Music Reissues Weekly: Shake That Thing - The Blues in Britain 1963-1973 | reviews, news & interviews

Music Reissues Weekly: Shake That Thing - The Blues in Britain 1963-1973

Music Reissues Weekly: Shake That Thing - The Blues in Britain 1963-1973

Box-set compendium of US-inspired Brits lacks inquisitiveness

In September 1955, the grandly named London Skiffle Centre set up for business each Thursday in a room above the Round House pub in Soho’s Wardour Street. A prime mover in the venture was blues acolyte Cyril Davies. Two months after the opening, Lonnie Donegan’s “Rock Island Line” was issued as a single. It was previously out as a track on a 1953 Chris Barber album. Despite the wonky timeline, the skiffle boom was on.

Davies – now in partnership with fellow blues enthusiast Alexis Korner – grew increasingly dissatisfied with skiffle and in March 1957 the duo renamed The London Skiffle Centre as The Blues and Barrelhouse Club. London’s blues enthusiasts had their own hub, contrasting with Ewan MacColl’s similarly named but folk-oriented – and sporadic – Ballads & Blues club. By this point, alongside skiffle, a British rock ’n’ roll had also emerged in Soho and the Skiffle Centre rebranding put a distance between the blues-niks and the Elvis wannabes as well as the skifflers.

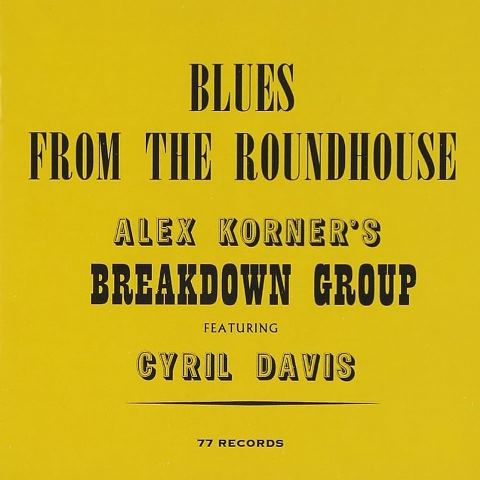

A further line was drawn in November 1957 when the live 10-inch album Blues From the Roundhouse was issued. Credited to Alex Korner's Breakdown Group Featuring Cyril Davis (sic), it had been recorded on 1 February 1957. On vinyl, this is when British blues first asserted itself – albeit on a record of which only 99 copies were pressed. In 1959, it was followed by the Blues From the Roundhouse Vol. 2 EP

A further line was drawn in November 1957 when the live 10-inch album Blues From the Roundhouse was issued. Credited to Alex Korner's Breakdown Group Featuring Cyril Davis (sic), it had been recorded on 1 February 1957. On vinyl, this is when British blues first asserted itself – albeit on a record of which only 99 copies were pressed. In 1959, it was followed by the Blues From the Roundhouse Vol. 2 EP

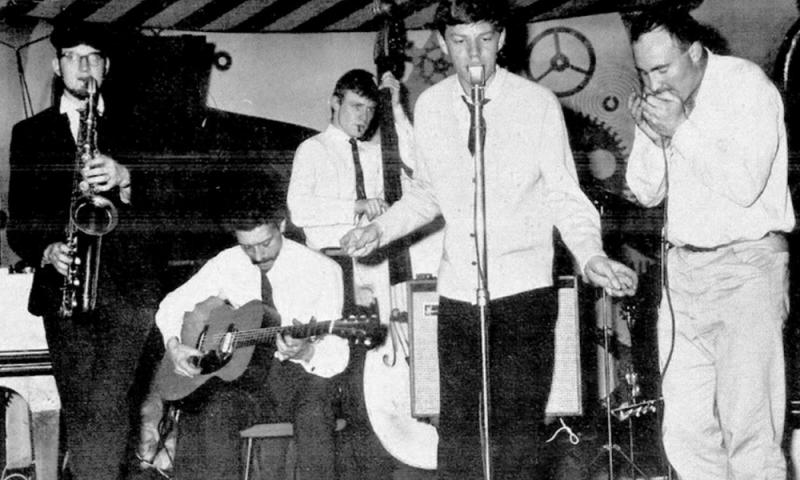

There was an audience for blues. The first half of the Fifties saw Big Bill Broonzy, Lonnie Johnson and Josh White play the UK. The first electric blues player to hit Britain was Muddy Waters. His October 1958 show at St Pancras Town Hall was, according to Melody Maker, “remarkable…tough, unpolite…often very loud” with “violent, explosive guitar accompaniment.” During this visit, Waters also played the Round House.

It took a while, but Davies and Korner went on to form Blues Incorporated, who played their first live show in March 1962. Guests with the band formed The Rolling Stones, Manfred Mann and more. But some of the newer wave of blues fans did not seem to be purists. Brian Jones, of the recently formed Rollin’ Stones (as they were then) wrote to Jazz News in late 1962 and mentioned “rhythm-and-blues.” This is what his band played.

What of the purists? Those wedded to blues, and blues alone. Not everyone could be an Eric Clapton, who left The Yardbirds in February 1965 as he didn’t like the pop direction embraced on their new single “For Your Love.” Such purism wasn’t necessarily rife though. Players like Davy Graham, Bert Jansch, John Renbourn included blues material in their repertoires – it was an aspect of what they did.

Following his anti-pop flouncing off, Clapton joined John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and then formed Cream with Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce – both of whom had passed through Blues Incorporated. As well as the initially blues-focused Cream, The Bluesbreakers were also in the roots of Fleetwood Mac, who first surfaced on record in November 1967 with a single on Blue Horizon, a blues-dedicated label set up by producer Mike Vernon. British blues had developed a family tree stretching back more than a decade.

Following his anti-pop flouncing off, Clapton joined John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and then formed Cream with Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce – both of whom had passed through Blues Incorporated. As well as the initially blues-focused Cream, The Bluesbreakers were also in the roots of Fleetwood Mac, who first surfaced on record in November 1967 with a single on Blue Horizon, a blues-dedicated label set up by producer Mike Vernon. British blues had developed a family tree stretching back more than a decade.

Around this point, 1967/1968, what became known as the “British Blues Boom” was getting going – as well as Fleetwood Mac, bands like Chicken Shack, Savoy Brown and Ten Years After were offering an alternative to hippie stuff, psychedelia and records which drew from advances in recording techniques and studio technology.

There is always a tension between the commercial and music with a niche appeal – it was thus in 1957 when The London Skiffle Centre became The Blues and Barrelhouse Club. And when Clapton left The Yardbirds in 1965. Also, when Cream bowed to the inevitable to make singles fitting the pop bag. Nonetheless, with blues there were enough aficionados to propel it into, or situate it adjacent to, the mainstream. What went on between the setting-up of The Blues and Barrelhouse Club in 1957, the formation of Cream in 1966 and then Fleetwood Mac in 1967 demonstrated that British blues was embedded; that there was an alternative to pursuing the trends of the day, to follow a less-marketable path.

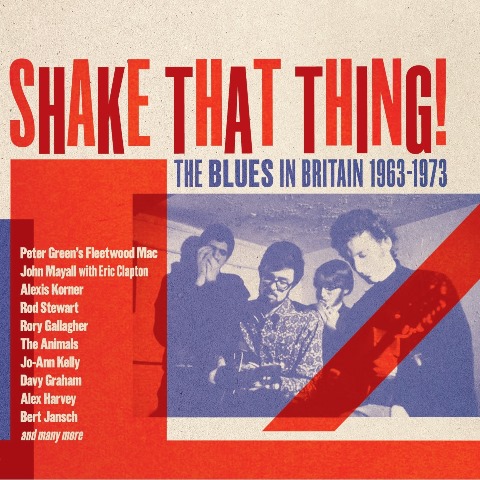

Shake That Thing - The Blues in Britain 1963-1973 is a 73-track clamshell box set with a booklet picking up the story with what had become Cyril Davies and His Rhythm and Blues All Stars and their April 1963 debut single “Country Line Special.” To stress its credibility, it was issued on Pye International, an imprint usually dedicated to material licensed from America instead of home-grown music, rather than parent-label Pye, the home of pop hits. It’s a wild record.

Shake That Thing - The Blues in Britain 1963-1973 is a 73-track clamshell box set with a booklet picking up the story with what had become Cyril Davies and His Rhythm and Blues All Stars and their April 1963 debut single “Country Line Special.” To stress its credibility, it was issued on Pye International, an imprint usually dedicated to material licensed from America instead of home-grown music, rather than parent-label Pye, the home of pop hits. It’s a wild record.

After this, the set's chronologically sequenced tracklist roams through Long John Baldry & The Hoochie Coochie Men, Rod Stewart’s “Good Morning Little School Girl,” Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated and solo acts like Davy Graham, John Renbourn and Beverley Martyn. The Animals are here but The Yardbirds are not. Curious. Ten Years After, with the October 1967 album track “Don’t Want you Woman” are Track 12 on Disc One. Next, Track 13, Disc One is from January 1968 (Ian A. Anderson’s “Cottonfield Blues”). The set is heavily weighted towards 1968 to 1973.

While the almost-four-hour Shake That Thing - The Blues in Britain 1963-1973 is an engaging listen, covers all stylistic bases, doesn’t overegg the well-known names and includes wild cards like the Incredible String Band, Pentangle and Trader Horne, who aren't usually thought of in a blues context, what’s missing is a clear sense of how the blues in Britain got to the period it really seems interested in: 1968 and later. And, also, why these British bands and players favoured blues is an unasked question. Themes another box set could grapple with?

- Next week: Back in the HCA - British art-school curio from 1972

- More reissue reviews on theartsdesk

- Kieron Tyler’s website

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Trio Da Kali, Milton Court review - Mali masters make the ancient new

Three supreme musicians from Bamako in transcendent mood

Trio Da Kali, Milton Court review - Mali masters make the ancient new

Three supreme musicians from Bamako in transcendent mood

Hollie Cook's 'Shy Girl' isn't heavyweight but has a summery reggae lilt

Tropical-tinted downtempo pop that's likeable if uneventful

Hollie Cook's 'Shy Girl' isn't heavyweight but has a summery reggae lilt

Tropical-tinted downtempo pop that's likeable if uneventful

Add comment