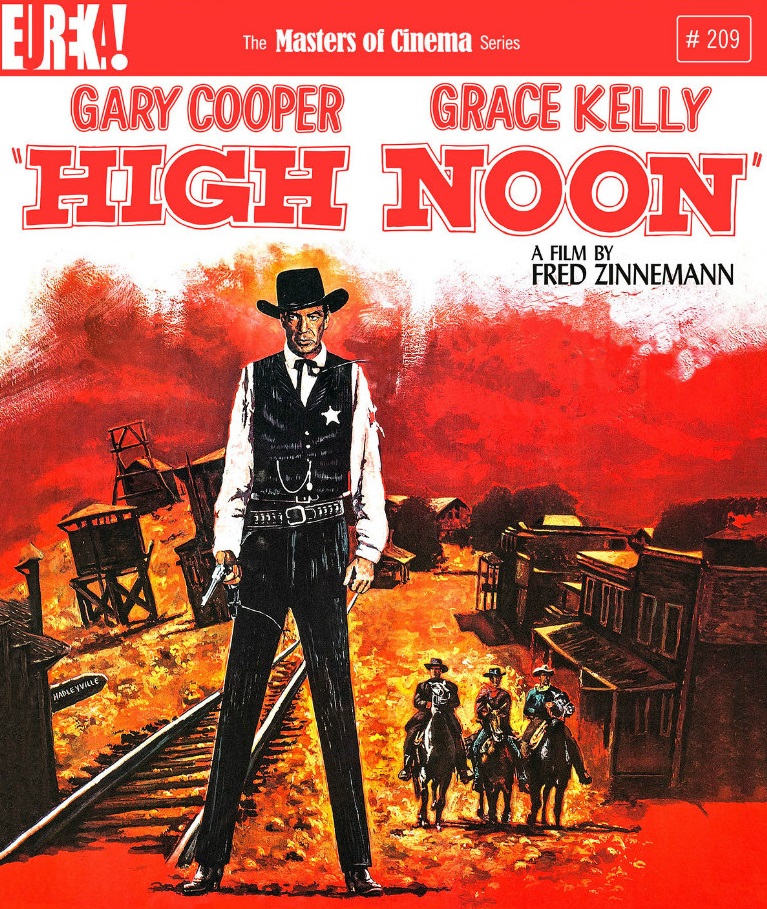

The canonical town-taming Western High Noon brought Gary Cooper the 1952 Academy Award for Best Actor (his second). It also won Oscars for Best Editing, Best Score, and Best Song, Dimitri Tiomkin and Ned Washington’s “Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darlin’” – throbbingly sung by Tex Ritter, whose voice combines with ticking clocks and real-time pacing to make Fred Zinnemann’s film unbearably tense.

But for the rabid anti-Communist campaigning of Hollywood hawks like John Wayne and columnist Hedda Hopper, High Noon might have also claimed Oscars for nominees Zinnemann, producer Stanley Kramer (Best Picture), and screenwriter Carl Foreman, a friend and partner in Kramer’s independent production company.

Foreman was writing the film at the time of the second McCarthy witch-hunt in Hollywood and was forced to testify before the House UnAmerican Activities Committee. He admitted to being a disillusioned former Communist Party member 10 years previously but refused to name names; Wayne met with Foreman in person and tried, in vain, to persuade him to cooperate. Kramer subsequently bought out Foreman as a partner and removed him as High Noon’s associate producer, but not before Foreman had reworked the script as a full-blown allegory of McCarthyism.

Foreman was writing the film at the time of the second McCarthy witch-hunt in Hollywood and was forced to testify before the House UnAmerican Activities Committee. He admitted to being a disillusioned former Communist Party member 10 years previously but refused to name names; Wayne met with Foreman in person and tried, in vain, to persuade him to cooperate. Kramer subsequently bought out Foreman as a partner and removed him as High Noon’s associate producer, but not before Foreman had reworked the script as a full-blown allegory of McCarthyism.

“As I was writing the screenplay, it became insane, because life was mirroring art and art was mirroring life,” Foreman recalled. “It was all happening at the same time. I became that guy. I became the Gary Cooper character.” Glenn Frankel, author of High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic, contributes an audio commentary to this Eureka! label release in which he explains how the conservative Republican Cooper tried to support Foreman after High Noon was completed by investing in a production outfit he was forming. In the event, Foreman’s enemies pressured Cooper to withdraw from the venture and Foreman re-located to England.

