Ravel Double Bill, Glyndebourne | reviews, news & interviews

Ravel Double Bill, Glyndebourne

Ravel Double Bill, Glyndebourne

Titters for a Spanish farce, but Laurent Pelly's adventures of a naughty boy are heartbreaking

Ask opera-lovers to name their favourite one-acter and chances are the choice will be L’enfant et les sortilèges. Colette’s typically off-kilter fable of a destructive kid confronted with the objects and animals he’s damaged is set by Maurice Ravel to music of a depth which must have taken even that unshockable author by surprise. Ravel’s earlier L’heure espagnole, on the other hand, is much less likely to be top of the list.

Bringing the two closer together in this much-awaited Glyndebourne revival are not just Ravel’s equally exquisite scores, as fastidiously conducted by Robin Ticciati, and the luminous wit of director Laurent Pelly with his amazing visual sense but also, this time round, a surprising double whammy from Glyndebourne chatelaine and stage animal Danielle de Niese (pictured below with Etienne Dupuis). She’s treading the boards again first as naughty bored housewife who gets away with it then as naughty bored child who doesn’t, having just added her own, hopefully more biddable offspring to the Christie household.

There’s no room for self-indulgence here. Pelly’s movements in the Spanish bagatelle are as precise as every horological tick and character tic in the score, for all its sensuous bathing in various supernatural lights. The clockmaker’s workshop of designers Caroline Ginet and Florence Evrard gives us a wealth of Iberiana to look at, including kitsch religious art and Velazquez in lurid frames, so the singers need to be directed to the hilt to hold our attention. As they are and as they do, with a little help from Pelly’s costumes hinting at Almódovar.

There’s no room for self-indulgence here. Pelly’s movements in the Spanish bagatelle are as precise as every horological tick and character tic in the score, for all its sensuous bathing in various supernatural lights. The clockmaker’s workshop of designers Caroline Ginet and Florence Evrard gives us a wealth of Iberiana to look at, including kitsch religious art and Velazquez in lurid frames, so the singers need to be directed to the hilt to hold our attention. As they are and as they do, with a little help from Pelly’s costumes hinting at Almódovar.

For the not-so-discreet charms of the Spanish bourgeoisie, we have two bright French tenors in François Piolino as clockmaker Ramiro and Cyrille Dubois as flared aesthete Gonzalve, as well as Lionel Lhote struggling a bit with the low notes as sleazy banker Don Inigo Gómez and star stud muleteer Ramiro, and Etienne Dupuis as sensitive with some of the vocal writing as he is appropriately muscly in appearance.

What big laughs there are have mostly to do with the ease of Ramiro’s clockcase carrying and the cases’ phallic propensities (Franc-Nohain’s text is very Carry On double entendre in the first place, reference to swinging pendulums outrageously so). The rest is titter-worthy but not belly-laugh hilarious, though de Niese’s Spanish seductress, tout le monde sur le balcon as the French say, has a wonderful array of funny gestures and eloquent hand movements, and pulls out all the stops, no mere soubrette soprano in a mezzo role, in the nearest thing to a big solo, “Oh! La pitoyable aventure”. There are equal if fleeting star turns from the London Philharmonic principals, not least deliciously flaccid trombone slides (Mark Templeton, I presume) for the old man who can’t get it up.

Feline fornication is the only truly adult intrusion into the world of L’enfant, and there’s another brilliantly spinning clockface here too, but otherwise it couldn’t be more different and nor could de Niese, instantly the garçon mechant as she/he swings his/her legs restlessly on a giant chair in the opening of many breathtaking visuals. We know we’re going to love this kid, and de Niese soon brings pathos and horror to the child lost in a dream that’s mostly a nightmare.

Feline fornication is the only truly adult intrusion into the world of L’enfant, and there’s another brilliantly spinning clockface here too, but otherwise it couldn’t be more different and nor could de Niese, instantly the garçon mechant as she/he swings his/her legs restlessly on a giant chair in the opening of many breathtaking visuals. We know we’re going to love this kid, and de Niese soon brings pathos and horror to the child lost in a dream that’s mostly a nightmare.

