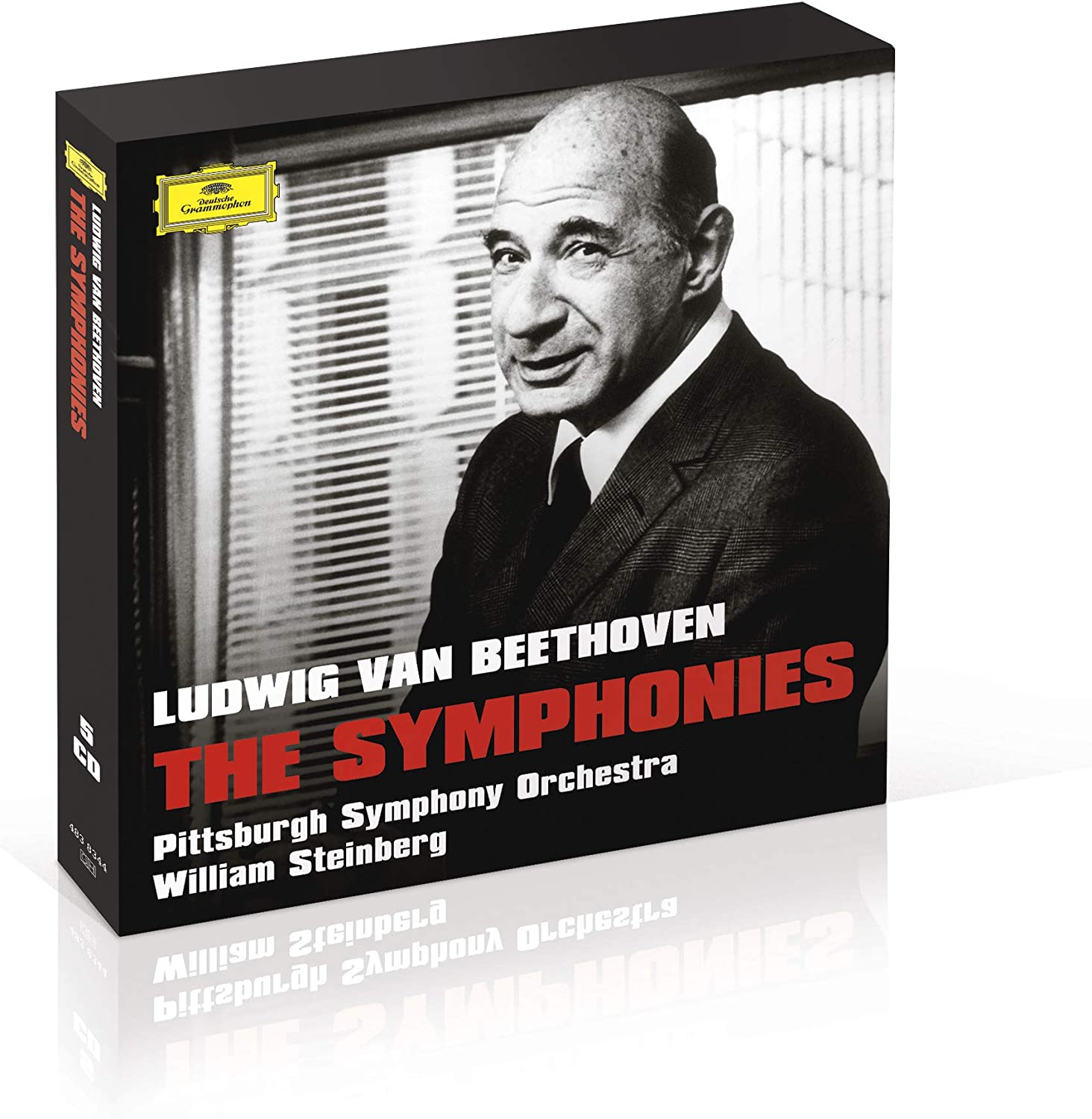

Beethoven: Symphonies 1-9 Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra/William Steinberg (DG)

Beethoven: Symphonies 1-9 Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra/William Steinberg (DG)

Cologne-born Hans Wilhem Steinberg was a youthful Music Director of the Frankfurt Opera in the early 1930s. He was relieved of his role, mid-rehearsal, in 1933, owing to his Jewish background. After a spell with the Palestine Symphony Orchestra he arrived in New York, initially as Toscanini’s assistant at NBC. A naturalised US citizen from 1944, he anglicised his name to William and secured the directorship of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra in 1952, remaining there until 1976. A few of Steinberg’s recordings have retained a foothold in the catalogue (his versions of Holst’s Planets and Hindemith’s Mathis der Maler are classics) but this remarkable Beethoven cycle has been out of circulation for a while. Originally taped between 1962 and 1966 and issued on the now defunct Command Classics label, it sounds marvellous. Engineer Bob Fine used expensive 35mm magnetic film, DG’s new remasterings highlighting the recordings' wide dynamic range and clear stereo separation. Only No. 9’s finale sounds a little more constricted, an original vinyl pressing standing in for a missing master tape. You won’t notice. This is the one Beethoven symphony I can struggle with, but Steinberg kept me interested. There’s a craggy magnificence to his reading, helped by his following Mahler’s lead in quadrupling the winds and adding a tuba. Good soloists and a full-throated chorus make the finale hit home.

