Alright on the Night: at Glyndebourne with the OAE | reviews, news & interviews

Alright on the Night: at Glyndebourne with the OAE

Alright on the Night: at Glyndebourne with the OAE

The view from the pit as Handel's 'Rinaldo' returns to leafiest East Sussex

If you only ever listened to opera from recordings, you might overlook the fact that it's as much theatre as it is music. In the opera house on the night, it's all well and good for the orchestra to play the score and the singers to sing their parts, but on top of that you have to allow for costume changes, move the scenery, adjust the lighting and make sure you get all the right people on and off stage at the appropriate moments.

It was a strange sensation, then, to spend some time in the orchestra pit at Glyndebourne this week, as Ottavio Dantone conducted the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment in the final dress rehearsal of Handel's Rinaldo. Maestro Dantone is a baroque specialist (he's music director of the Accademia Bizantina in Ravenna) and the OAE bristles with instrumental expertise, so it was a treat to be in such close proximity as they tucked into the springy rhythms and eloquent textures of Handel's score. Yet, while this was a great opportunity to appreciate in close-up the fine detail of the woodwinds and the violin and viola sections, and listen to the interplay of the archlute and the twin harpsichord accompaniment (one of them played by Dantone himself), I hadn't the faintest idea what was happening on the stage above our heads. It was like listening to one of Handel's concerti grossi, occasionally interrupted by a bit of karaoke from the neighbours.

