theartsdesk in Røros, Norway: Fiddling amongst the slag heaps | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Røros, Norway: Fiddling amongst the slag heaps

theartsdesk in Røros, Norway: Fiddling amongst the slag heaps

At Landskappleiken, folk music's faithful gather along the trunk line to Trondheim

It’s just before midnight on Friday. A few hundred couples circle the floor of a school gym. On stage, violinists play a rhythmic music which cycles repetitively. Coloured with sad, minor notes, it sounds like a stately ancestor to bluegrass. Hands joined, the couples raise their arms above their heads. The woman spins. Breaking the link, the man suddenly bobs downwards, hops up and spreads his arms apart in a come-hither gesture. His partner’s raised hands say no.

But he doesn't give up. He’ll try again and again to entice her. This is the Røros Pols, a dance unique to a region a third of the way up Norway, on the inland plateau shelving up to the border with Sweden. Getting to Røros involves taking a train north-east from Oslo, and then changing to the trunk line from Hamar to Trondheim.

The dance is the post-script to the day at Landskappleiken, Norway’s annual traditional music and dance competition. Landskappleiken (“national competition”) is hosted by a different town each year. For 2013, it has descended on the stunningly beautiful Røros (pronounced “rare-ross”) and is being held in the town’s somewhat less lovely school and sports arena. Just under 4000 people live in Røros. The event has drawn 7000, 1000 of whom are players and performers. People sleep on classroom floors, in cars and camper vans. There’s a camp site too. Many wear traditional costume (pictured right, third-placed singer Unni Boksasp at Landskappleiken 2013). Saying the four days are important in the diary is an understatement: Landskappleiken is fundamental to Norway’s identity.

The dance is the post-script to the day at Landskappleiken, Norway’s annual traditional music and dance competition. Landskappleiken (“national competition”) is hosted by a different town each year. For 2013, it has descended on the stunningly beautiful Røros (pronounced “rare-ross”) and is being held in the town’s somewhat less lovely school and sports arena. Just under 4000 people live in Røros. The event has drawn 7000, 1000 of whom are players and performers. People sleep on classroom floors, in cars and camper vans. There’s a camp site too. Many wear traditional costume (pictured right, third-placed singer Unni Boksasp at Landskappleiken 2013). Saying the four days are important in the diary is an understatement: Landskappleiken is fundamental to Norway’s identity.

Landskappleiken bears some resemblance to the Cardiff Singer of the World competition. Singers – and, in this case, violinists and dancers too – perform before juries and are judged. But Landskappleiken was first held in 1896 rather than 1983. Originally, it was just for solo violin, but solo, unaccompanied vocal (kveding), dance and violin groups have since been incorporated. The competition divides each strand into four classes, depending on age, skill and how long the entrant has been performing. Class A is the top, then B, C and D. This means there are 24 finals, some stringing together entrants from different classes. It’s possible to watch two hours of fiddle playing, break for an hour and then take in a further four hours. Handily, local brewery Atna has created a special Landskappleiken beer to help wash it all down.

In Norway, violin doesn’t only mean the familiar four-stringed instrument. The country is home to the Hardanger Fiddle (the Hardingfele), a stunningly loud instrument which has a second set of resonating sympathetic strings making a drone (pictured left, Lars-Ongar Meyer Fjeld with a Hardanger Fiddle made in 1917). There are finals for both violin (Fele) and Hardanger Fiddle. Dance is spilt into dans – where couples perform the traditional dances that the Røros Pols drew from – and the extraordinary Laus.

In Norway, violin doesn’t only mean the familiar four-stringed instrument. The country is home to the Hardanger Fiddle (the Hardingfele), a stunningly loud instrument which has a second set of resonating sympathetic strings making a drone (pictured left, Lars-Ongar Meyer Fjeld with a Hardanger Fiddle made in 1917). There are finals for both violin (Fele) and Hardanger Fiddle. Dance is spilt into dans – where couples perform the traditional dances that the Røros Pols drew from – and the extraordinary Laus.

For the Laus, a woman mounts a chair and extends a stick above her head. A hat dangles from one end. Circling the stage, a male dancer bobs, tumbles, executes push-ups – anything, seemingly, to exhibit his manhood. The goal is to kick the hat from the stick. He gestures for it to be raised higher and higher. He teases, feigning a jump. Then, he leaps – flipping over in the air to kick it off. Mostly, it works and the audience goes mad. Some dancers are subtle and elegant, but cheers greet the more exaggerated gestures. (Watch footage of the amazing, gravity defying Hallgrim Hansegård’s winning Laus at Landskappleiken 2013 on the final page.)

