The heart of the V&A’s sumptuous Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams is a room dedicated to the workmanship of the fashion house’s ateliers. A mirrored ceiling reflects dazzling strip-lit cases which hold the ghosts of ballgowns, slips and jackets — adjusted prototypes, haute couture maquettes — made in white toile by the seamstresses of Dior’s Paris studios before they begin work on the final garment. The pieces tower overhead, stacked in an apparently infinite iteration of shoulders, waists and necklines, cuffs. Over here’s a grouping with jester fastenings, over there, jerkin variations. At ground level, a gown from 2007 which swept along the runway impudently crystal-spangled and sashed in royal blue is stripped to pale ligature.

The room’s focus on tailored form strips away the distraction of texture and colour and casts into sharp relief the six key creative directors who have taken successive charge since Christian Dior’s sudden death in 1957. Yves Saint Laurent was first at the helm before handing over to Marc Bohan who steered the house through the 60s, 70s and 80s. The 90s marked an extravagant turn, with architecturally-trained flâneur Gianfranco Ferré ushering in an era of flair only for the ante to be ramped up by preternatural wunderkind and sartorial bad boy John Galliano. In the turbulence that followed his ignominious firing for a drunken anti-semitic rant (for which he has made significant amends) and the widely-panned stopgap tenure of Bill Gaytten (quietly passed over), Raf Simons reestablished Dior on a footing of modernist elegance. This has been carried over by current director Maria Grazia Chiuri, whose meticulous eye has challenged even the ateliers’ expertise by incorporating intensive, historically-informed techniques (such as velours au sabre in which the top warp of silk is cut thread by thread to give a velvety finish) and reconfigured the female silhouette.

The room’s focus on tailored form strips away the distraction of texture and colour and casts into sharp relief the six key creative directors who have taken successive charge since Christian Dior’s sudden death in 1957. Yves Saint Laurent was first at the helm before handing over to Marc Bohan who steered the house through the 60s, 70s and 80s. The 90s marked an extravagant turn, with architecturally-trained flâneur Gianfranco Ferré ushering in an era of flair only for the ante to be ramped up by preternatural wunderkind and sartorial bad boy John Galliano. In the turbulence that followed his ignominious firing for a drunken anti-semitic rant (for which he has made significant amends) and the widely-panned stopgap tenure of Bill Gaytten (quietly passed over), Raf Simons reestablished Dior on a footing of modernist elegance. This has been carried over by current director Maria Grazia Chiuri, whose meticulous eye has challenged even the ateliers’ expertise by incorporating intensive, historically-informed techniques (such as velours au sabre in which the top warp of silk is cut thread by thread to give a velvety finish) and reconfigured the female silhouette.

Through eleven rooms, distinctions are drawn between how each director has understood the female form. A trio of jackets designed by Chiuri (2018) tops three by Galliano, (from 2010 and 2009). Where Galliano’s hems excitedly surf the hipline to accentuate dramatically cinched waists, sculpted shoulders and bold shawl collars, Chiuri’s longer panels settle smooth length along the torso and find volume in choir boy sleeves — a mediaeval refrain picked up with pleated rope belts and collarless necklines. Elsewhere, in a room dedicated to Dior’s love of horticulture, Galliano’s bombastic tulip dresses and hyacinth skirts turn women into flowers (Look 19 and Look 3 Ensemble, A/W 2010) while Chiuri’s Garden Fleuri Dress, S/S 2017 pays homage to Raf Simon’s Look 47 Dress, A/W 2012: his demure and tightly packed chiffon buds are blown into blooms of dyed feathers, his ankle-skimming hem is loosely riffed in dreamy layers of translucent floor-length silk, and his formal strapless bodice lent a flirtatious, fairytale edge with an arrow-plunged neckline and slender shoulder straps. While Galliano’s sartorial daring could turn women into flowers — performers of their womanhood — the appeal of Chiuri’s designs lies in hallucinatory attention to decorative finish and close cuts that derive their force from the forms of the women who wear them.