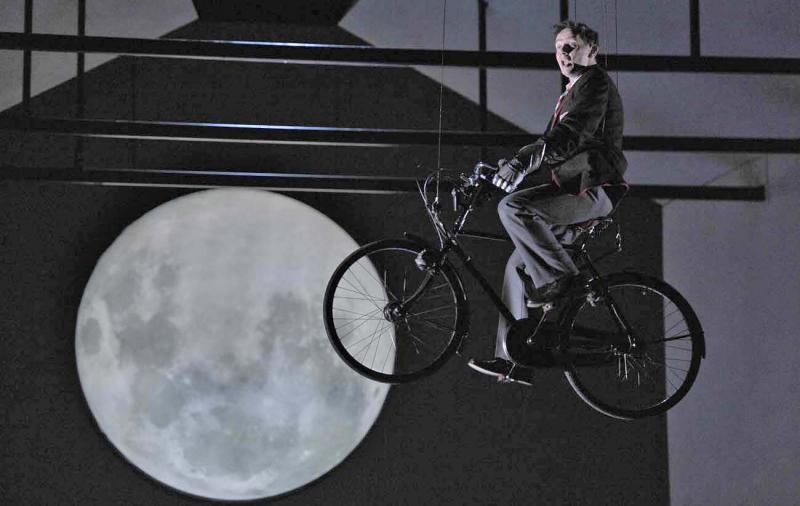

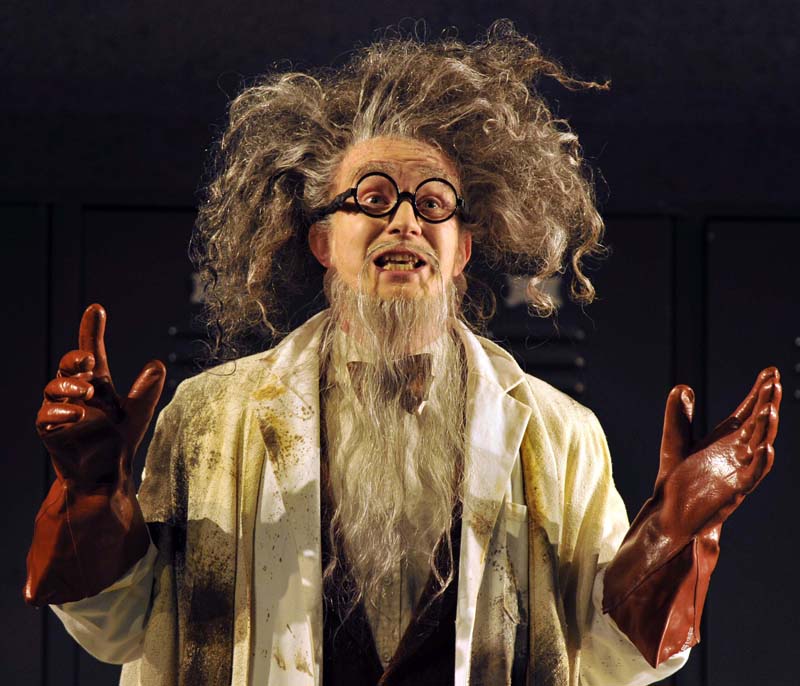

The voices sounded faint and distant, as though they were drifting in from the sheep and the picnic hampers in the Glyndebourne gardens outside. The performers existed only as sporadic bursts of clumping feet clattering across the boards overhead. From time to time the audience would burst out laughing at some jeu d'esprit in Robert Carsen's skittish production - a berserk mix of flying bicycles, mad scientists and slutty girls in miniskirts from some hallucinogenic St Trinians - but the joke was sadly lost on those of us cast into the penumbrous realm of the pit.

The voices sounded faint and distant, as though they were drifting in from the sheep and the picnic hampers in the Glyndebourne gardens outside. The performers existed only as sporadic bursts of clumping feet clattering across the boards overhead. From time to time the audience would burst out laughing at some jeu d'esprit in Robert Carsen's skittish production - a berserk mix of flying bicycles, mad scientists and slutty girls in miniskirts from some hallucinogenic St Trinians - but the joke was sadly lost on those of us cast into the penumbrous realm of the pit.

The orchestra are quite used to all this, of course, since they go through it all the time.

"When you're in the pit, because you can't see the stage, you're more aware of how the audience is behaving or if something goes wrong onstage," says viola player Annette Isserlis (pictured above with the OAE, second from left). "If you can hear that the singers are running out of breath you think 'oh gosh we'd better help them', and play a bit faster. I think because we can't see we just listen in a much more intense way, and you become aware of these things."

I'd noticed that in between the bouts of hilarity, several audience members in the front row had dozed off. "I think that may tend to happen because they have to look up very high to read the surtitles and it's tiring for their eyes," suggests Isserlis, not entirely convincingly. "But you get some appalling behaviour sometimes in the front row. It's like they forget we're here and we can see and hear everything. We've had bare feet on the rail right next to the poor cellist's nose. We've had worse actually going on under the picnic blanket... It's just unbelievable what happens."

Messrs Veuve Clicquot, Taittinger & co may have a great deal to answer for. But moving swiftly along, a small change of position within the orchestral ranks can significantly affect what a musician can see or hear.

"As it happens, this year the violas are a little further forward in the pit so I can actually read the words from the surtitles, which makes a terrific difference," says Isserlis. "Now I understand why everybody's laughing, even if it's in a rather impassioned aria. It really does change the way you play if you know what's happening onstage at the time" (Karina Gauvin as Armida, pictured above).

"As it happens, this year the violas are a little further forward in the pit so I can actually read the words from the surtitles, which makes a terrific difference," says Isserlis. "Now I understand why everybody's laughing, even if it's in a rather impassioned aria. It really does change the way you play if you know what's happening onstage at the time" (Karina Gauvin as Armida, pictured above).

It's different for the conductor, who's facing the stage, but even he must accept some compromises.

"It's always like this in every opera," shrugs Dantone, who conducted the OAE in this production of Rinaldo when it made its debut at Glyndebourne in 2011. "It depends on the height of the pit. In this opera it's not too low, it's at the medium level, but when I'm sitting at the keyboard I can't see to the back, when the singers are upstage. Sometimes I just need to use feeling. I try to hear the breath of the singer. It's the same for the orchestra, they're very good and they're used to breathing with the singers, this is important. They must not only hear and play in time but also breathe as the singers."

Pretty simple then - the musicians just have to develop a form of extra-sensory perception. Be this as it may, one thing everybody agrees on is that the Glyndebourne house is perfect for baroque opera. Countertenor Iestyn Davies is singing the title role in Rinaldo - when Glyndebourne last staged it, it was sung by the Italian contralto Sonia Prina - and he's besotted with the place (inside the Glyndebourne auditorium, pictured below).

"It's such a nice place to sing, because like many English houses it's not huge," he says. "In America the size of the houses is ridiculous - the Chicago Lyric Opera is a huge barn. But the Glyndebourne house is beautiful, the orchestra sounds big and it's always good to have lots of wood around you."

"It's such a nice place to sing, because like many English houses it's not huge," he says. "In America the size of the houses is ridiculous - the Chicago Lyric Opera is a huge barn. But the Glyndebourne house is beautiful, the orchestra sounds big and it's always good to have lots of wood around you."

