Hough, Hallé, Elder, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester online review - brassy, bouncy optimism | reviews, news & interviews

Hough, Hallé, Elder, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester online review - brassy, bouncy optimism

Hough, Hallé, Elder, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester online review - brassy, bouncy optimism

World premiere of Huw Watkins’ Second Symphony in filmed performance

Sir Mark Elder is back with the Hallé for the latest (and penultimate) filmed concert in their “Winter Season” of 2020 and 2021, including the world premiere of Huw Watkins' Second Symphony. He introduces it from the Bridgewater Hall foyer, and mentions plans for a six-concert summer series with audiences present in the hall – well, let’s hope so.

There’s the usual “tuning up” brief clip of the busy streets of Manchester, and it’s straight into Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, with principal flute Amy Yule’s delightful solo, the harps of Marie Leenhardt and Eira Lynn Jones, and some luscious sounds from the strings led by Simon Blendis. Elder controls the dynamic levels beautifully, and the woodwind articulation is crisp and piquant.

The music continues with Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini: chosen not just because it’s a popular piece, but because it’s one where the Hallé Orchestra has the distinction of having given its British premiere, back in 1935. Sir Mark talks to the Hallé archivist, Eleanor Roberts, about the ambitions of the time, when Rachmaninov’s fee as soloist equalled more than the payments to the entire orchestra and was over double the conductor’s. (There’s nothing like star quality in hard times – the attendance was higher than that of practically every other Hallé concert in the 1930s).

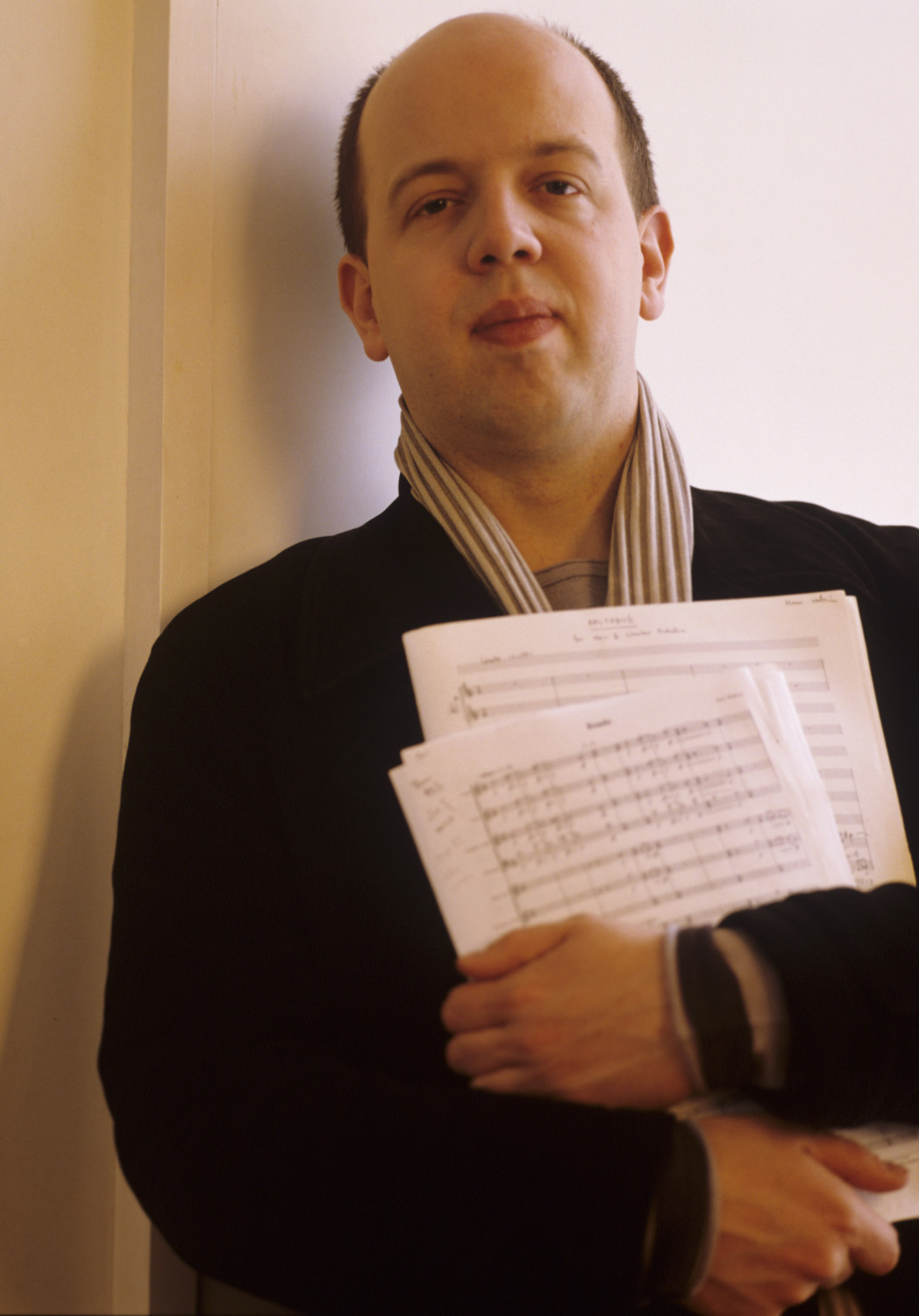

Our soloist this time is Stephen Hough (pictured left), who’s recorded all Rachmaninov’s concertos, and the filming by Maestro Broadcasting Limited (with sound by Steve Portnoi) captures his star quality, too, zooming frequently in on his face, his piano and his fingers. The partnership with Elder seems made in heaven, the music rhythmically alive, light-hearted until Variation Seven, changing instantly to wistfulness and questioning, and then grimmer as the “Dies Irae” quotations obtrude. Variation 12 is beautifully poised, and conductor and soloist work up a tantalising approach to the big tune of Variation 18 (which Hough plays ecstatically), before the charge to the end.

Our soloist this time is Stephen Hough (pictured left), who’s recorded all Rachmaninov’s concertos, and the filming by Maestro Broadcasting Limited (with sound by Steve Portnoi) captures his star quality, too, zooming frequently in on his face, his piano and his fingers. The partnership with Elder seems made in heaven, the music rhythmically alive, light-hearted until Variation Seven, changing instantly to wistfulness and questioning, and then grimmer as the “Dies Irae” quotations obtrude. Variation 12 is beautifully poised, and conductor and soloist work up a tantalising approach to the big tune of Variation 18 (which Hough plays ecstatically), before the charge to the end.

The major item on the order paper, however, is the premiere of Huw Watkins’ Symphony No. 2. The Hallé brought his First Symphony to birth in Manchester in April 2017, and this was if anything an even more auspicious occasion. First the orchestra’s principal percussion, David Hext, and principal flute, Amy Yule, discuss the challenges of playing new music, and then we are whisked away to the conductor’s room for Elder to discuss the symphony with its composer. Watkins reveals that he began work on it just before last year’s first lockdown, and its creation “really spanned the whole year for me”. He also calls it “a very welcome escape from the depressing things going on around us”, while Sir Mark comments on its “incredibly optimistic” ending.

So it’s very much a piece of our time, and no doubt it could hardly be anything else. It has a long central slow movement which seems quite elegiac, with a sense of something lost – and a meditative quality that means perhaps Watkins (pictured right by Hanya Chlala) has rejuvenated the English symphonic pastoral tradition with this one. But that’s not all. His music here is tonal and often lyrical, but it has many rhythmic subtleties and clangorous climaxes. Its opening movement begins in a mellow mood, with a brief, simple motif played canonically in the woodwind, and grows to a brassy highpoint; there’s a kind of second start, with similar opening material differently developed and accelerating to another peak. After it comes a lovely theme on oboe and then flute and also strings, almost Copland-esque in its wide intervals, with an acceleration and crescendo before a recall of the opening, now fragmentary and inconclusive.

So it’s very much a piece of our time, and no doubt it could hardly be anything else. It has a long central slow movement which seems quite elegiac, with a sense of something lost – and a meditative quality that means perhaps Watkins (pictured right by Hanya Chlala) has rejuvenated the English symphonic pastoral tradition with this one. But that’s not all. His music here is tonal and often lyrical, but it has many rhythmic subtleties and clangorous climaxes. Its opening movement begins in a mellow mood, with a brief, simple motif played canonically in the woodwind, and grows to a brassy highpoint; there’s a kind of second start, with similar opening material differently developed and accelerating to another peak. After it comes a lovely theme on oboe and then flute and also strings, almost Copland-esque in its wide intervals, with an acceleration and crescendo before a recall of the opening, now fragmentary and inconclusive.

The Lento opens with a foil of muted strings and soft wind and brass to a lovely solo melody for flute (and then oboe), in short but eloquent phrases, and its second theme is decorated by the wind in flowery combination: there’s an accelerating crescendo, and then another, but the second is brief, and cut short by a return to the opening melody. The third and last movement gives us a lot to take in, Sibelian in the sense that it seems like a development seeking a theme – several times over. But whereas the ending of Watkins’ first symphony was like the flick of a switch in mid-flow, this, though it finally stops quite abruptly, has by then manifestly arrived at its destination. Yes, it is incredibly optimistic.

Perhaps, one day, people will look back on the second symphony as capturing the spirit of Britain through the course of its Covid experience. They may even find an equivalence between the brassy, bouncy optimism of its final pages and the upbeat approach of Boris Johnson. Well, let’s hope so.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Add comment