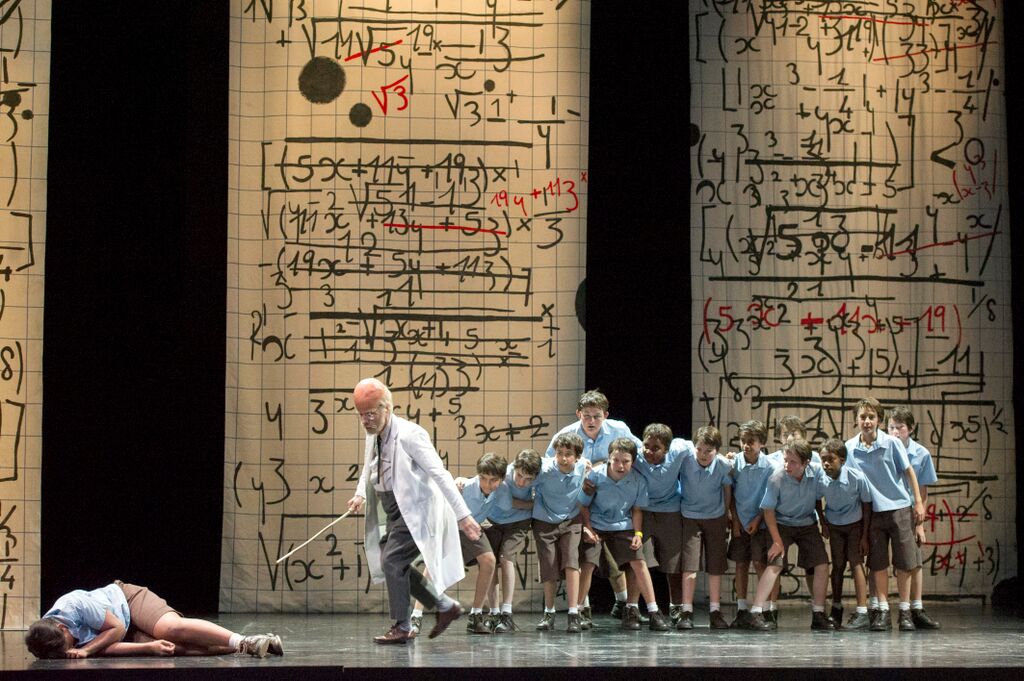

Barbara de Limburg, creator of the supermarket witch’s house in Pelly’s Glyndebourne Hänsel und Gretel, exercises restraint but also a bewitching framework for Pelly’s breathtaking costumes here as one scene glides into another. So the first half is less the usual revue, more a fluent story against the odds of Ravel’s and Colette’s demands, and Pelly does better than any director I’ve seen in not getting too much in the way of the more heartbreaking music (shepherds and shepherdesses from the torn wallpaper pictured above, princess who’s lost her storyline).There's also a great idea as the henchmen of Monsieur l'Arithmétique turn out to be multiple images of our child, spiritedly sung by local Sussex schoolboys, whose bullying adds to the terror of the maths lecture (pictured below).

Choreography – presumably by Pelly himself – for what began as a supernatural opera-ballet in the Rameau tradition is discreet but elegant, with the usual showstopping in the Foxtrot for Teapot (Piolino again) and Chinese Cup (Elodie Méchain, also a glamorously large Maman and a very big Dragonfly) and a riveting flight for the Fire (Sabine Devieilhe, perfectly stratospheric in the three most demanding roles). Nothing could eclipse the breathtaking coup of David Hockney’s blue and red tree back in the 1980s (Royal Opera, Met, Chatelet) as the music shifts to swanee-whistling, string-carpeted evocation of a garden at night, but Pelly fills his natural world with more brilliant designs, including showgirl dryads – a neat reference, perhaps, to Colette's other career – and two luminous glow worms.

Choreography – presumably by Pelly himself – for what began as a supernatural opera-ballet in the Rameau tradition is discreet but elegant, with the usual showstopping in the Foxtrot for Teapot (Piolino again) and Chinese Cup (Elodie Méchain, also a glamorously large Maman and a very big Dragonfly) and a riveting flight for the Fire (Sabine Devieilhe, perfectly stratospheric in the three most demanding roles). Nothing could eclipse the breathtaking coup of David Hockney’s blue and red tree back in the 1980s (Royal Opera, Met, Chatelet) as the music shifts to swanee-whistling, string-carpeted evocation of a garden at night, but Pelly fills his natural world with more brilliant designs, including showgirl dryads – a neat reference, perhaps, to Colette's other career – and two luminous glow worms.

How pleased Ticciati, a great proponent of meaningful silences between the music, as he told me when working on Glyndebourne Touring Opera’s Jenůfa before his big appointment as main Music Director, must have been with the infinite time it seems to take between the notes for the Child to bind the Nightingale’s wound (Squirrel in the scenario). His knack for seeming simplicity then keeps the potentially gooey wonder of the garden creatures at the naughty one’s kindness on the move, and the choral fugue that follows – an image of reconciliation after so much style-hopping – is sublime, as it must be. With Pelly’s last inspired image and de Niese making the most of her final “Maman”, the seal is set on a near-perfect evening of music theatre. Walking out into another garden on a perfect summer night seemed almost too good to be true.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Add comment