and said, "Would you be interested in subbing for me while I’m gone?" I said, "Sure." So I did. During the weeks that I was playing in the pit they were also putting new people into the show so I was playing those rehearsals. And then the stage manager got used to seeing me around. The next thing that was happening was a show called Gypsy. She was the stage manager for that and needed somebody to sit there all day and play while people auditioned for Robbins. That went on for weeks and weeks and weeks.

Did you know that was an opportunity?

I just said "Sure" a lot. It sounds untruthful but it’s true: I’ve never had very much ambition and I’ve certainly never had the courage to ask people for favours to get places.

How did they know you could compose?

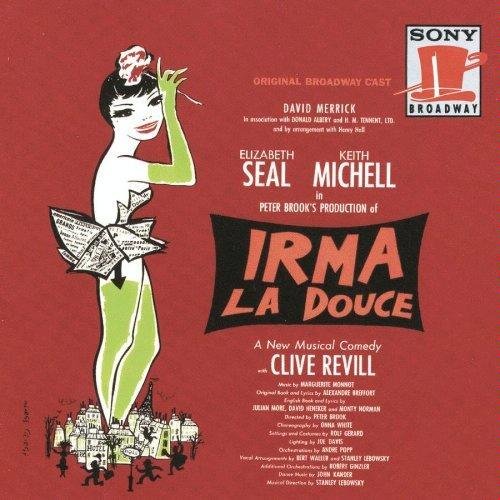

I was a pianist, I was a vocal coach, I had always written. I was a composer but they didn’t know that. But I was lucky, I could work. And the nice thing about the theatre is it’s very small and if you once go through that door that marks you as a dependable professional person people remember and offer you jobs. So I was playing the auditions. Did I think that would lead to something? Absolutely not. What it led to was the Jerry Robbins got so used to me he asked me to do the dance music for Gypsy. Literally the conversation was "Do you want to do this show with me?" and I said, "Do you want me to?" And he said "yeah" and I said "yeah". Gypsy was the experience where I was around a lot like a fly on the wall. Because of that when Peter Brook did Irma La Douce in New York I was then asked to do the dance music for that. And by that time you are so well acquainted in this tiny little community that if you write something you can get it to just about anybody. And so I did. I had a show called Family Affair which I wrote with James and William Goldman. It was a flop but a respectable flop. The fact that it got on was the amazing thing. What I guess I’m trying to say is if I had been able to order my own drink at the bar in Philadelphia after West Side Story I’m not sure I ever would have had a career.

I was a pianist, I was a vocal coach, I had always written. I was a composer but they didn’t know that. But I was lucky, I could work. And the nice thing about the theatre is it’s very small and if you once go through that door that marks you as a dependable professional person people remember and offer you jobs. So I was playing the auditions. Did I think that would lead to something? Absolutely not. What it led to was the Jerry Robbins got so used to me he asked me to do the dance music for Gypsy. Literally the conversation was "Do you want to do this show with me?" and I said, "Do you want me to?" And he said "yeah" and I said "yeah". Gypsy was the experience where I was around a lot like a fly on the wall. Because of that when Peter Brook did Irma La Douce in New York I was then asked to do the dance music for that. And by that time you are so well acquainted in this tiny little community that if you write something you can get it to just about anybody. And so I did. I had a show called Family Affair which I wrote with James and William Goldman. It was a flop but a respectable flop. The fact that it got on was the amazing thing. What I guess I’m trying to say is if I had been able to order my own drink at the bar in Philadelphia after West Side Story I’m not sure I ever would have had a career.

What were you doing?

Conducting and arranging and playing auditions. I was always able to earn a living.

Did music figure in your life during the war?

Music’s been in my life since I was six years old. I guess a little bit. I played piano in a Russian whorehouse in Shanghai for three days. That’s another long story. It was the warmest place in Shanghai because there were no radiators in Shanghai and everybody aboard my ship was there. I think a lot of people got laid because I was playing the piano.

I hope you were rewarded.

We won’t go into that. Music was never far from me. It’s terrible to say that you had a terrific family but I did. It doesn’t leave much room for exploration of what caused this and what caused that. Music was something that was very much a part of our lives. My father had a big booming baritone voice. He loved to sing and everybody loved to hear him. My grandmother played the piano, my aunt played the piano, my mother was tone deaf. But she had rhythm.

Did you train musically?

Did you train musically?

Oh sure. I started playing piano when I was about four. I had the piano. I had an aunt who helped me find out how you could actually make a chord, which I can remember to this day. It was a good old C major chord. That your own fingers could make that sound was a thrill. When I was six they let me have piano lessons with a lady who lived four blocks from us who if I had a good lesson gave me goats milk and cookies and played some Wagner. Music was always such a pleasure for me. My brother loved to sing. We would often sit around in the living room after diner and as I got to be pretty good people would sing.

When did you realise you wanted it to be your profession?

I think I always did. I don’t think I ever had a real question about it and I didn’t have parents who said, no no you mustn’t do that. I do remember …I must have been about 13, I was at summer camp which my brother and I both went to and which I loved. They always had a councillor there who put together shows and when I was 13 they had a guy there who just couldn’t do it. And somehow or other, because I was really a pretty good pianist, I put together the show the kids did and at the end of the summer the camp director gave me 50 bucks. I thought, holy shit, I could make money doing this. I think that was the first time I ever thought you could get paid for doing something that you loved. Music was just what I did. Music and theatre.

Were you steeped in theatre too?

My brother and I both had enormous enthusiasm for theatre. On spring vacations we would come to New York with our folks and go to the theatre every night. I saw Lady in the Dark with Gertrude Lawrence, I saw Ethel Merman in Something for the Boys. I do remember that when we came to New York to see Carousel my brother and I and my folks were headed to the theatre and they met some friends on the way to the theatre that they started talking to. Eddie my brother and I were getting more and more anxious. We finally grabbed our tickets from them and ran to the theatre. The short answer to your question is there was a terrific enthusiasm for theatre. My brother and I, if he was on one side of my folks and I was on the other, as the house lights went down and the lights went up on the curtain we would instinctively move forward.

How did you meet Fred Ebb?

How did you meet Fred Ebb?

Fred and I were signed to the same publisher. He had had some pieces done and I had had this musical done, A Family Affair, which was not successful but which happened which made me very very happy. My publisher literally said, "I think you two guys should meet each other, I think you’d like each other." It was an arranged marriage. And it took, almost instantly.

Why?

I cannot tell you, because we were so different. But I think our differences sort of meshed. Fred was very much a New Yorker. We had different sort of ambitions. My ambition was to have a good time or to feel good. Fred had a considerable drive to make things happen and for recognition. It’s too hard to give a short answer except that he was very much city. He came to my house in the country in upstate New York once complaining that I’d never invited him and in five hours he was gone.

How long did it take you to get your first show on?

We wrote a show called Golden Gate which almost got on but never did. It came so close that we were auditioning for people. Hal Prince who was actually more a producer than a director, whom I had known – that’s another story … George Abbott the director – Hal was his producer – and there was a musical he was putting together for Mr Abbott to direct and he asked Mr Abbott to listen to us. And so we played our score for Golden Gate. Mr Abbott’s enthusiasm was strong enough so that he hired us to do a musical called Flora the Red Menace. Enter Miss Minnelli. That’s where we met Liza. How we met Liza – there’s a long story before that as well. She was 18. Flora was a really interesting experience and an educational one but Liza got a Tony Award out of it. Liza became Fred’s mentor really. And just about everything she did he and/or we had a hand in. And that went on for a long time. But Fred was I certainly think the most important man in her life. Liza once said, "Sometimes I think I’m an invention of Fred." And in some ways it’s true. If anybody has ever see Fred Ebb sing "Liza with a Z" you can see every little finger of Liza come out.

We wrote a show called Golden Gate which almost got on but never did. It came so close that we were auditioning for people. Hal Prince who was actually more a producer than a director, whom I had known – that’s another story … George Abbott the director – Hal was his producer – and there was a musical he was putting together for Mr Abbott to direct and he asked Mr Abbott to listen to us. And so we played our score for Golden Gate. Mr Abbott’s enthusiasm was strong enough so that he hired us to do a musical called Flora the Red Menace. Enter Miss Minnelli. That’s where we met Liza. How we met Liza – there’s a long story before that as well. She was 18. Flora was a really interesting experience and an educational one but Liza got a Tony Award out of it. Liza became Fred’s mentor really. And just about everything she did he and/or we had a hand in. And that went on for a long time. But Fred was I certainly think the most important man in her life. Liza once said, "Sometimes I think I’m an invention of Fred." And in some ways it’s true. If anybody has ever see Fred Ebb sing "Liza with a Z" you can see every little finger of Liza come out.

