The release of Matthew Heineman’s film A Private War, about the tumultuous life and 2012 death of renowned Sunday Times war correspondent Marie Colvin, has gained an added edge of newsworthiness from this week’s verdict by Washington DC’s US District Court for the District of Columbia. Judge Amy Jackson ruled that Colvin’s death in the besieged city of Homs was “an extrajudicial killing” by the Syrian government. Bashar al-Assad’s administration has been ordered to pay $300m in punitive damages, as well as compensation to Colvin’s sister Cathleen. It may take an intervention by the US Marines to collect it, though.

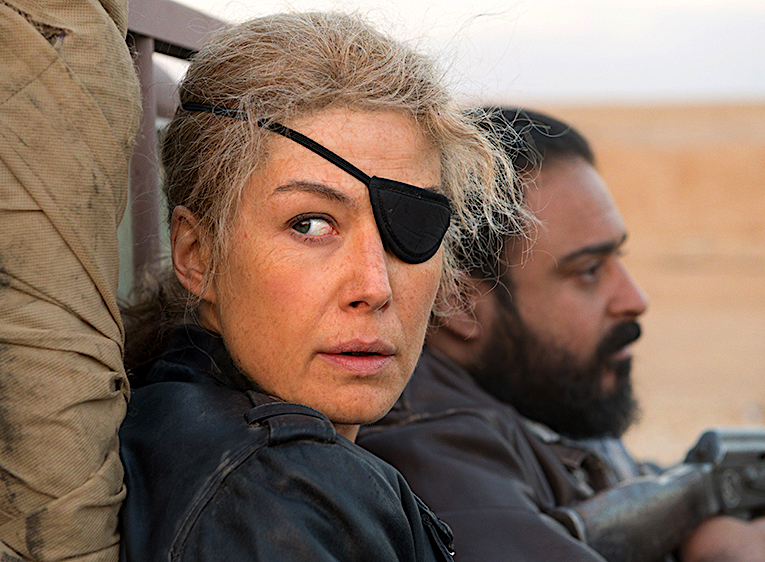

Heineman calls his film “a psychological portrait”, with Rosamund Pike taking on the daunting challenge of the Colvin role, and it covers the last decade of Colvin’s life as she strode boldly into horrific conflicts in Sri Lanka (where she lost an eye in a rocket-propelled grenade explosion), Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan and Syria. Her work brought her prestigious professional awards, but also wreaked havoc with her emotional life and caused her to be treated for PTSD. Heineman was aiming to explore “the paradoxical swirl of addictions that made Marie brilliant, but also increasingly tortured”.

It’s Heineman’s first drama, or “narrative film” as he puts it, but he has racked up an impressive track record in documentaries. His previous film, City of Ghosts (2017), told the story of the Syrian citizen-journalists who covered the takeover of Syria by ISIS in 2014. Cartel Land (2015) focused on Mexico’s drug gangs and the vigilante groups which had sprung up to combat them, and won three Primetime Emmy awards and an Academy Award nomination. His acclaimed 2018 TV series The Trade covered America’s opioid epidemic from all angles.

He told theartsdesk about the challenges and emotional demands of making A Private War.

He told theartsdesk about the challenges and emotional demands of making A Private War.

ADAM SWEETING: How did it feel moving into drama after previously making documentaries?

MATTHEW HEINEMAN: It was great, I felt very fortunate to be able to tell this story, that people believed in me to make this leap, and I felt very moved and motivated to make this film. It’s a very personal film for me. For me, it’s not just an homage to Marie, but it's an homage to journalism and to people who are out there fighting for the truth and shedding light in dark corners of the world. I think that message is more important than ever right now, with journalism and journalists under attack.

How aware were you of Marie Colvin? (pictured above)

I knew who she was, she’s obviously a legend in the field of journalism. I didn’t know her personally. When I came on board there was already an early draft of a script, and then I spent about a year doing research. Reading everything I could about her, reading everything I could that she wrote, gaining the trust of her friends and colleagues. Through that process I dug in with our writer Arash Amel to reconstruct the script to be much more of a sort of psychological thriller, if you will, about what really drives somebody to go to the most dangerous places on earth to tell these stories, and then the effects that that had on her mentally and physically.

She must have been aware that it was destroying her in some ways. What keeps someone going in those circumstances?

I think many things. I think she felt despite every sign in the world saying "Stop, stop, stop", I think she felt compelled to tell these stories because she felt that no-one else would. I think she felt compelled to take these very complex geopolitical conflicts and try to humanise them in a way to get people to care as much as she did. To try to take these places that people keep at arm’s length and to make them feel like they’re as relevant and important as the daily news cycle. I don’t think Marie was a war junkie. There’s sort of the cliched idea that war reporters are adrenalin junkies, and she was not. She was filled with fear, she was not fearless. She hated being in the front lines. For her it was always about the stories of the people, that’s what drove her.

You’ve made films about drug cartels and ISIS. The danger and menace must be quite familiar to you?

You’ve made films about drug cartels and ISIS. The danger and menace must be quite familiar to you?

Yeah, I think that’s another reason why I made the film, which is that I felt that same draw to covering conflict zones. Some of that same bizarre feeling of coming home and having those thoughts and images linger inside of you. So yeah, I deeply empathised, I guess, with her experience.

It seems Rosamund Pike (pictured above) made a huge commitment to playing the role?

She did a phenomenal job, it was amazing working with her. And when we first met, after the screening of my last documentary City of Ghosts, the passion and vigour with which she wanted the role, it almost seemed like it was Marie going after an article. And I really wanted to find somebody who was (a) going to get their hands dirty and (b) sort of treat me as an equal, since it was my first narrative film, and I got both of those things in spades. She spent months and months and months preparing with a dialect coach, she’s obviously from London and Marie was from Long Island in New York. Her voice was almost an octave lower, with this deep whisky tone. Ros spent months with a dancing coach understanding how Marie carried herself and held tension in her neck and splayed her hands when she gesticulated, and she worked with a tutor to understand the various geopolitical conflicts. Not that that’s what the film is about, but she just wanted to know. It was remarkable to see her really transform into this person.

Was wearing the eye patch a problem for her?

Yeah, it was hard. I mean, it’s not easy – walk around for half an hour covering one eye, it totally changes your perception of dimensions. Also Ros is so talented with her eyes and she emotes so much through her eyes that I was taking one of them away from her, so she had to do all that work with one eye. But that was also a strength, the way she tilts her head and used that one eye to convey emotion and feeling.

Tom Hollander (pictured right, playing Sunday Times foreign editor Sean Ryan) did know Marie Colvin, I think?

Tom Hollander (pictured right, playing Sunday Times foreign editor Sean Ryan) did know Marie Colvin, I think?

Yes, he did know her a bit, and I think they had lunch not too long before she was killed, and actually joked around about making a film about her life. So I think he was quite moved when asked about doing the film, it was quite personal for him as well, obviously in a different way. That relationship between an editor and a correspondent was really fascinating to me and I didn’t want to just make it one-dimensional. It’s such a deeply subtle and complex relationship, one in which they both need a scoop, one in which they need that story. Marie is the one going out and risking her life, Sean is the one staying in London and going home to his family every night. At the end of the day they also cared deeply for each other, so exploring those different subtleties was really important for Tom and for that relationship between Sean and Marie in the film.

How did you cast Jamie Dornan (pictured below) as photographer Paul Conroy, who works very well as a counterpoint to her?

He was phenomenal, and I think it’s such an understated role. The real Paul Conroy is quite a funny, goofy, humble guy, and that’s who Jamie is as well. When I first met Jamie I almost felt like I saw Paul, without him even acting. He also had to transform into that role. Jamie is Irish and Paul is from Liverpool, and to get that accent which to me as a dumb American sounds quite similar but is quite different was much scarier than doing like an American accent or something that was totally different. The big question was would Jamie be okay with having Paul on set. Actors go both ways on that. Some are inspired and love it and some just don’t want to have the pressure of having the person there. Anyway, they got along quite well. Paul was supposed to be there for four or five days as a consultant for the film, and he ended up never leaving. He was a huge inspiration to Jamie, to Ros, to me and to the whole film. Paul was really helpful in getting a lot of the details right.

You cast a lot of local people who’d suffered in the Syrian war, didn’t you?

You cast a lot of local people who’d suffered in the Syrian war, didn’t you?

I worked with largely non-actors, refugees living in Jordan, for the background cast in the various war zones, so that when Marie walks into the widows’ basement in Syria, in the besieged city of Homs, the women that Rosamund’s speaking to are real women from Homs, telling their own real stories, shedding real tears. And that second woman, when she says "I don’t just want this to be words on paper, I want the whole world to understand what we’re going through", that’s her speaking to Ros, but that’s her speaking to all of us. And it made for a very emotional set. The scene in the hospital, the man who brings in the young boy who ends up dying and is broadcast on Anderson Cooper on CNN, he is also from Homs. His two-year-old nephew was shot off his shoulders at a protest in Homs and died, bled out in front of him, and so the grief and the trauma that he brought onto that set was almost unbearable. At one point Rosamund walked off set and was, like, "I don’t know how to handle all this, the lines between documentary and fiction are so blurred." And I said to her, look, this is something that I deal with on a daily basis in my documentary work, you have this human instinct to want to give someone a hug or to give them space, but your job is to capture these moments as it was Marie’s. And we’re not exploiting him, he wouldn’t be here if he didn’t want this story to be told. And there are many examples of that throughout the film.

The scene when Norm Coburn, the American photographer, has been killed is very intense.

Yeah, he was a mirror to Marie’s mortality, and she sees herself obviously in Norm. The real potential that this is a life-or-death game, and she was constantly skirting around that red line of pushing the envelope on danger.

Do you think people will be inspired to do that kind of work if they see this film?

I think a lot of people who’ve seen the film have been inspired not necessarily to do that type of work – it’s a very specific type of person who goes out and puts their life on the line every day to tell stories – but I think people find general inspiration in what Marie stood for. She lived a life with huge consequences but with great purpose, and such a clear sense of what she wanted. There were many things in her life that weren’t clear. Many things in her life that troubled her. But when it came to work, she was so clear with what she wanted to do and what she needed to do and what she felt compelled to do, and I think a lot of us are trying to find that purpose and that drive.

For one night only, Q&A with Rosamund Pike, Jamie Dornan, Paul Conroy and Matthew Heineman, broadcast live to cinemas on 4 February. Book Tickets at aprivatewar.film. A Private War is on general release on 15 February