Znaider, LSO, Pappano, Barbican | reviews, news & interviews

Znaider, LSO, Pappano, Barbican

Znaider, LSO, Pappano, Barbican

Perfect depth and communication in Beethoven and Elgar

Anger and fear in Elgar, introspection in middle-period Beethoven: these are undervalued qualities in each composer’s music. Yet such moods were vividly present in two hyper-nuanced interpretations last night.

The orchestra was certainly sounding at its best, not just glossy but impassioned - not so often the case in recent years – as well as full of depths and perspectives in the multiple layers of Elgar's Second Symphony. Here was proof that if the players and their conductor work the tricky Barbican acoustics well enough, there isn't any dire need for a new London concert hall (and some of that money could go towards keeping a full-time company at English National Opera, much more important). The strings’ muscle-tone in the ensembles of Beethoven's Violin Concerto also informed the flexible ecstasy which kicks off the symphony, pouring forth ideas until it meets its flipside of melancholy from the cellos.

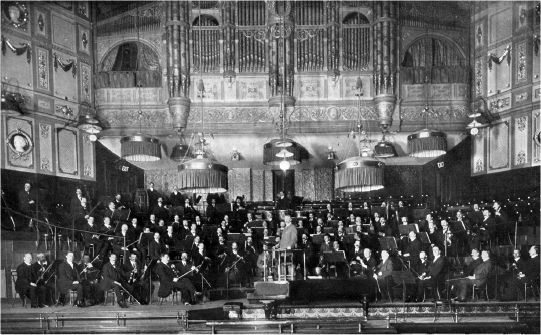

Elgar wanted this to unfurl at the same tempo, but Pappano convinced in his slowing down because he always gets mobile, bel canto phrasing from his players (Abbado would have done that, too, alongside the freedom, if only he’d looked at the Elgar symphonies and fallen in love). Turns and heart-leaps within the rich string writing were always clear; the distinction between violins was all the stronger with the seconds to the right of the conductor. In the vivid music-theatre of this performance, a gauze came down for the summer-night reveries and veiled nightmares in the middle of the first movement. The second was informed by Pappano’s experience of Wagner’s Parsifal – Elgar (pictured above with the LSO in 1911, the year of the Second Symphony's premiere) is always profoundly European, though that observation would be wasted on Brexiters – and a true Elgarian painful inwardness along the way to glory and back.

Elgar wanted this to unfurl at the same tempo, but Pappano convinced in his slowing down because he always gets mobile, bel canto phrasing from his players (Abbado would have done that, too, alongside the freedom, if only he’d looked at the Elgar symphonies and fallen in love). Turns and heart-leaps within the rich string writing were always clear; the distinction between violins was all the stronger with the seconds to the right of the conductor. In the vivid music-theatre of this performance, a gauze came down for the summer-night reveries and veiled nightmares in the middle of the first movement. The second was informed by Pappano’s experience of Wagner’s Parsifal – Elgar (pictured above with the LSO in 1911, the year of the Second Symphony's premiere) is always profoundly European, though that observation would be wasted on Brexiters – and a true Elgarian painful inwardness along the way to glory and back.

The opening lightness of the Rondo, Elgar’s most progressive and fascinating movement, proved deceptive: woodwind shrieked and the ghost from earlier in the symphony, now all hammering juggernaut, came upon us unawares. Pappano kept the more settled mood of the finale’s ceremonials on the move, leapt through its disintegration and stressed the dimming of empire past the middle point before repeating the process and managing the epilogue’s melt into the mists of time to dreamy perfection. His baton-less hand gestures are a miracle in themselves, and always communicate what's there in the music.

He and Znaider could not have been more of one mind in the Beethoven Violin Concerto: why the orchestral opening was so painstakingly shaded became apparent when the soloist leapt to his part not in arrogant command, but out of nothing. Of the many miracles of co-ordination, the violinist-conductor’s response to shadowy orchestral undermining played out in the most magically adjusted of trills, as dramatic a moment as Siegfried's taking the Gibichung’s potion of forgetfulness in Wagner’s Götterdämmerung.

So-called passage-work was simply gossamer spider-web leading from one strong idea to another. Znaider (pictured left by Lars Gundersen) led the not too dreamy Larghetto out in to the light of a poised, ethereal dance, and made no meal of meaty rondo inspiration. The last time I heard this work, in a similarly transformative performance from young violinist Benjamin Baker, we got a rarity in Christian Tetzlaff’s transcription of the cadenzas in Beethoven’s own version for piano, complete with timpani; for Znaider, playing on Kreisler’s Guarnerius ‘del Gesu', it had to be that master’s more familiar cadenzas, woven with the same riveting care and communication as the rest.

So-called passage-work was simply gossamer spider-web leading from one strong idea to another. Znaider (pictured left by Lars Gundersen) led the not too dreamy Larghetto out in to the light of a poised, ethereal dance, and made no meal of meaty rondo inspiration. The last time I heard this work, in a similarly transformative performance from young violinist Benjamin Baker, we got a rarity in Christian Tetzlaff’s transcription of the cadenzas in Beethoven’s own version for piano, complete with timpani; for Znaider, playing on Kreisler’s Guarnerius ‘del Gesu', it had to be that master’s more familiar cadenzas, woven with the same riveting care and communication as the rest.

It had to be Bach for an encore, but not, Znaider announced, the usual Second-Partita Sarabande – the players stamped their feet in genial relief – but the Adagio from the First Partita, similar perfection. Wonderful, then, that the LSO strings matched him for depth, immediacy and musicality. I came back from Prague last week disillusioned that the Philharmonia didn’t sound anything like the Czech Philharmonic, though the conductor was the same (Paavo Järvi). That workaday quality was completely overshadowed by how magnificent the LSO happens to be sounding at the moment. I’ll try not to miss any of their future concerts with either Znaider – who’ll be conducting Tchaikovsky as well as playing Mozart next season – or Pappano.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Add comment