The word "Glyndebourne" instantly conjures its own particular mix of images, usually involving people in evening dress popping corks. "In the early days there used to be geese waddling around," recalls Annette Isserlis. "They'd attack people's picnics that they'd incautiously left and then shit all over their picnic rugs. Green goose shit everywhere. And apparently in the very old days people used to keep their champagne cold by lowering it on a string into the lake. Then one year there was a spate of champagne thefts so people don't do that any more."

However, Davies warns that it isn't just an upmarket house-party.

"My godfather's coming to the show and he said 'perhaps you'll come for a glass of wine in the interval?' I said 'you know I'm in the opera? I'm the guy who has to sing all the stuff!' It's a mixed blessing because you have that summer camp feeling of 'we're all here in a lovely place and we're rehearsing an opera', but you also have quite a lot of people being very intense all the time, like 'I'm only here for three weeks, I've got to tell you everything I know about this piece'. It doesn't happen in a normal opera house where people are on a contract anyway and they're there to help you out. At Glyndebourne there's a lot of pressure all the time, so it can be a very stressful working environment (James Laing as the Christian Magus, pictured below left).

"But what's great about it is the facilities are amazing. They have the best rehearsal spaces in the country, right next to the stage, and there's a great office team who are behind you and they're really supportive. I'm staying in Lewes and we've had absolutely beautiful weather and it just feels like a very welcoming place. It's a mixture of the two - when you've been away from Glyndebourne you think 'I can't wait to go back', and when you're there you're thinking 'I can't wait for this show to open because the rehearsing is absolutely full-on'. You're fully immersed."

"But what's great about it is the facilities are amazing. They have the best rehearsal spaces in the country, right next to the stage, and there's a great office team who are behind you and they're really supportive. I'm staying in Lewes and we've had absolutely beautiful weather and it just feels like a very welcoming place. It's a mixture of the two - when you've been away from Glyndebourne you think 'I can't wait to go back', and when you're there you're thinking 'I can't wait for this show to open because the rehearsing is absolutely full-on'. You're fully immersed."

This combination of orchestra and conductor is, he reckons, pretty much optimum. "The OAE sounds very different depending on who's conducting it," he posits. "Ottavio Dantone brings a completely different sound to their way of playing than say Richard Egarr or Simon Rattle in particular, who's worked a lot with them. When I came to hear this show here in 2011 I don't think I'd ever heard them play better, and I think that was down to Dantone. He's a brilliant harpsichord player and director, and you really trust him. He's got an incredible sense of rhythm, which is ultimately what makes a very good musician. It's hard work, because he'll stop at anything slightly out of kilter, but he's Italian so he's full of passion and vigour. He's not a boring straight-down-the-line academic, a set-the-metronome-going kind of guy."

It's a view echoed by lutenist Elizabeth Kenny (or in this instance archlutenist, pictured below). "His conducting has inspired us a lot, particularly in my neck of the woods. I play the same figured bass as he does on the harpsichord, and he's always doing something where I think 'ooh, that's interesting', and it makes me do something different as well. It's absolutely as I imagine Handel sitting at the keyboard and it's his own music and he's kind of inventing it as it goes along, which is absolutely how this music works. You need a conductor to coordinate the stage and the pit, but he's also very communicative in every note he plays on the harpsichord, which you don't get from a conductor who doesn't play."

As for Carsen's stage production, opinions vary. Iestyn Davies thinks it's merely a contemporary interpretation of the bizarre stage directions common in Handel's time. "It's a very baroque thing to have people flying in mid air, like gods and chariots descending. We're so lucky nowadays that we have such an incredible visual culture, and it would be a weird world if we did opera very straight and dumbed it down because it was too exciting. We have to remember what we do is entertainment."

As for Carsen's stage production, opinions vary. Iestyn Davies thinks it's merely a contemporary interpretation of the bizarre stage directions common in Handel's time. "It's a very baroque thing to have people flying in mid air, like gods and chariots descending. We're so lucky nowadays that we have such an incredible visual culture, and it would be a weird world if we did opera very straight and dumbed it down because it was too exciting. We have to remember what we do is entertainment."

Kenny is slightly less effusive. "Umm... my favourite bit is Rinaldo on the flying bicycle, I love that particularly with its ET references. There's a lot of visual imagination in it. The St Trinians stuff I can take or leave really, so for those bits it's more about the music for me... she said tactfully."

Though of course being in the pit, she can't see it anyway.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Add comment