Elle review - sexual violence, black humour and satire | reviews, news & interviews

Elle review - sexual violence, black humour and satire

Elle review - sexual violence, black humour and satire

Isabelle Huppert dazzles in Paul Verhoeven's genre-defying drama

As Elle’s director Paul Verhoeven put it, “we realised that no American actress would ever take on such an immoral movie.” However, Isabelle Huppert didn’t hesitate, and has delivered a performance of such force and boldness that even the disarming Oscar-winner Emma Stone might secretly admit that perhaps the wrong woman won on the night.

But it has to be admitted that Elle (adapted by screenwriter David Birke from Philippe Djian’s novel “Oh...”) could never be mistaken for a Hollywood production. A perplexing but electrifying mixture of sexual violence, black humour and social satire, it might be considered misogynist or voyeuristic or merely in dubious taste, were it not for Huppert’s commanding presence, allied with a batch of supporting performers who mesh smoothly together like a finely-tuned theatrical company.

From the opening, Elle defies you to pin it down to a single genre. Neither Verhoeven – a brazen button-pusher who made Basic Instinct and Showgirls, let's not forget – nor his star are in a mood to take prisoners. We hear, but don’t see, Huppert’s character Michèle Leblanc being attacked and raped by an intruder in her home in the Paris suburbs (Michèle gets a gun, pictured left). Then we see her tidying up the wreckage of her living-room, despite the blood running down her thigh, and getting on with her life as though nothing has happened – no cops and no trauma counselling. Though she does buy some CS spray and learns to fire a pistol.

From the opening, Elle defies you to pin it down to a single genre. Neither Verhoeven – a brazen button-pusher who made Basic Instinct and Showgirls, let's not forget – nor his star are in a mood to take prisoners. We hear, but don’t see, Huppert’s character Michèle Leblanc being attacked and raped by an intruder in her home in the Paris suburbs (Michèle gets a gun, pictured left). Then we see her tidying up the wreckage of her living-room, despite the blood running down her thigh, and getting on with her life as though nothing has happened – no cops and no trauma counselling. Though she does buy some CS spray and learns to fire a pistol.

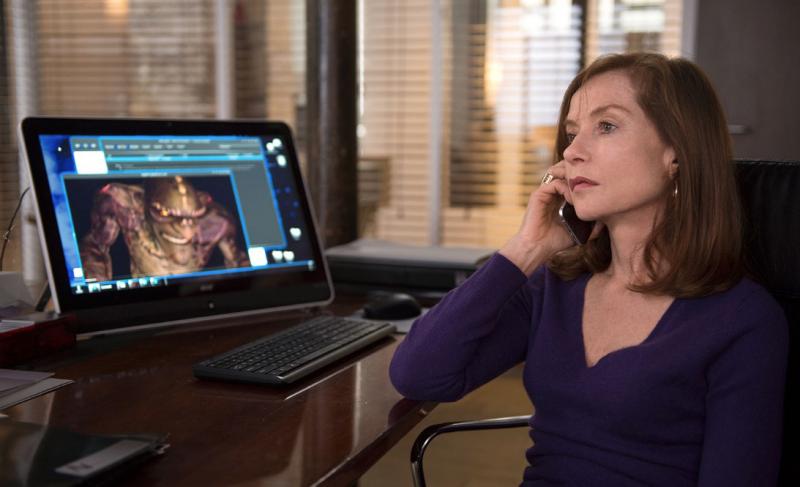

She refuses to play the victim. It seems her private persona is as controlled and inscrutable as the professional face she presents to her employees at the tacky but lucrative computer games company she runs with her close friend Anna (Anne Consigny). Though the team of 20-something designers and programmers who create lurid sex-and-monsters romps regard Anna and Michèle as a pair of old squares, Michèle is happy to spell out with extreme bluntness where their work is falling short and who’s running the company. She demands more on-screen death, sex and titillation.

While Michèle’s mystery attacker – we see him in increasingly startling flashbacks, dressed in a black outfit with a balaclava helmet – keeps up a campaign of creepy and obscene harassment, Verhoeven assembles a picture of the rest of her life, through which she moves with an aura of cool, ironic authority. She knows what she wants, takes it and leaves it. She has a casually friendly relationship with estranged husband Richard (Charles Berling), but like most of the men she knows he’s ineffectual and slightly ludicrous (“their flailing vulnerability is endearing,” as Huppert herself commented). She’s having an affair with Robert (Christian Berkel), but her emotional investment in it is zero. She impatiently does her best to put up with her son Vincent (Jonas Bloquet), a gormless under-achiever shackled to a hysterical tantrum-throwing girlfriend (Alice Isaaz). When the latter has her baby, Vincent ludicrously can’t bring himself to accept that the child is black, unlike its supposed parents.

The only man who truly piques Michèle’s sexual interest is Patrick (Laurent Lafitte, pictured right with Huppert), a handsome, successful banker, who has moved into the house opposite hers with his wife Rebecca (Virginie Efira). In several raucous dinner and party scenes, Verhoeven makes plenty of space for his excellent cast to cut loose with abandon, and when Michèle throws a Christmas party she seizes the opportunity to flirt outrageously with Patrick. Meanwhile, much macabre comedy is extracted from Michèle’s toxic relationship with her mother Irène (Judith Magre), a grotesque plastic surgery junkie with a weakness for gold-digging gigolos.

The only man who truly piques Michèle’s sexual interest is Patrick (Laurent Lafitte, pictured right with Huppert), a handsome, successful banker, who has moved into the house opposite hers with his wife Rebecca (Virginie Efira). In several raucous dinner and party scenes, Verhoeven makes plenty of space for his excellent cast to cut loose with abandon, and when Michèle throws a Christmas party she seizes the opportunity to flirt outrageously with Patrick. Meanwhile, much macabre comedy is extracted from Michèle’s toxic relationship with her mother Irène (Judith Magre), a grotesque plastic surgery junkie with a weakness for gold-digging gigolos.

Storm clouds gather, however, when Michèle finds herself drawn into a potentially fatal cat-and-mouse game with her attacker. As events gather pace towards an explosive climax, her motivations become darker and knottier. Is she planning an elaborate revenge, or does she genuinely relish being beaten and violated? Perhaps the fact that her father was a notorious serial-killer from the 1970s has left her with catastrophic psychological damage… or perhaps there’s more of her father in her than she can bear to acknowledge. Verhoeven isn’t going to spell it out, and Michèle will only live in the present and refuses to dwell on the past. We have to form our own judgments. Isn’t that the way it should be?

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Elle

As Elle’s director Paul Verhoeven put it, “we realised that no American actress would ever take on such an immoral movie.” However, Isabelle Huppert didn’t hesitate, and has delivered a performance of such force and boldness that even the disarming Oscar-winner Emma Stone might secretly admit that perhaps the wrong woman won on the night.

But it has to be admitted that Elle (adapted by screenwriter David Birke from Philippe Djian’s novel “Oh...”) could never be mistaken for a Hollywood production. A perplexing but electrifying mixture of sexual violence, black humour and social satire, it might be considered misogynist or voyeuristic or merely in dubious taste, were it not for Huppert’s commanding presence, allied with a batch of supporting performers who mesh smoothly together like a finely-tuned theatrical company.

From the opening, Elle defies you to pin it down to a single genre. Neither Verhoeven – a brazen button-pusher who made Basic Instinct and Showgirls, let's not forget – nor his star are in a mood to take prisoners. We hear, but don’t see, Huppert’s character Michèle Leblanc being attacked and raped by an intruder in her home in the Paris suburbs (Michèle gets a gun, pictured left). Then we see her tidying up the wreckage of her living-room, despite the blood running down her thigh, and getting on with her life as though nothing has happened – no cops and no trauma counselling. Though she does buy some CS spray and learns to fire a pistol.

From the opening, Elle defies you to pin it down to a single genre. Neither Verhoeven – a brazen button-pusher who made Basic Instinct and Showgirls, let's not forget – nor his star are in a mood to take prisoners. We hear, but don’t see, Huppert’s character Michèle Leblanc being attacked and raped by an intruder in her home in the Paris suburbs (Michèle gets a gun, pictured left). Then we see her tidying up the wreckage of her living-room, despite the blood running down her thigh, and getting on with her life as though nothing has happened – no cops and no trauma counselling. Though she does buy some CS spray and learns to fire a pistol.

She refuses to play the victim. It seems her private persona is as controlled and inscrutable as the professional face she presents to her employees at the tacky but lucrative computer games company she runs with her close friend Anna (Anne Consigny). Though the team of 20-something designers and programmers who create lurid sex-and-monsters romps regard Anna and Michèle as a pair of old squares, Michèle is happy to spell out with extreme bluntness where their work is falling short and who’s running the company. She demands more on-screen death, sex and titillation.

While Michèle’s mystery attacker – we see him in increasingly startling flashbacks, dressed in a black outfit with a balaclava helmet – keeps up a campaign of creepy and obscene harassment, Verhoeven assembles a picture of the rest of her life, through which she moves with an aura of cool, ironic authority. She knows what she wants, takes it and leaves it. She has a casually friendly relationship with estranged husband Richard (Charles Berling), but like most of the men she knows he’s ineffectual and slightly ludicrous (“their flailing vulnerability is endearing,” as Huppert herself commented). She’s having an affair with Robert (Christian Berkel), but her emotional investment in it is zero. She impatiently does her best to put up with her son Vincent (Jonas Bloquet), a gormless under-achiever shackled to a hysterical tantrum-throwing girlfriend (Alice Isaaz). When the latter has her baby, Vincent ludicrously can’t bring himself to accept that the child is black, unlike its supposed parents.

The only man who truly piques Michèle’s sexual interest is Patrick (Laurent Lafitte, pictured right with Huppert), a handsome, successful banker, who has moved into the house opposite hers with his wife Rebecca (Virginie Efira). In several raucous dinner and party scenes, Verhoeven makes plenty of space for his excellent cast to cut loose with abandon, and when Michèle throws a Christmas party she seizes the opportunity to flirt outrageously with Patrick. Meanwhile, much macabre comedy is extracted from Michèle’s toxic relationship with her mother Irène (Judith Magre), a grotesque plastic surgery junkie with a weakness for gold-digging gigolos.

The only man who truly piques Michèle’s sexual interest is Patrick (Laurent Lafitte, pictured right with Huppert), a handsome, successful banker, who has moved into the house opposite hers with his wife Rebecca (Virginie Efira). In several raucous dinner and party scenes, Verhoeven makes plenty of space for his excellent cast to cut loose with abandon, and when Michèle throws a Christmas party she seizes the opportunity to flirt outrageously with Patrick. Meanwhile, much macabre comedy is extracted from Michèle’s toxic relationship with her mother Irène (Judith Magre), a grotesque plastic surgery junkie with a weakness for gold-digging gigolos.

Storm clouds gather, however, when Michèle finds herself drawn into a potentially fatal cat-and-mouse game with her attacker. As events gather pace towards an explosive climax, her motivations become darker and knottier. Is she planning an elaborate revenge, or does she genuinely relish being beaten and violated? Perhaps the fact that her father was a notorious serial-killer from the 1970s has left her with catastrophic psychological damage… or perhaps there’s more of her father in her than she can bear to acknowledge. Verhoeven isn’t going to spell it out, and Michèle will only live in the present and refuses to dwell on the past. We have to form our own judgments. Isn’t that the way it should be?

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Elle

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

Add comment