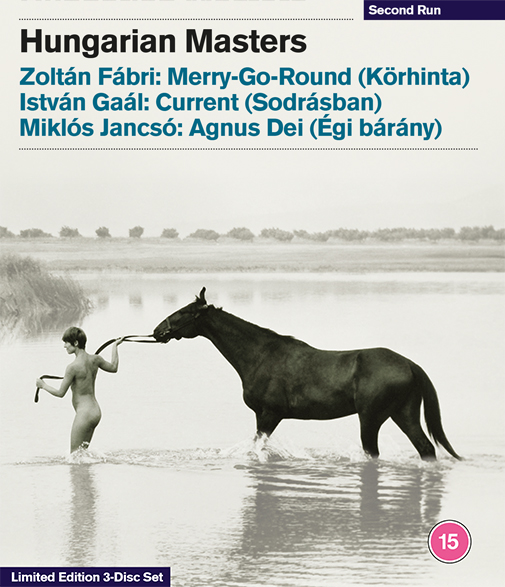

Three films, each restored to glorious 4K, make up Second Run’s Hungarian Masters set. Billed as “essential works by three of Hungarian cinema’s most renowned filmmakers”, each film earns that praise in its own way.

Zoltán Fábri’s Merry-Go-Round is the first, released amid the final months of Mátyás Rákosi’s de-facto leadership, a period defined by intense industrialisation, militarisation and collectivization. Fábri and his contemporaries witnessed a severe decline in living standards, purges, and the deportation of more than half a million Hungarians to the Soviet Union, where an estimated 200,000 died in forced labour camps.

Merry-Go-Round is at once a product of the Rákosi era, and perhaps more subtly, a symptom of the shifting national sentiment towards it. An adaption of the novel In the Well (Kútban) by Imre Sarkadi, the film opens at a country fete somewhere in the Hungarian Pustza, roughly in the vicinity of Debrecen. There, a travelling circus forges a path between the thronging crowd, holding above them a banner that reads “Le a burszda formalizmussal!” (“Down with Bourgeois formalism!”), with the circus name beneath it. Among the crowd is a farmer’s daughter, Mari. Spotting the banner, she turns to her father in search of an explanation, to which he replies with disdain: “somebody’s come up with something again”. It is a light-hearted opening, replete with symbolism: Mari’s father has just decided to withdraw from the local farming co-operative. In the austerity of his comment, he establishes himself from the off as the stand-in for a weak and joyless individualism.

Despite its synopsis, however, Merry-Go-Round is a more vibrant offering than the socialist realism that preceded it. Where directors might once have spied a vacuum for political slogans and insipid didacticism, Fábri is firmly committed to the human, couching his film within the sure-fire confines of a classic trope, of star-cross’d lovers. Mari is the film’s Juliet, its Romeo the polite and dignified Máté, a servant of that same co-operative. Merry-Go-Round remains fixed on this pair, and Mari in particular, levied with the burden of choice: family loyalty, or love?

Despite its synopsis, however, Merry-Go-Round is a more vibrant offering than the socialist realism that preceded it. Where directors might once have spied a vacuum for political slogans and insipid didacticism, Fábri is firmly committed to the human, couching his film within the sure-fire confines of a classic trope, of star-cross’d lovers. Mari is the film’s Juliet, its Romeo the polite and dignified Máté, a servant of that same co-operative. Merry-Go-Round remains fixed on this pair, and Mari in particular, levied with the burden of choice: family loyalty, or love?

Two decades later, Hungary’s capricious political landscape was the subject of another film, this time directed by Miklós Jancsó. Agnus Dei (Égi bárány, 1971) is the youngest inclusion in Hungarian Masters and its most historical, winding the clock back to 1919, when out of the dissolved Austro-Hungarian Empire arose the Hungarian Soviet Republic. Agnus Dei is an allegorical dramatisation of the 133-day duration of that Republic, in which confusion and bloodshed reign as a group of villagers are successively set upon by conquering forces. Echoing the sublime steppe which furnishes Jancsó with his stage, the tyrants prove indifferent to the lives of the villagers, whose slaughter – within the film, but similarly in the conscience of the viewer – is swiftly rendered routine.

Watching Agnus Dei, it is possible to discern a communist here, or an anti-communist there. Yet, the individual scenes of which the film is comprised are less significant than their weaving, through Jancsó’s lingering shots, into a form of visual tapestry. Writing in “The Bloodless Lambs”, the accompanying essay to the Second Run disc, critic Tony Rayns notes how this “roving camera” serves as a mirror to the chaos and instability of the time, and is a technique that Jancsó’s would carry forward to his later films: Red Palsm (Még kér a nép, 1971) and Electra, My Love (Szerelmem, Elektra, 1974). The last of these, adapted from Euripides, shares with Agnus Dei more than the looping, circular path of Jancsó’s lens, and the illusion of space it creates, however. More so, Electra, My Love depicts a near-identical subjection of everyday people to the whim of higher political and theological forces. Thus, Jancsó’s oeuvre underlines a macabre proximity between the events of inter-war Hungary, and the prevailing concerns of Attic tragedy. (Pictured below, Mari Törócsik and Imre Soós in Merry-Go-Round) István Gaál is the least celebrated of Hungarian Masters’ trio of directors, but Current (Sodrásban, 1964) is the quickest of all to dispel any notion of gratuitous or unwarranted selection. A foil to his compatriots, Gaál draws away from the political sphere into an existential rumination upon the nature and quality of existence, depicting the psychological impact upon a group of teenage friends of the sudden loss of one of their number. Current is the most visually impressive film of the set; shot in luscious monochrome, the site – of the film, and of the death – is the river Tisza. Its shadow hangs over Current as a whole, haunting the afterlives of Gaál’s remaining characters as they endure a fruitless scramble for closure and comprehension, the film charting their transition from a tightly knit unit into a fragmented assembly of individuals. One scene in particular brings this quietly, but clearly, into view: trudging home from their loss, each of the friends peels off to make their own way home, sliding through a gate, or wheeling off on their bike – to leave just one figure standing alone.

István Gaál is the least celebrated of Hungarian Masters’ trio of directors, but Current (Sodrásban, 1964) is the quickest of all to dispel any notion of gratuitous or unwarranted selection. A foil to his compatriots, Gaál draws away from the political sphere into an existential rumination upon the nature and quality of existence, depicting the psychological impact upon a group of teenage friends of the sudden loss of one of their number. Current is the most visually impressive film of the set; shot in luscious monochrome, the site – of the film, and of the death – is the river Tisza. Its shadow hangs over Current as a whole, haunting the afterlives of Gaál’s remaining characters as they endure a fruitless scramble for closure and comprehension, the film charting their transition from a tightly knit unit into a fragmented assembly of individuals. One scene in particular brings this quietly, but clearly, into view: trudging home from their loss, each of the friends peels off to make their own way home, sliding through a gate, or wheeling off on their bike – to leave just one figure standing alone.

Ultimately, in Fabri’s realism, Janco’s furious politicism, and the beauty of Gaal’s aesthetic, Hungarian Masters showcases the issues and themes – some stable, others shifting – that defined mid-century Hungary. The set is complete with a series of informative special features, including interviews with Hungarian filmmaker István Szabó on the influence and legacy of Zoltán Fábri, and with Miklós Jancsó, discussing his earlier film The Red and the White (Csillagosok, katonák, 1967), along with Tisza - Autumn Sketches (Tisza - Őszi vázlatok, 1962), István Gaál’s short film observing autumn descent along the Tisza. And to round things off are further excellent essays from Hungarian cinema specialists John Cunningham and Peter Hames, without whose unbridled insights on local culture, and attentiveness to the formal accomplishments on display, the experience of this marvellous collection would be incomplete.

Add comment