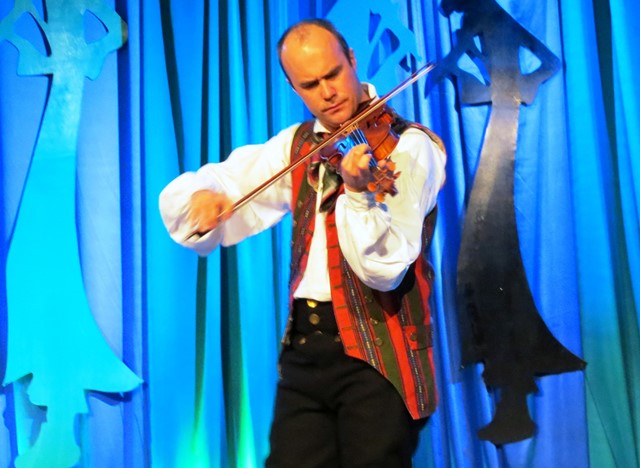

It is a tough audience though. Older spectators tut the fiddlers who go off on unexpected paths. A trill here, a flourish there? Not welcome. Tsk-tsk they go. Unexpectedly, hours of fiddle – Hardanger and standard – isn’t a trial (pictured right, first-placed fiddle player Andreas Bjørkås at Landskappleiken 2013). It’s absorbing and, with the Hardanger Fiddle, like a form of serial music. As the pull of the Hardanger becomes irresistible, it’s clear why the Lutheran church took against the instrument and its implicit invitation to dance.

It is a tough audience though. Older spectators tut the fiddlers who go off on unexpected paths. A trill here, a flourish there? Not welcome. Tsk-tsk they go. Unexpectedly, hours of fiddle – Hardanger and standard – isn’t a trial (pictured right, first-placed fiddle player Andreas Bjørkås at Landskappleiken 2013). It’s absorbing and, with the Hardanger Fiddle, like a form of serial music. As the pull of the Hardanger becomes irresistible, it’s clear why the Lutheran church took against the instrument and its implicit invitation to dance.

More explicit messages come with the singing. A song tells of a young woman’s desire for more than one man and how she won’t choose. She wants them all. Another is about a wedding night where the groom is so drunk the bride dances with his friend. She makes off with him rather than her new husband. Less colourfully, the simple message that the cows are coming down from the mountain is put into song.

Courting and country life; sex and alcohol; difficult choices and showing off – the themes driving Landskappleiken are universal. Fitting, considering that Røros turns out not to have been the backwater it now seems to be.

Røros isn’t the most obvious destination for a visitor to Norway. It’s a five-hour train journey from Oslo, the last four zipping along a single track cut through dense woodland. Occasionally, this breaks to reveal a river or lake. Stops on the ever-ascending journey are made at small towns which quickly vanish once the trees take over again.

Arrival in Røros is different. The trees give way early. There instantly appears to be more about this place than a few houses. Along from the station, there’s a hotel. A church tower is visible from almost all points. It was meant to be seen. And churches which are meant to be seen are evidence of wealth – if not current, then an economy which thrived in the past.

Evidence for that past dominates Slaggveien, Røros’s most striking street (pictured right, Slaggveien). The name means the slag way. It leads up to massive slag heaps which loom over the town as inescapably as the church. Slaggveien’s 17th-century wooden huts are still lived in and cars with Swedish number plates are parked outside a couple.

Evidence for that past dominates Slaggveien, Røros’s most striking street (pictured right, Slaggveien). The name means the slag way. It leads up to massive slag heaps which loom over the town as inescapably as the church. Slaggveien’s 17th-century wooden huts are still lived in and cars with Swedish number plates are parked outside a couple.

Before Slaggveien’s houses became desirable addresses, it was copper that attracted people here. It built Røros, which was also known as Bergstaden: the mining town. Copper was first exploited in 1644 and the town came into being two years later. The current church was completed in 1784 and is Norway’s fifth largest, with seating for 1600 people. Despite the rapid growth and money flowing into and out of Røros, not all the returns were seen by locals. Norway was then controlled by Denmark. King Christian VII of Denmark’s insignia is placed high inside the church and many of Copenhagen’s historic copper roofs began their life in Røros. Only one director of the mining company was local. The first was German. Denmark lost its opportunity to build with Norwegian copper in 1814 when Norway passed to Sweden despite having declared independence and adopting its own constitution. Autonomy finally came in 1905.