These are exceptional performances. Steinberg invariably chooses apt tempi and secures flawless playing from a crack orchestra. There’s real joy in the cheerier moments, Symphony No. 2’s first movement among the best you’ll hear. Listen to the string articulation at the start of No. 4’s last movement, and note how neatly the same work’s final bars are wrapped up. No. 3’s funeral march broods, followed by a scherzo which really dances. There’s not a single misstep, which isn’t to imply that Steinberg is boring. The exultation he brings to the close of No. 5 is thrilling, and there’s an apocalyptic storm in No. 6. If you really need convincing, try Steinberg in the seismic closing pages of No. 7, horns, timps and swirling strings giving their all. This is one of the great Beethoven cycles. Buy it.

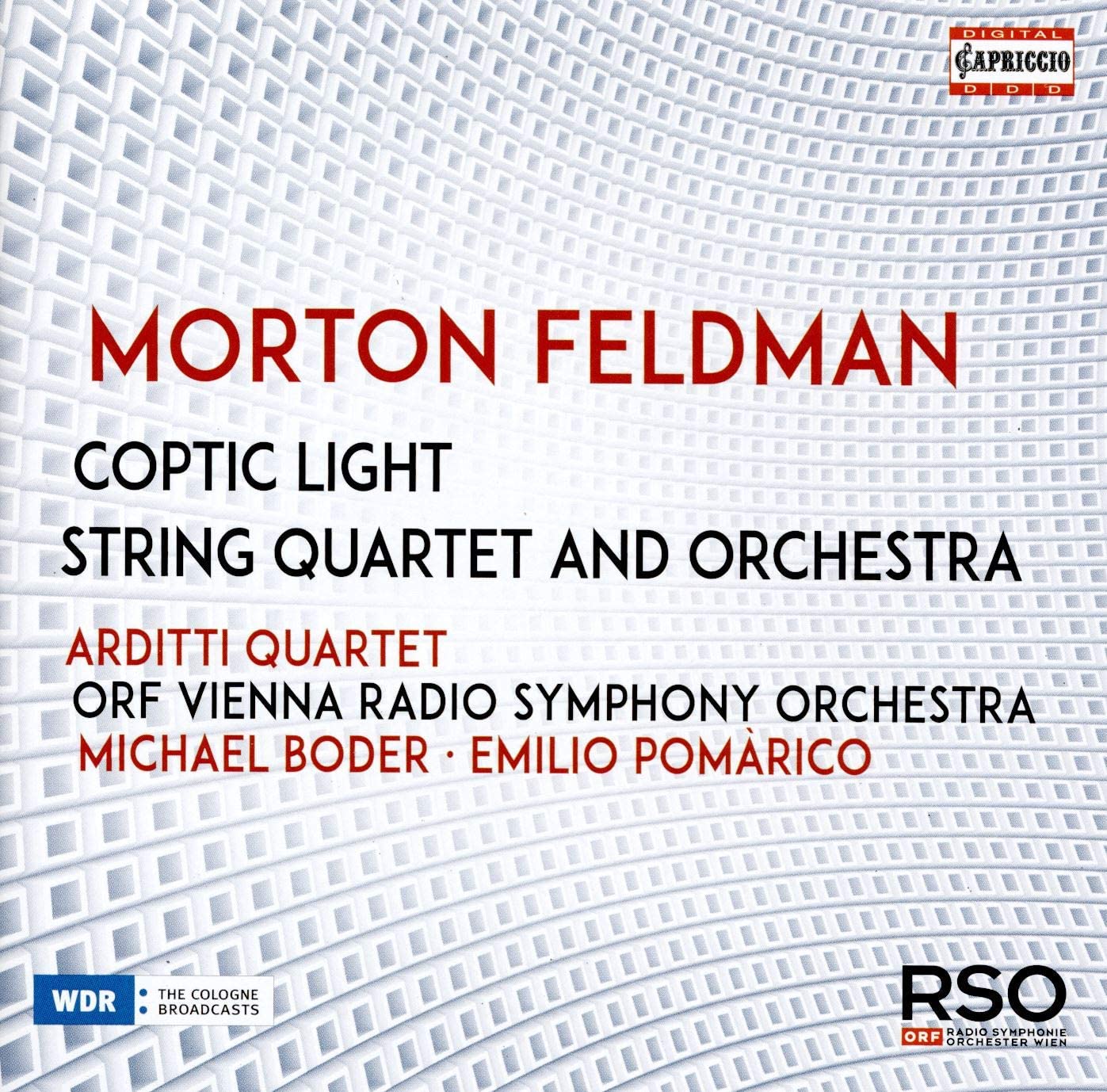

Morton Feldman: Coptic Light, String Quartet and Orchestra Arditti Quartet, ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra/Michael Boder, Emilio Pomàrico (Capriccio)