One of the things that happened when we did Flora the Red Menace Hal Prince did something that no producer in his right mind today would do. He said about two weeks before it opened, "Whatever happens with Flora the Red Menace the day after it opens we’ll meet at my house and talk about the next piece." Now that’s a real vote of confidence and that’s exactly what happened. Flora was just moderately successful but we met the next day at Hal’s house and began work on a piece which eventually became called Cabaret.

If you sit on a stack of books of German music somehow or other it’s all going to come into your body without your thinking about it

Whose idea was Berlin?

I’ve always assumed it was Hal. Joe Masteroff was already on board. Which came first, Hal or Joe, I’m really not sure. Then we started meeting regularly. This was what made it work. We met and we talked and we talked and we talked and we talked and we talked. What if somebody throws a rock through the window? What if Sally has an abortion? So that after all the weeks of talking – and this is the secret to a collaboration – we were all doing the same piece. And Fred and I were writing. We must have written, God, 60 songs. A lot of them were what we called Berlin songs. This was before the Master of Ceremonies (pictured below, Will Young as the Emcee) was clear in our heads. There were to be Berlinesque songs in between scenes and then it developed that we would have one character do them all. I began to listen to a lot of German vaudeville songs, German jazz of the Twenties, and Fred was getting very involved in German expressionist painting. The fact is we wrote a lot.

It’s more than just a pastiche though.

Oh sure. From a musical point of view what I did after listening to all of this stuff was to just throw it away and begin to write. If you sit on a stack of books of German music somehow or other it’s all going to come into your body without your thinking about it.

Which did you write first?

Which did you write first?

The very first song was “Willkommen”. That was the thing that Fred and I tended to do anyhow. The first song in a show tends to tell you a lot about what’s going to happen musically. Sondheim said something like that in an interview. It’s hard to explain unless you’re a composer but even certain musical intervals occur to you. The score of Cabaret is about a minor second. C to B natural underneath. It sounds really dumb to say that but of course it’s not. It’s there all the way through the show. "Willkommen". Even in the movie in the money song. I can’t tell you why. It just comes out of your fingers. There was a show that I looked back on it years later and realised the show was mainly about a minor sixth. The point is if you write the first piece first without being conscious of it it sort of dictates something that’s going to happen musically in the show.

Which was the song that made you think you’d finished the show?

I guess the last song really was “Cabaret”. There was some resistance to calling it Cabaret, I think from Hal. I can see the four of us standing around talking about this, whether it was a good idea or not. But “Cabaret” was the last major song for the show. It was quite satisfying because we thought the song has legs but we were writing a song that had a relentlessly cheerful sound to it to be sung by a woman who was deciding to have an abortion. I think that’s something that all the way through our careers that Fred and I loved doing. If you could say something that seems to be saying one thing and is actually saying something else.

At the end of the second act you really step on the audience’s neck

How about “Tomorrow Belongs to Me”?

“Tomorrow Belongs to Me” was originally one of the Berlin songs. We had lots of those songs. We wrote our way into those songs. That’s the perfect example of a song like Cabaret. Originally it was a three-act musical. At the end of the first act the waiter sang “Tomorrow Belongs to Me” in a really angelic way so that everybody would walk out in the intermission thinking aren’t those really nice guys and wouldn’t you like to be a member of that fraternity, so that at the end of the second act you really step on the audience’s neck. The very conscious point was to make people realise that it’s not about them, it’s not about the Germans, it’s about us. We would have been a part of that. When we started rehearsal there was a housing development in Chicago. This was 1966. Suddenly because of the laws you could not segregate any more and there was a black couple that came into this housing development. There was a picture of a mob on either side of this path while this couple was walking into this housing development. It’s from Life magazine. It was a double spread. The hatred on their faces for this black couple was so visceral. Hal put that up on the bulletin board and said, "That’s what our show’s about." It’s what you can do if you’re part of a mob that hates anything: the power that you have.

Liza Minnelli performs 'Mein Herr' from Cabaret

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

The Producers, Garrick Theatre review - Ve haf vays of making you laugh

You probably know what's coming, but it's such great fun!

The Producers, Garrick Theatre review - Ve haf vays of making you laugh

You probably know what's coming, but it's such great fun!

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

Comments

I would love to read his