Before assuming control of Norway, Sweden had recognised the importance of Røros – the border is 35km away – and took it in 1678. After burning it to the ground and being sent packing, they retook it in 1718, forcing miners to work at gunpoint in a second, short-lived foray. Sweden paid the price when 3000 of its soldiers froze to death – at an elevation of 640m, temperatures at Røros can drop to minus 45 centigrade. Despite the upsets, Røros thrived and mining continued until 1977 when the company went bankrupt.

Uniquely for a town where most buildings are constructed from wood, 17th- and 18th-century Røros survives intact. It was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980, with the designation later extended to include to surrounding landscape.

As striking as Slaggveien is the interior of the church (pictured left). The white-painted stone exterior is no preparation for what’s inside. Its fittings are painted bright blue, with streaks mimicking marble. With the white walls, the effect is like being inside a blueberry and cream cake. Paintings of notable locals hang, despite Christian VII’s emblem hovering over congregants. One depicts local author Johan Falkberget, who set a series of novels in the mining community.

As striking as Slaggveien is the interior of the church (pictured left). The white-painted stone exterior is no preparation for what’s inside. Its fittings are painted bright blue, with streaks mimicking marble. With the white walls, the effect is like being inside a blueberry and cream cake. Paintings of notable locals hang, despite Christian VII’s emblem hovering over congregants. One depicts local author Johan Falkberget, who set a series of novels in the mining community.

The uniqueness of Røros inspired more than Falkberget. Slaggveien became the setting for a filmed version of Pippi Longstocking and director Joseph Losey’s adaptation of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, with Jane Fonda. In this evocative place, it’s no wonder that a performance held in the church is a charged experience.

Billed as a concert “in Peder Hiorts’s cathedral”, the evening paid tribute to the mining company’s director when the church was built – Hiorts was its only Røros-born director and had first studied theology.

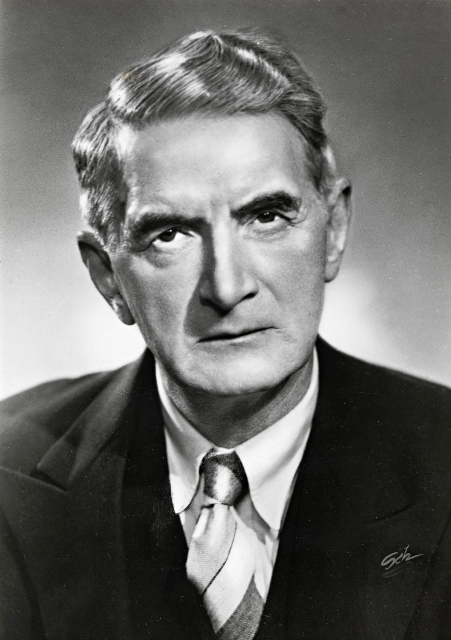

The Røros-born, 81-year-old violinist, composer and academic Sven Nyhus steered the evening through a reading from Falkberget (pictured right) and performances of Grieg who, like the 19th-century violinist Ole Bull, celebrated and propagated traditional Norwegian music. From 1971, Nyhus spent 10 years transcribing Norway’s traditional music. A century earlier, recognising its own music had been central to Norway becoming independent.

The Røros-born, 81-year-old violinist, composer and academic Sven Nyhus steered the evening through a reading from Falkberget (pictured right) and performances of Grieg who, like the 19th-century violinist Ole Bull, celebrated and propagated traditional Norwegian music. From 1971, Nyhus spent 10 years transcribing Norway’s traditional music. A century earlier, recognising its own music had been central to Norway becoming independent.

Intriguingly, the concert also featured a duet between the violin and the Swedish nyckleharp. Despite Sweden's past transgressions in Røros, its proximity means its cultural influence is integral to the region. The most breath-taking moments came with Gor Kjelleberg Solli singing from a balcony high above the alter. The evening climaxed with the Norwegian version of the Martin Luther hymn “A Mighty Fortress is Our God”.

As a window into what helps make up the fabric of Norway, Landskappleiken could have been a bone-dry marathon of dyed-in-the-wool traditionalism with all the fun extracted. But as the annual gathering of enthusiasts, performers and players it was a blast. Off the stage, few boundaries are respected. In the main gym/beer hall, spontaneous playing and singing was constant. Instruments were compared, new tricks shown off, spilling into cafés and streets. Sharing and celebrating is universal. Differences in language, styles of music or dances are – as they are anywhere – local veneers coating the familiar.

Discovering Røros isn’t new either. In the 18th century, the town had an impact on the British mineralogist and traveller Edward Daniel Clarke (pictured left), who diligently wrote up his experiences in the multi-volume Travels in Various Countries of Europe, Asia and Africa. On arriving in Røros in September 1799, he first noted surprise that a town of this scale and grandeur existed in such a remote spot. Then, he found locals had their way of doing things.

Discovering Røros isn’t new either. In the 18th century, the town had an impact on the British mineralogist and traveller Edward Daniel Clarke (pictured left), who diligently wrote up his experiences in the multi-volume Travels in Various Countries of Europe, Asia and Africa. On arriving in Røros in September 1799, he first noted surprise that a town of this scale and grandeur existed in such a remote spot. Then, he found locals had their way of doing things.

Clarke’s visit coincided with mineworkers receiving their monthly pay. Naturally, a dance marked the occasion. Taking it in – and joining in with the Røros Pols after being provided with a partner – Clarke said “when we reached the room, in which the miners and their lasses were assembled the male dancer practises every possible grimace, look and attitude that may express lasciviousness…exhibiting his amorous propensities.” He held strong views on national dances, saying all were “grossly licentious.”

He had a point and, although for different reasons, his astonishment resonates. Wherever it is held, Landskappleiken would overwhelm and amaze. But in the setting of the extraordinary, other-worldly Røros, it becomes more than special. This is a Norway rarely seen by the outside world but one which doesn’t need to keep to itself.

Watch Hallgrim Hansegård’s winning Laus at Landskappleiken 2013

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Mariah Carey is still 'Here for It All' after an eight-year break

Schmaltz aplenty but also stunning musicianship from the enduring diva

Mariah Carey is still 'Here for It All' after an eight-year break

Schmaltz aplenty but also stunning musicianship from the enduring diva

Album: Solar Eyes - Live Freaky! Die Freaky!

Psychedelic indie dance music with a twinkle in its eye

Album: Solar Eyes - Live Freaky! Die Freaky!

Psychedelic indie dance music with a twinkle in its eye

Album: Night Tapes - portals//polarities

Estonian-voiced, London-based electro-popsters' debut album marks them as one to watch for

Album: Night Tapes - portals//polarities

Estonian-voiced, London-based electro-popsters' debut album marks them as one to watch for

Album: Mulatu Astatke - Mulatu Plays Mulatu

An album full of life, coinciding with a 'farewell tour'

Album: Mulatu Astatke - Mulatu Plays Mulatu

An album full of life, coinciding with a 'farewell tour'

Music Reissues Weekly: Sly and the Family Stone - The First Family: Live At Winchester Cathedral 1967

Must-have, first-ever release of the earliest document of the legendary soul outfit

Music Reissues Weekly: Sly and the Family Stone - The First Family: Live At Winchester Cathedral 1967

Must-have, first-ever release of the earliest document of the legendary soul outfit

Album: Robert Plant - Saving Grace

Mellow delight from former Zep lead

Album: Robert Plant - Saving Grace

Mellow delight from former Zep lead

Brìghde Chaimbeul, Round Chapel review - enchantment in East London

Inscrutable purveyor of experimental Celtic music summons creepiness and intensity

Brìghde Chaimbeul, Round Chapel review - enchantment in East London

Inscrutable purveyor of experimental Celtic music summons creepiness and intensity

Album: NewDad - Altar

The hard-gigging trio yearns for old Ireland – and blasts music biz exploitation

Album: NewDad - Altar

The hard-gigging trio yearns for old Ireland – and blasts music biz exploitation

First Person: Musician ALA.NI on how thoughts of empire and reparation influenced a song

She usually sings about affairs of the heart - 'TIEF' is different, explains the star

First Person: Musician ALA.NI on how thoughts of empire and reparation influenced a song

She usually sings about affairs of the heart - 'TIEF' is different, explains the star

Album: The Divine Comedy - Rainy Sunday Afternoon

Neil Hannon takes stock, and the result will certainly keep his existing crowd happy

Album: The Divine Comedy - Rainy Sunday Afternoon

Neil Hannon takes stock, and the result will certainly keep his existing crowd happy

Music Reissues Weekly: Robyn - Robyn 20th-Anniversary Edition

Landmark Swedish pop album hits shops one more time

Music Reissues Weekly: Robyn - Robyn 20th-Anniversary Edition

Landmark Swedish pop album hits shops one more time

Album: Twenty One Pilots - Breach

Ohio mainstream superstar duo wrap up their 10 year narrative

Album: Twenty One Pilots - Breach

Ohio mainstream superstar duo wrap up their 10 year narrative

Add comment