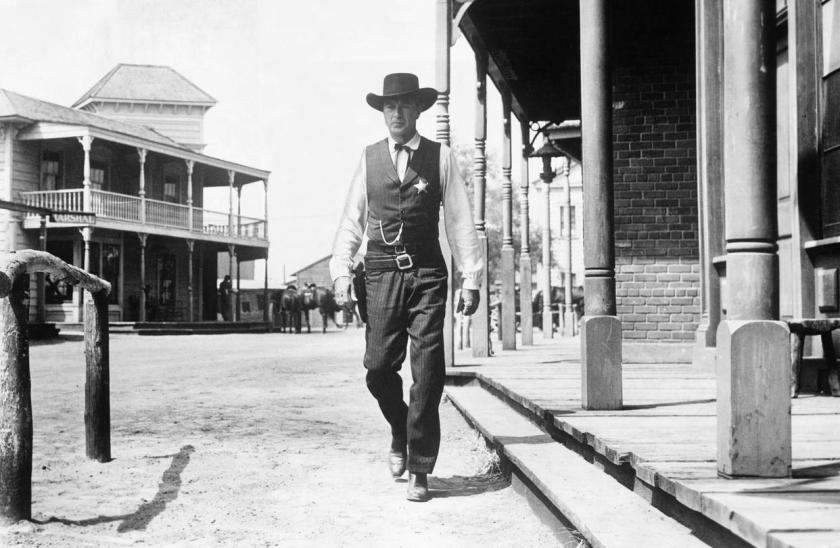

Hampered by an ulcer and personal upheaval during High Noon’s 32-day production, Cooper never looked as gaunt, haggard, and scared – yet resolute – as he did playing Will Kane, the morally principled marshal, who, deserted by his anti-violence Quaker bride Amy (Grace Kelly) and every able-bodied man in the New Mexico town of Hadleyville, decides to make a lone stand against four gunmen. He cannot abandon people he has long protected; he knows, in any case, that his foes will kill him and rape and kill Amy if they catch them on the prairie.

This spineless crew represents the career-minded and cowardly friends and colleagues who had spurned Foreman in his hour of need

The gunmen are led by the pardoned killer Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald), who intends to resume control of the town once he has killed Kane for arresting him five years previously, as well as the judge (Otto Kruger) who had sentenced him to hang. Kane may be honourable, but he is as capable of dealing death as Miller; they are linked as the ex-lovers of Helen Ramirez (Katy Jurado), the self-made Mexican saloon-owner (and presumably brothel-keeper) who tells her current flame, Kane’s selfishly ambitious young deputy Harvey Pell (Lloyd Bridges), that he cannot match Kane for manliness, thus equating virility and nobility. The quartet of righteous gunfighter, virtuous white woman, decadent killer, and sexualised Mexican woman was familiar from the William S Hart Western Hell’s Hinges (1916) and John Ford’s My Darling Clementine (1946).

As the clocks eat away the minutes to noon, which will bring Miller back to Hadleyville and carry Amy away, the judge flees, Pell and a citizen deputy hand in their badges, Kane’s best friend (Harry Morgan) hides behind his wife, and the mayor (Thomas Mitchell) urges the men gathered in church that Sunday morning to stay behind doors lest mass killing deters northern investment in the “progressive” burg. This spineless crew represents the career-minded and cowardly friends and colleagues who had spurned Foreman in his hour of need. Only a boy and a drunk are ready to fight alongside Kane but, knowing they’d die, he gently rebuffs them. The train arrives and the shooting starts. Kane does find an ally at the last. That wasn’t good enough for Wayne, who reviled High Noon as “un-American” and collaborated with director Howard Hawks on the making of the 1959 riposte Rio Bravo (1959), which depicts a communal defence of a town led by an unflinching sheriff.

High Noon is more resonant than Rio Bravo because it is better constructed than because it appeals to liberal sensibilities. There is a sense, anyway, that High Noon is multivalent, that Kane might as easily be a HUAC investigator (like Wayne in 1952’s Big Jim McClain) smashing Communist infiltrators as a man of conscience confronting right-wing thugs. Kane’s imposing of rugged individualism and the code of violence over the rule of democracy is troubling; he anticipates Clint Eastwood’s spaghetti Western vigilantes.

Yet the sight of Cooper’s bruised, bloodied marshal walking his lonely walk along Hadleyville’s main street doesn’t suggest ideological symbolism: he is simply an isolated man, a reluctant hero, obliged to fight to save the townsfolk, his wife, and himself. Though Alan Ladd’s courtly gunfighter in Shane is a more mythical figure than Kane, George Stevens’s analogous 1953 classic makes the viewer much more aware of its farmers-versus-cattle-ranchers class warfare theme than High Noon does of its witch-hunt allegory.

Graced by Floyd Crosby’s elegant black-and-white cinematography, which imparts a newsy, polemical charge (a hallmark, too, of Henry King’s 1950 The Gunfighter), High Noon has been handsomely restored in 4K for its first British Blu-ray release; watch out for Crosby's stunning close-ups. As well as Frankel’s commentary, there is a commentary by film scholar Stephen Prince, a video interview with Zinnemann expert Neil Sinyard, a 1969 audio interview with Foreman, a High Noon documentary and two video pieces, and a limited edition 100-page booklet.

Add comment