Nora: A Doll's House, Young Vic review - Ibsen diced, sliced and reinvented with poetic precision | reviews, news & interviews

Nora: A Doll's House, Young Vic review - Ibsen diced, sliced and reinvented with poetic precision

Nora: A Doll's House, Young Vic review - Ibsen diced, sliced and reinvented with poetic precision

Stef Smith brings exhilarating spirit to a familiar classic

Ibsen's Nora slammed the door on her infantilising marriage in 1879 but the sound of it has continued to reverberate down the years.

Translation can spell liberation. Where Victorian English might be distancing, a new version of a play originally written in another language immediately benefits from the immediacy of familiar speech. Stef Smith began as a poet and her enjoyment of language in different registers, with a hint at period changes, is one of the pleasures of this piece. Here there are three Noras at three stages of liberation: 1918 when (some) women earned the right to vote; 1968 just after the legalisation of abortion and when the contraceptive pill was coming into general use; and 2018 as the #MeToo movement gathered momentum.

Translation can spell liberation. Where Victorian English might be distancing, a new version of a play originally written in another language immediately benefits from the immediacy of familiar speech. Stef Smith began as a poet and her enjoyment of language in different registers, with a hint at period changes, is one of the pleasures of this piece. Here there are three Noras at three stages of liberation: 1918 when (some) women earned the right to vote; 1968 just after the legalisation of abortion and when the contraceptive pill was coming into general use; and 2018 as the #MeToo movement gathered momentum.

Smith has not so much adapted Ibsen as exploded the original while adding a pacey intensity. Some names are changed, but the bones of the story are here: Nora's apparently perfect marriage and family life are threatened by the impending revelation by a blackmailer of her fraudulent acquisition of money to aid her husband's recovery from a breakdown. Christine, an old friend of Nora's and a previous lover of the would-be blackmailer, an employee of Nora's husband, intervenes, but in the end all is revealed and Thomas (Ibsen's Torvald) shows himself to be weak and unworthy of his wife's love. She walks out on the marriage.

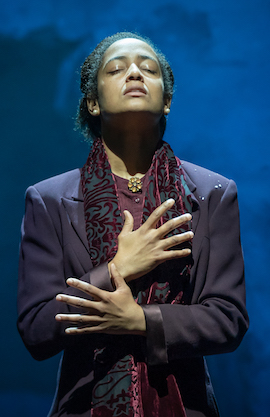

Smith's three Noras are sometimes interchangeable, sometimes very much of their time. They occasionally speak in chorus or use the third person to describe their/her predicament, but they are also differentiated, by both class and demeanour. Anna Russell-Martin is a tough, hard-talking contemporary Scot, Natalie Klamar is an Estuary Sixties woman hesitantly discovering new sexual possibilities, while Amaka Okafor (pictured right) has an elegant, middle-class dignity as the 1918 Nora. Each has a secret means of escape from the day-to-day: sugar for the earliest Nora; pills, "mother's little helpers", in the Sixties, and alcohol in 2018. Luke Norris, Thomas in every case, slips into altered speech and posture as necessary. All three Noras also play three Christines. The whole thing – a tense hour and 45 minutes – is beautifully controlled and choreographed in Elizabeth Freestone's sympathetic direction. Tom Piper's abstract set – three lit doorways with the suggestion of an icy river beyond – with audience on three sides of a thrust stage, and Michael John McCarthy's moody soundscape, often suggestive of heartbeats, complete Nora's world.

Smith's three Noras are sometimes interchangeable, sometimes very much of their time. They occasionally speak in chorus or use the third person to describe their/her predicament, but they are also differentiated, by both class and demeanour. Anna Russell-Martin is a tough, hard-talking contemporary Scot, Natalie Klamar is an Estuary Sixties woman hesitantly discovering new sexual possibilities, while Amaka Okafor (pictured right) has an elegant, middle-class dignity as the 1918 Nora. Each has a secret means of escape from the day-to-day: sugar for the earliest Nora; pills, "mother's little helpers", in the Sixties, and alcohol in 2018. Luke Norris, Thomas in every case, slips into altered speech and posture as necessary. All three Noras also play three Christines. The whole thing – a tense hour and 45 minutes – is beautifully controlled and choreographed in Elizabeth Freestone's sympathetic direction. Tom Piper's abstract set – three lit doorways with the suggestion of an icy river beyond – with audience on three sides of a thrust stage, and Michael John McCarthy's moody soundscape, often suggestive of heartbeats, complete Nora's world.

Although there is a distinct feminist call to arms here, there is also an acknowledgement that things have changed in 100 years. Women can vote, they can work, have loving relationships with each other without embarrassment and choose whether to have children, but without financial independence choice is still limited. And this is not restricted to women: Nathan (Ibsen's Krogstad: played by Mark Arends, pictured above left) is just as desperate to do the best for his family in pinched circumstances, just as prone to break society's rules to do so as Nora. Choice, the freedom to choose, is a theme that runs through the play. It is notable that Smith's Nora – in all her manifestations – seems unsure whether her children are a barrier to her self-realisation, that she wishes them gone because she lacks the confidence to be a good enough mother or she simply adores them. Or perhaps all three. Freedom is a desirable ambition, but achieving it is complicated. The play ends with a half-completed sentence on the idea.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

The Harder They Come, Stratford East review - still packs a punch, half a century on

Natey Jones and Madeline Charlemagne lead a perfectly realised adaptation of the seminal movie

The Harder They Come, Stratford East review - still packs a punch, half a century on

Natey Jones and Madeline Charlemagne lead a perfectly realised adaptation of the seminal movie

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

Add comment