Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium, Whitechapel review - ten distinctive voices | reviews, news & interviews

Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium, Whitechapel review - ten distinctive voices

Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium, Whitechapel review - ten distinctive voices

Exhilarating proof that painting is alive and kicking

“From today, painting is dead.” These melodramatic words were uttered by French painter, Paul Delaroche on seeing a photograph for the first time. That was in 1840 and, since then, painting has been declared dead many times over, yet it refuses to give up the ghost.

Even now, when so many artists are choosing photography, film or video over paint on canvas, artists like Glenn Brown, Marlene Duma, Peter Doig and Jenny Saville continue to expand the possibilities of the archaic medium and prove there’s plenty of life in it.

The Whitechapel Gallery's new show Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium presents a new generation of artists who chose to paint and to make figurative work. Surely, this makes them doubly outdated ? Not a bit of it; the exhibition is bursting with vitality and there’s not a whiff of nostalgia in sight. A mood of edgy dysphoria permeates the work of these ten artists who hail from seven different countries. Most now live in Britain or the US, which may be why the social and political issues they address seem so pressing and so relevant.

At 58, German painter Daniel Richter is the oldest. Tarifa, 2001 (main picture) is based on a newspaper photograph of migrants attempting the hazardous crossing from North Africa to Spain in a small dinghy. They sit huddled together in an orange inflatable floating on a sea of inky darkness. As though picked out by thermal imaging cameras, their faces are carnivalesque masks painted in bright colours, which only heightens the tension. Their anxiety is palpable.

At 58, German painter Daniel Richter is the oldest. Tarifa, 2001 (main picture) is based on a newspaper photograph of migrants attempting the hazardous crossing from North Africa to Spain in a small dinghy. They sit huddled together in an orange inflatable floating on a sea of inky darkness. As though picked out by thermal imaging cameras, their faces are carnivalesque masks painted in bright colours, which only heightens the tension. Their anxiety is palpable.

In The Amazing Comeback of Dr Freud, 2004 Richter again uses psychedelic colours and exquisite paint handling to explore troubling subject matter. Rendered in liquid puddles of deep crimson, a cowboy stands ready to draw. He faces a green curtain of interlacing branches and, pinioned against them like a target, stands a man with hands up, naked save for a blond wig and red high heels. He turns to leer at us, as though excited by his crazy predicament.

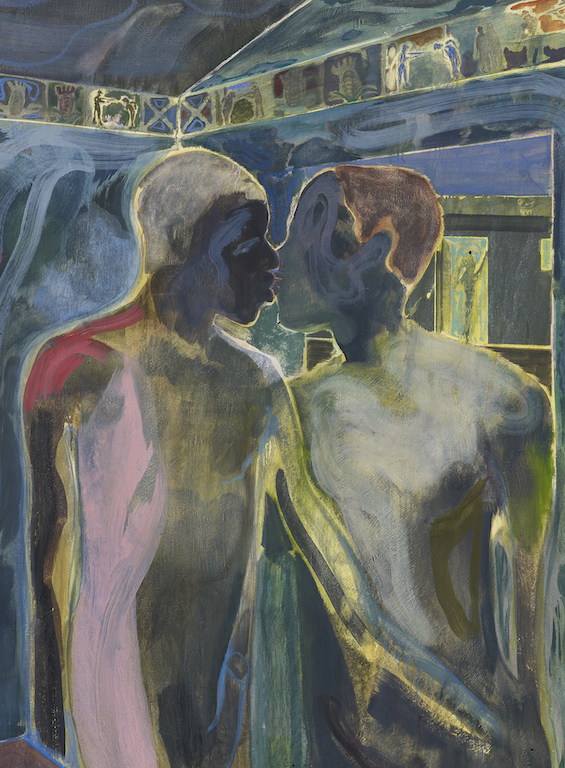

Michael Armitage similarly explores sexual politics in paintings that are as beautiful as they are disquieting. Born in Nairobi 36 years ago, he is one of the younger artists. In Kampala Suburb, 2014 (pictured above right) soft greys, lilacs and greens evoke a mood of gentle intimacy that bellies the hard-hitting topic. Two men kiss tenderly, but decorating the room is a frieze portraying firing squads – reminders of the death penalty awaiting gay couples under the Ugandan Anti-Homosexuality Act of 2014.

Women who step out of line also become targets. In Nairobi in 2015, a woman was assaulted by a bunch of men for wearing a miniskirt. In #mydressmychoice, 2015 Armitage based his reclining nude on Velasquez’s Rokeby Venus (1651), but the frieze of men’s feet bearing down on her emphasise her vulnerability; she has been stripped publicly. The hashtag in the title refers to the social media outcry prompted by the attack, while the woman’s iconic pose is a timely reminder that sexism is as old as the patriarchy.

Women who step out of line also become targets. In Nairobi in 2015, a woman was assaulted by a bunch of men for wearing a miniskirt. In #mydressmychoice, 2015 Armitage based his reclining nude on Velasquez’s Rokeby Venus (1651), but the frieze of men’s feet bearing down on her emphasise her vulnerability; she has been stripped publicly. The hashtag in the title refers to the social media outcry prompted by the attack, while the woman’s iconic pose is a timely reminder that sexism is as old as the patriarchy.

Updating or subverting art-historical themes is a common tactic. For instance, Russian artist Sanya Kantarovsky paints a mother and child, but instead of a serene madonna cloaked in blue, we get a blue nude bent double with apparent fatigue (pictured above). The red sores on her knees, elbow and chin suggest hardship or abuse; are her raised hands shackled or is she praying for release? The title, Letdown refers to breastfeeding and the rubbery infant lolling on her back like an incubus reaches for her nipple in hope. The embodiment of exploitation, she can expect no respite.