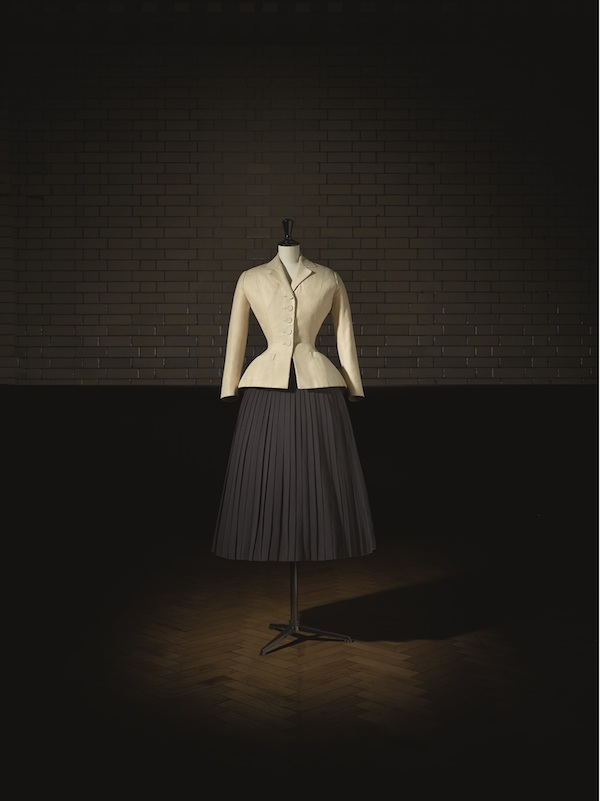

While it is tempting to pit different directors against each other in battles of preference, both technical experimentation and a taste for theatricality are unifying features. The exhibition opens with the iconic — and controversial — Bar suit (pictured right). This well-preserved example drawn from the V&A’s own collection is flanked by homages by Ferré, Chiuri and Galliano which defer to the founder while also speaking of their own era — Ferré’s magnificent 1991 kimono sleeves, Galliano’s inspired 1997 pairing of crocodile leather and fringed wool, Chiuri’s opinion-splitting We should all be feminists t-shirt from 2017. When in 1947 the “New Look” premiered in London, journalist Ernestine Carter described how at the “positively voluptuous” sight of soft-shouldered, nipped-waist models swinging round the salon in extravagant reams of black wool, the ration-hit English women could be seen “tugging at their skirts trying to inch them over their knees”. It also provoked sharp comment from future prime minister Harold Wilson in his role at the Board of Trade as rationing was still in force.

While it is tempting to pit different directors against each other in battles of preference, both technical experimentation and a taste for theatricality are unifying features. The exhibition opens with the iconic — and controversial — Bar suit (pictured right). This well-preserved example drawn from the V&A’s own collection is flanked by homages by Ferré, Chiuri and Galliano which defer to the founder while also speaking of their own era — Ferré’s magnificent 1991 kimono sleeves, Galliano’s inspired 1997 pairing of crocodile leather and fringed wool, Chiuri’s opinion-splitting We should all be feminists t-shirt from 2017. When in 1947 the “New Look” premiered in London, journalist Ernestine Carter described how at the “positively voluptuous” sight of soft-shouldered, nipped-waist models swinging round the salon in extravagant reams of black wool, the ration-hit English women could be seen “tugging at their skirts trying to inch them over their knees”. It also provoked sharp comment from future prime minister Harold Wilson in his role at the Board of Trade as rationing was still in force.

Yet for all the apparent excess, Dior was a quiet, if humorous, man who as a designer could combine subtle provocation with decorative invention. His gown for Princess Margaret’s 21st birthday celebration (pictured above left) was embroidered with both straw and mother of pearl — a striking combination noted with interest by Chiuri as she tours the cases, adding that for environmental reasons, nacre can no longer be used. She is equally taken with the exquisite tailoring of the triple-collared Nonette ensemble, which stands next to a Daisy suit. The latter was bought by 21 clients, including Nancy Mitford and Margot Fonteyn, and highlights the commercial nous on which Dior founded the fashion house — which by 1955 accounted for over half of French exports of haute couture. To compound his early success, Dior swiftly opened in London, New York, Caracas and Mexico, and established lines of ready-to-wear garments and accessory lines including perfume, gloves, shoes and jewellery which were sold at high-end department stores. As the favoured couturier of stars, this cannily made Dior creations accessible to women for whom the bespoke service was out of reach — gloves afforded a taste of the luxury so sought by Hollywood actresses and royalty. The double tradition has endured. When Diorshow mascara launched in 2002 it drew almost universal acclaim from make-up professionals and developed a devoted following of general consumers; and in the final, superlative room dedicated to Dior gowns, a parade of creations as sumptuous as they are timeless is footnoted by the famous women who have worn them: Rihanna, Princess Diana, Zhang Ziyi, Lupita Nyong’o, and Emma Watson (Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is shown beaming from a magazine cover in an earlier room, wearing one of Chiuri’s slogan t-shirts inspired by her essay).

Of course, I, like many others, can only dream of a Dior gown or the occasion to wear one. But the exhibition is stunning. There’s a dress of tessellated sequinned eyes, an Anubis-headed snake suit, a mink-collar coat and a gold lamé trouser suit. From glamorous to inventive, sensuous to outrageous, they’re a feast for the eye. Long-standing Dior milliner, Stephen Jones, deserves a mention for his fabulous confections — but the last word goes to the workmanship, craft and devotion dedicated to these creations, the thousands of hours and an incantatory array of materials: crystals, silk, crêpe, ostrich feathers, satin, chiffon, wool, metal thread, lamé, gold, python leather, organdie, organza, pearls, melanex, velvet, mother-of-pearl, faille, sequins, guipure lace, moiré silk, damask, rabbit fur, chenille, net, sheepskin, plastic, charmeuse silk, feathers, resin, acetate, tulle, taffeta, grosgrain, chiffon, shantung — it’s utterly hypnotic.

- Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams is at the V&A from 2nd February - 14th July 2019. Tickets £20-24, concessions £15

- Read more visual art reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment