'Divinity is all around us': soprano Susanna Hurrell on Ravi Shankar's 'Sukanya' | reviews, news & interviews

'Divinity is all around us': soprano Susanna Hurrell on Ravi Shankar's 'Sukanya'

'Divinity is all around us': soprano Susanna Hurrell on Ravi Shankar's 'Sukanya'

Celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Indian master's birth with a return to his opera

In 2010, my best friend and I made a whimsical decision to go backpacking in India over the Easter break. I had developed an interest in Eastern philosophy through exposure to the teachings of the ancient Vedas, and through the practice of Transcendental Meditation, so I jumped on the opportunity to experience the culture that gave birth to so much wisdom and ancient knowledge.

I went with stars in my eyes and was shocked to discover it was nothing like the romantic India of my imagination. It was louder, more aggressive, more heavily polluted and far more chaotic. On our first night, in a run down hotel, listening to the incessant song of the pigeon who shared our room, and watching sparks fly from the hundreds of cables which crossed over the street, we fell about in hysterical laughter and realised that we were on a rollercoaster that wasn’t going to stop so we’d have to let go of our resistance and enjoy the ride. It was a wonderful adventure and there were jewels to be found within the madness, so it wasn’t long before I fell in love with India again but this time with the reality, rather than with my imagined version.

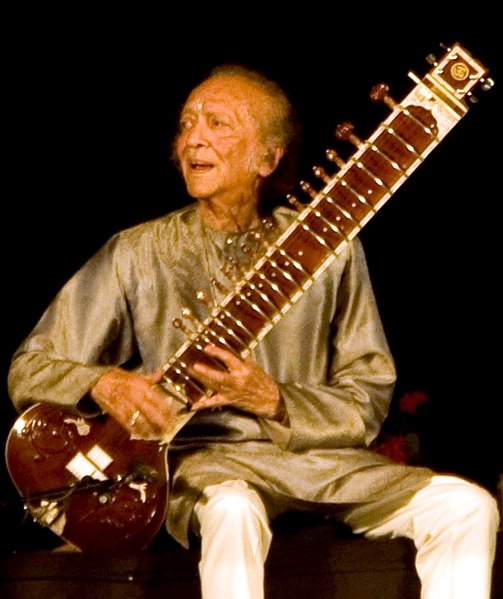

When I was asked to play the role of Sukanya several years later, I was excited because of my connection with India - I’d been back there with my singing teacher, Patricia Rozario, for a singing tour - but I also wondered if perhaps I might now find something more spiritual through the medium of Indian classical music. I could see that David Murphy, who was leading the project, had a great deal of passion for it, and a huge respect for his guru, and composer of the work, the legendary Ravi Shankar (pictured right performing with his daughter Anoushka in 2009).

When I was asked to play the role of Sukanya several years later, I was excited because of my connection with India - I’d been back there with my singing teacher, Patricia Rozario, for a singing tour - but I also wondered if perhaps I might now find something more spiritual through the medium of Indian classical music. I could see that David Murphy, who was leading the project, had a great deal of passion for it, and a huge respect for his guru, and composer of the work, the legendary Ravi Shankar (pictured right performing with his daughter Anoushka in 2009).

Learning the music wasn’t easy. David taught us the Indian scale, which is the equivalent of our Solfeggio scale only with different tuning, and different syllables - Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Dha Ni Sa. It comes from the harmonics of a single drone, and is therefore a very natural sequence of pitches, though to western classically trained ears it can sound slightly odd. We were encouraged to improvise with the scale and learn it to the point where we could create each note in the present, rather than remembering the written phrases.

When I met the Indian musicians I had the sensation that they were somehow aiming to lose themselves through their playing. One particular man, sweet and deferential in person, seemed to have bright lights shining from his eyes when he played, not unlike the lights of Chyavana’s eyes that Sukanya spies beaming out from under the anthill. He seemed to become an empty vessel through which a divine flow of music was being poured. His hands worked fluently and with lightness and his connection with the other musicians seemed telepathic. Before they perform, the Indian musicians and dancers have a ritual of bending down to touch the stage, as if for good luck, but not in the sense of needing luck for themselves, more like a humble invitation for the divine muse to reveal itself in the space. [Susanna Hurrell pictured above by Harry Livingstone.]

Before they perform, the Indian musicians and dancers have a ritual of bending down to touch the stage, as if for good luck, but not in the sense of needing luck for themselves, more like a humble invitation for the divine muse to reveal itself in the space. [Susanna Hurrell pictured above by Harry Livingstone.]

The piece touches on this union of the divine in sync with the human experience. It is expressed in the story from the Mahabharata and also through the music lesson scene which is based on Ravi Shankar’s own lessons, where the notes played on the tanpura take off and appear to fly of their own accord.

In Sukanya’s final trial, the reckless Aswini twin demigods attempt to woo her away from her old, blind husband with their message of youth. Sukanya is determined to resist them, fully devoted to loving her husband, despite admitting that he is no lotus flower. They offer her the chance to restore her husband’s youth and eyesight if she can recognise him after they transform him into their identical triplet. Chyavana overhears and accepts this ‘diversion’ on behalf of Sukanya, trusting in her to choose him. It is a tense moment, reminiscent of the trials of The Magic Flute, but love wins: she holds in her heart the phrase, “He walks on earth”, and suddenly recognises in his face alone an earthly quality. Singing their final love song to each other, they reaffirm their mutual devotion:

In Sukanya’s final trial, the reckless Aswini twin demigods attempt to woo her away from her old, blind husband with their message of youth. Sukanya is determined to resist them, fully devoted to loving her husband, despite admitting that he is no lotus flower. They offer her the chance to restore her husband’s youth and eyesight if she can recognise him after they transform him into their identical triplet. Chyavana overhears and accepts this ‘diversion’ on behalf of Sukanya, trusting in her to choose him. It is a tense moment, reminiscent of the trials of The Magic Flute, but love wins: she holds in her heart the phrase, “He walks on earth”, and suddenly recognises in his face alone an earthly quality. Singing their final love song to each other, they reaffirm their mutual devotion:

Listen, my friend,

I am in your heart,

I am always with you,

I love you, I love you,

When you think of me

you will hear the sound of my flute,

I love you, I love you.

Almost ten years on from my Indian adventure, I find that divinity is not an imagined paradise somewhere else, but it is all around us, be it in the madness of a bustling Indian city or underneath a dusty anthill, or sometimes revealed clearly in a musical performance, a marriage ceremony or a great work of art. I believe we can learn from the Indian musicians’ focus on the devotional aspect of practice, and from Sukanya’s devotion to unconditional love. When we have the ability to empty ourselves of ego and allow our devotional practice to come into its own, we hold the keys to discovering the divine.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Add comment