Morton Feldman: Coptic Light, String Quartet and Orchestra Arditti Quartet, ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra/Michael Boder, Emilio Pomàrico (Capriccio)

Morton Feldman spent many years combining composition with a job in the family textile firm. He became a professor at the University of New York in Buffalo in 1973, and it was Michael Tilson Thomas’s Buffalo Philharmonic which commissioned Feldman’s String Quartet and Orchestra in the same year. If you’re new to Feldman, start with this album. Hopefully you’ll soon be hooked, and en route to acquiring his five-hour String Quartet No. 2. String Quartet and Orchestra offers listeners 26 minutes of gradually evolving colours, the musical processes surely suggested by the patterns of the Middle Eastern rugs which Feldman so admired. A parade of soft chords, shifting textures and pregnant pauses, this glacially paced concerto grosso is gripping. The Arditti Quartet, here teamed with the ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra under Emilio Pomàrico, can tackle this stuff in their sleep but all concerned sound fully committed. The sole mystery is why this performance waited a decade before release.

Coptic Light dates from 1986. Feldman’s last completed work was explicitly inspired by Coptic textile art he’d admired in the Louvre, and how “these fragments of coloured cloth… conveyed an essential atmosphere of their civilisation.” A vast orchestra is deployed with incredible subtlety, Feldman’s attempt to “create an orchestral pedal, continually varying in nuance” resulting in an unbroken 28-minute span of music, without silences. It’s beautifully performed here, Michael Boder accentuating the warmth along with the strangeness. Both works are captured in clear, detailed sound.

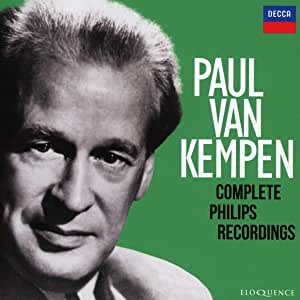

Paul van Kempen: Complete Philips Recordings (Decca Eloquence)

Paul van Kempen: Complete Philips Recordings (Decca Eloquence)

Paul van Kempen began his musical career as a violinist, joining the Concertgebouw in 1913. Relocating to Germany in search of opportunities to conduct, van Kempen became a German citizen in 1932, always hoping to return home to lead a Dutch orchestra. He finally took charge of the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic in 1949. A prolific recording artist, his obscurity is in part due to his decision to work in Dresden and Aachen during the war years. Though cleared of any misconduct, his reputation remained tarnished. A 1951 Verdi Requiem performance in Amsterdam was disrupted by stink bombs and uncooperative Concertgebouw musicians, while a Jewish harpist in the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic refused to be photographed with the conductor. Van Kempen was admired and respected, but unloved. Bernard Haitink attended one of his conducting courses and worked under him as a violinist, admiring his ability to make orchestras play well, despite the fact that “he sometimes gave musicians a really hard time… to be honest he did not have a very pleasant manner.” That the playing across the various ensembles featured here is so tight, so exciting is surely testament to the musicians’ professionalism as well as van Kempen’s technique. Try the 1951 Concertgebouw versions of Tchaikovsky’s last two symphonies, both wonderfully taut, the precision married to a winning rhythmic flexibility. No. 5’s first movement is exciting, and 6’s slow finale is very dark indeed. Versions of Beethoven 3, 7 and 8 with the Berlin Philharmonic have weight and drive. Van Kempen also gives us Reger’s imposing Hiller Variations, the Bachian final fugue never sounding stodgy.

The Netherlands Radio sessions are more eclectic. The rarity is Alexandre Tansman’s unwieldy 1950 oratorio Isaïe, le prophète, the choral writing well-served and tenor Cornelius Kalman shining in a difficult solo role. The rest is all orchestral and vocal operatic extracts, the soloists members of the Netherlands Opera. Van Kempen comes across as a thoughtful, sensitive accompanist, and it’s always fascinating to hear how vocal styles have changed over decades. Sessions with the Orchestre Lamoreux taped in 1955 reveal some attractive, distinctively French playing, with beautiful versions of Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream overture and Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings. And we get van Kempen’s last recording, an exciting Verdi Requiem recorded in Rome in April 1955 with Santa Cecilia forces. There’s months of fun to be had exploring this lot. Niek Nelissen’s notes are detailed, and good to see the original Philips LP covers reproduced on the card sleeves.

Add comment