In Feeder, 2016 the tables are turned. A flamboyant pierrot sporting a pirate hat feeds an evil green liquid to a pathetic creature held by the scruff of the neck. In his cruel hands, the survival of this feeble ancient is far from assured.

Dana Schutz has clearly been looking at German Expressionists like Max Beckmann and Georg Baselitz. Imagine You and Me, 2018 (pictured right) features two puppet-like clowns crammed into a small boat with birds, fish and a rose for company. The theme and the searing colours are reminiscent of Beckmann’s Departure, 1935, but Schutz’s handling is so strident and declamatory that she bullies you into paying attention. Whereas Goya’s Saturn, 1823, devours his son, Schutz’s Man Eating His Own Chest, 2005, has bitten a hole in his own ribcage through which you can see the beach where this crazed individual is destroying himself.

Dana Schutz has clearly been looking at German Expressionists like Max Beckmann and Georg Baselitz. Imagine You and Me, 2018 (pictured right) features two puppet-like clowns crammed into a small boat with birds, fish and a rose for company. The theme and the searing colours are reminiscent of Beckmann’s Departure, 1935, but Schutz’s handling is so strident and declamatory that she bullies you into paying attention. Whereas Goya’s Saturn, 1823, devours his son, Schutz’s Man Eating His Own Chest, 2005, has bitten a hole in his own ribcage through which you can see the beach where this crazed individual is destroying himself.

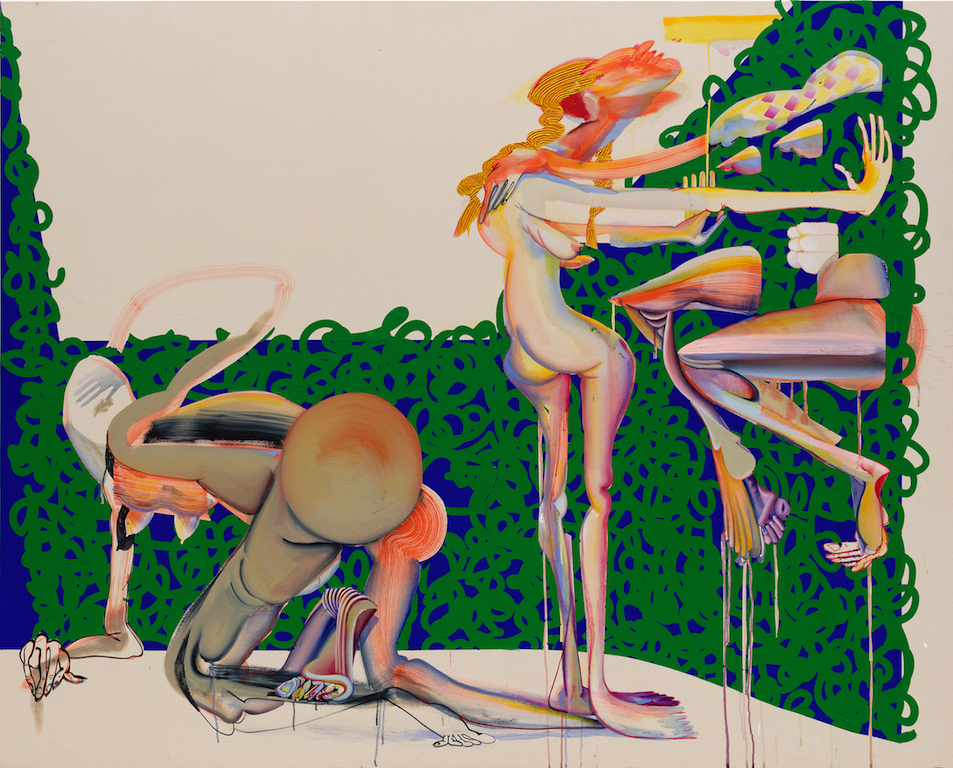

The anguish and impotence conveyed by Schutz’s characters also infects the work of Christina Quarles. In Casually Cruel, 2018 (pictured below) the influence of Hans Bellmer and Salvador Dali combine in the form of three bulbous yet skeletal nudes occupying a courtyard. Trapped in the green loops of the surrounding hedge, one is held prisoner by her companion. This unhappy drama radiates self-loathing as well as animosity. Had it been painted by a man, I would have accused him of misogyny, but coming from a woman it feels more like a cry of despair.  By contrast, Tschabalala Self’s figures radiate sassy self-assurance. Made from scraps of material collaged or sewn onto canvas alongside areas of blotted paint, her images put black men and women centre stage. Silhouetted against a bright turquoise ground, the hieratic figure of Lenox, 2019 wears a denim dress collaged over her brick-patterned legs and chest. Made from canvas impregnated with paint and stuck on, her hands and feet become comic appendages eager to gesticulate and dance.

By contrast, Tschabalala Self’s figures radiate sassy self-assurance. Made from scraps of material collaged or sewn onto canvas alongside areas of blotted paint, her images put black men and women centre stage. Silhouetted against a bright turquoise ground, the hieratic figure of Lenox, 2019 wears a denim dress collaged over her brick-patterned legs and chest. Made from canvas impregnated with paint and stuck on, her hands and feet become comic appendages eager to gesticulate and dance.

Whether anguished or celebratory, painting is clearly prancing into the new millennium with amazing gusto and expertise. These strong voices mean to be heard; in the hand of these artists, painting is not just alive, it is kicking up a stink.

- Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium at the Whitechapel Gallery until 10 May

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment