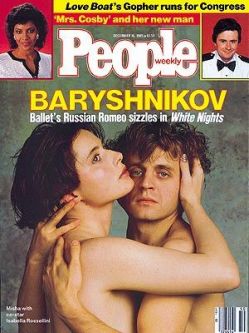

On Tuesday Mikhail Baryshnikov, just turned 62, will dance again, an evergreen superstar as well as philanthropist. The occasion will be the opening of the Jerome Robbins Theater, his latest project in his Baryshnikov Arts Center in New York. In this second collection of conversations with him - read part 1 here - edited from interview transcripts from 1993, 1996, 1999 and 2004, Baryshnikov talks about his devotion to George Balanchine, global celebrity with ABT and beyond, and the voyage he took into modern dance, using his fame and fortune (and TV's Sex and the City) to give back as much as he has received from his adopted country.

With Balanchine

ISMENE BROWN: I was moved by the foreword you wrote for Robert Greskovic's book Ballet 101: "When I first started going to the ballet, the thing that drew me back to it was not just the beauty of the performances, but the fact that that beauty seemed personal to me..." I wondered if classical ballet still feels part of your inner makeup.

MIKHAIL BARYSHNIKOV: It’s part of my psyche. It’s funny, I’ve been round dance companies for 10 or 12 years since I left ABT and I think my true home is New York City Ballet - where I feel most comfortable. When I go to see them perform, or take class there, it’s actually my home, although I spent not even two years with them a long time ago. Somehow the work there was the most meaningful, being next to Robbins and to George. It was the most challenging work - probably sometimes not personally successful from the critical point of view, and from the audience. And a lot of people misinterpreted that, that I was frustrated, that I didn’t like the way I was treated, dah-de-dah. It was nonsense. That was the most exciting time of my career. Somehow I grew up. I learned by seeing them work, I learned to try to understand their philosophy about the ethics of the theatre, and the relationship of the dancer and choreographer.

And not too much politics there then.

No. That company is not like any other company. It’s totally authoritarian, from one point of view, the way of the creator or creators. And that makes it kind of stable, that the dancers feel totally at home in, totally devoted. Stable - as in being stable, and also in horses’ stable! [laughs]. Balanchine used to say, “These are all my beautiful horses!”

But he also used to say dancers should do, not think.

Ach, no [indulgently]. He admired people, wanted them to have taste, to know music. It was more his aesthetics as choreographer, that he hated “acting” on stage, exaggerated mannerisms. He wanted the essence of his movement, and that’s why [shrug], “Shut up and dance, trust my dance and you will be beautiful.”

Was the fact that he was Russian important to you in feeling at home there?

Oh, I was fascinated by him as a human being. His authority and knowledge and genius. Although I knew that he was an old man already, and he said to me from the very beginning, “I am an old man, I may not able to make a new piece for you, but I will revive Harlequinade and Prodigal Son, and we will try our best.” He was happy that I asked him if I could join the company and we had a wonderful tête-à-tête relationship. He was a lonely man. He used to invite me for dinner just to go somewhere and speak Russian. That was a lot of fun.

You must both have dreamed of a very different Russia from that which you left.

Well, of course he was a monarchist. Well, of course. All his old heroes, Tchaikovsky, Stravinsky, they came out of the old monarchist Russia where he was a child. He left Russia immediately after the revolution, and that’s why he adored all those people. Somehow imperial Russia for him was the true inspiration and memory.

But the thing that was striking about American dance as Balanchine evolved it was that he took the stories out of ballet. You were writing about the value of those stories in your piece for Greskovic - so what takes the place of the stories?

Look at that book of him with Volkov on Tchaikovsky. That’s everything about stories. He knew literature very well, he knew Dostoevsky quite thoroughly, for him it was, you know, a certain knowledge at a certain time. I remember we were somewhere, I think in Paris, and John Taras said, “Mr B, why don’t we go to the Louvre?” And he said, “Dear, I was there in 1931, or something.” He didn’t have to go to the Louvre any more! [laughs] He knew Petipa ballets, he knew music, he wasn’t that curious about things going on around him. He knew what he wanted to do.

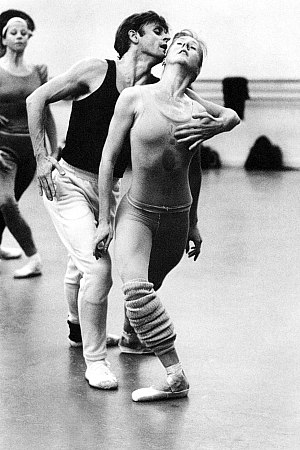

And you? Did you find stories interesting to dance? (Left: Baryshnikov in Balanchine's Apollo)

And you? Did you find stories interesting to dance? (Left: Baryshnikov in Balanchine's Apollo)

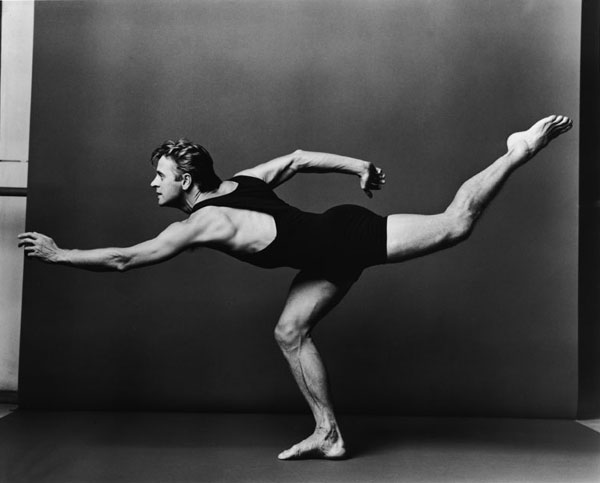

I am interested in the conceptual, but not in “acting” dance. I like contemporary work that reflects an idea which maybe at a human level is more complex and subtle than just beautiful dancing. I like the emotions behind it. I don’t necessarily want to show it on my face and milk it. But I am interested in the emotions under the skin that the dancer can project. Men have a bit of a hesitancy... well, they sometimes feel that in order to be romantic, they need to be "acting" a dreamer on stage, but you have to be simply honest, you cannot act it out. And that is the most difficult thing for any young dancer, because they are so preoccupied with the technical demands, the costume, the makeup, etc, that they forget to be themselves. And young men have a tendency to be more reserved about releasing themselves internally and being more transparent to the audience.

You see them approaching it from the athletic point of view.

Of course, because the young body is such a tuned instrument, it’s like young horses. They want to run. And athleticism sometimes... It can be fabulous, but it can blank you off.

Yes. What about you? You were so athletic when young. Where did you find, or who taught you about the dreaming side?

Well, I used to overdance a lot. In the mid-Eighties, say. I have great difficulty now in remembering how I worked in Russia where memories are muddy and dim, but I was working very hard in the mid-Eighties, when I was maybe over 30. I find I used to overdance everything, try to overpower myself in a way. Try to prove that my next performance would be cleaner, better and all that. I had a tendency to forget about the real essence of the dance, and how to do it with the minimum of effort, make it much more meaningful.

What showed you that something was missing?

I think I learned a lot from Balanchine and Robbins and from seeing some modern work, Cunningham, Graham. That there’s nothing wrong with the person being quiet on stage. The dynamics of a movement: it’s not just “what I know”. And I was trying to understand this better, and trust in those more static and quiet movements.

Balanchine became a sort of father figure to you?

I wouldn't say father figure, but we enjoyed each other's company. Sometimes we'd just stroll along - he lived not far away - sometimes after rehearsal I'd walk with him and have dinner, a Russian tearoom or an italian place, he liked good wine and a little vodka. Nice chat. Rarely dance, mostly about his childhood memories. About memories of theatre school and St Petersburg. Youth, pleasures to life, people in the past. But he was never a sentimental person. He’d say, “That was nice”, once, then that’s it.

Were you nervous coming to work with him, coming from the Kirov and ABT?

I knew people would always pick on me that I was not the right dancer there. I just went to be with this man, I didn't care where it took me as a dancer. I knew it would be endless different opinions from people, critics, audiences, dancers. I'd been before to see City Ballet, because some of my friends were there and you wanted to see the new pieces by Mr B and Robbins. I'd always wonder, can I do that? And then when I joined, it was snap, snap, snap, work after work. At that time, the end of the '70s, people were so possessive about everything - who was dancing this? Suzanne, or Allegra, or how dare he cast this person? This frenzy. He'd say, it's just dance, relax everybody, come on! [Laughs & shrugs.]

I'd worked already with Robbins - I felt comfortable with him, Robbins was instrumental about me coming. And Lincoln was very amusing - I had a great time with him, his tongue was so sharp, he was so observant and interesting. I just had a ball, and how my work was received I didn't really care seriously. Because I knew, somehow, that it was not for ever. I was there. It was a pleasure. It was an extra.

Who did you partner mostly?

Patty McBride, I danced with Heather Watts a bit, with Allegra a bit, with Kay Mazzo.

Why did you stay such a short time?

Because I was invited to take Ballet Theater. I talked to Balanchine a few times, and he didn't really try to stop me. He said, “It’s kind of upsetting, and I wish we could do a few more things, but at the same time I am a bit too old to do a lot of new pieces. If it comes it comes, but you cannot schedule those things. I understand it's not fun to always go to someone else's shoes in someone else’s role.” Actually Jerry did more new pieces for me at City Ballet. I would have stayed longer, probably, if I hadn't been approached by Ballet Theater.

So it was a tough decision.

It was.

Balanchine reminded us that art is a pleasurable luxury, and let's not make dogmas out of it, let's not point fingers, and try to decode the formulas

How do you think of Balanchine now? If you were directing the centenary celebration, how would you be focusing?

[Pause.] Well, I think, he reminded us of the endless opportunity for creativity. Without knowing, he stepped a century ahead of everybody. I remember when he was in Russia in 1962, and they were showing Serenade, and one reporter said to him, “Oh, Mr B, I cannot imagine Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for strings now any other way.” And he said, “You're wrong, tomorrow I can choreograph it in a completely different way. Maybe it would not be as good as this, but not less interesting." You know, this attitude that everything in art is really illusion, and that it's not dogma. He was very not dictatorial in his attitude to his work. It could be like this that day, and then change; what's important is the overall vision.

I remember something, when he was really furious - he changed costumes in Divertimento no 15 or something, a few changes, somebody was missing, and Arlene [Croce, the ballet critic] wrote this big thing in the New Yorker about he changed the psychological thing about Divertimento, and he was laughing about it in a class he was teaching. He was reading it out to the company and making fun of her, saying this is nothing to do with what I do, people could like this for this reason or that, let's make it interesting and fun, and not take each other too seriously.

And that's what I really like - that he reminded us that art is a pleasurable luxury, and let's not make dogmas out of it, let's not point fingers, and try to decode the formulas. Jerry Robbins was the complete opposite because he was so detailed about everything. But of course the man was a true genius, creating in a sort of Mozartian way.

You also knew Ashton - it was his centenary too with Balanchine.

Ashton's not a lesser choreographer than Balanchine. Ashton's a warmer choreographer - his skin is warmer, warmer as a person. I miss him. When he made Rhapsody I wanted to dance the Western way but Ashton wanted me to be big and Russian. He was such good fun, we had late-night times, cigarettes, vodka, he was good company. London isn’t the same for me without him. He’s an English choreographer of Russian school, he learned everything from Bronislava Nijinska. And Bronislava was one of the persons that after Petipa Balanchine actually admired, secretly. I talked with him about it. He was not altogether agreed about Svadebka (Les Noces). But he thought she was one of the most interesting choreographers, of that time, the first big neo-classical choreographer was her - I mean, Les Biches, ah! And in a way Ashton and Balanchine are choreographers of the same school.

Of course Ashton created fewer ballets - he was part of the, you know, imperial structure of the theatre, kind of, while Balanchine was a free artist all his life, even in Russia. It was from all the associations that he wanted not to be there: "Diaghilev, I hate Diaghilev." Then he loved Denmark “but of course I won't stay in Denmark”. And Lincoln - "Lincoln okay, but at the same time...” He found himself in the States and anchored himself, because he really never liked authority.

You don't much, either.

No, I don't.

You are like him.

Absolutely. I cannot stand authority. I like to make my own mistakes. Even with Lincoln, the person who brought him to the US, can you imagine after all those years, George was never once at Lincoln's home, never once.

Why? Not invited?

Yes, he was invited all the time! But Lincoln was Authority. He organised everything, he protected him, he raised money for him, he built the theatre for him, he built the school for him. That essence that somebody is doing all this for you - they were very cordial, but very non-friendly. At least the last 30 years. Suddenly it was a business kind of thing. Lincoln arrived with his black suit, then they'd have important meetings, him and George and Jerry, but it was never, ever... Actually Balanchine was much closer to Robbins, who personally he didn't like that much. He admired his talent in certain pieces. So both men were very foreign to Balanchine, but at the same time very very very helpful.

That was the great, fantastic story in 20th-century ballet, the relationship that Lincoln Kirstein offered Balanchine.

A romantic, beautiful vision.

Watch Baryshnikov dance Basilio's solo from Don Quixote

The Superstar

Do you watch tapes of your younger self?

No. [quiet]

Never?

No.

Don’t you wish you could have seen what we all saw?

Yes... probably it would be interesting. I never really wanted it. It’s a bit queer, I kind of... I watch myself, tape myself in new work in rehearsal, and I study it through the weeks, and I’m interested just in terms of improving something, but I didn’t do television for many years, because I felt, first, it doesn’t give true justice to the dance, and it’s so much headache that it’s really not worth it. Actually I felt that my work improved, as limitations came and took over my physical approach, because when you’re full of blood you have a tendency to overkill, to overdance always. When you’re young and eager, it’s difficult to keep it less, because you want more.

The public wants more too.

Yes, but sometimes they are badly advised too. Because they are looking for a sensationalism in the physical approach.

But that is valid - you are a prime exemplar of its huge attractiveness.

Yes, but I didn’t push it further up than Vasiliev or Nureyev or anybody else. For a few years I overdanced a lot of stuff, being silly, being foolish, being too cocky, kind of - but it’s interesting, that we actually have to be thankful to all this ice skating and gymnastic routines, that they show us this stuff so much superior to us. Dance is something else, and you have to look into matters of dance and subtleties of dance and inspirational matters of dance. The turmoil and difficulties and excitement of being with City Ballet for a couple of years also kind of shifted my brains. What Balanchine was asking me to do was very contradictory to what the press wanted to see me. You know, “Go on, do your classics, we want to see you in Swan Lake or Giselle, this is not your milieu or your theatre, you are wrongly cast.” But I was a mature dancer, in my late 20s, I really had nothing to lose, and it was the most fascinating experience.

Do you remember that feeling, when you thought you could do anything?

Oh, yah. Especially when I felt totally at home in a production, and you’re having fun with it. You felt, well, I can take any chance I want, whatever happens will happen. And it’s fun and easy and it’s surprising.

What shows made you feel like that?

Oh... I don’t know, maybe some stupid little piece, like dancing with Makarova or Kirkland. Like an old piece like La fille mal gardée - not Ashton’s, I mean - or Coppelia.

Do you think the public expects the wrong things from dancers?

Hm. I don’t know what the public expects from me or from anyone. They want to be entertained. They are going for an experience. You know, when I am in the audience I wanna be moved, I wanna remember something from it. I remember some performances 20, 30 years ago that are always in my mind. I still remember how I felt, what kind of effect those performers had on me, how they affected me, changed my life. If there were one or two people in the audience who felt like I used to feel when I saw that, I would be happy.

It is so rare to feel like that as a viewer - it is a kind of ecstasy. One doesn’t feel like oneself any more... But back to fame. I have seen pictures of you where it is just you and all these cameras.

It is so rare to feel like that as a viewer - it is a kind of ecstasy. One doesn’t feel like oneself any more... But back to fame. I have seen pictures of you where it is just you and all these cameras.

I don’t know. I am used to it. And there are some days it is extraordinarily irritating, and there are some days when you acknowledge it and don’t even think about it. It depends on your state of mind.

Our problem in Europe is that we are mostly familiar with your videos where you are the classical exemplar par excellence, whereas in America they are all very aware of this transition and change you made into modern dancing.

My audience in America now is quite different from what it was - I would say 75 percent of those people who come now to see me dance never saw me in a classical role. I am a modern dancer to them. So you see, they cannot compare. For my first season here with White Oak it was not exactly a disaster but the press jumped all over me. I danced Paul Taylor, Mark Morris and Graham, and the last time they had seen me was in Giselle, so they couldn’t take it. But the next visit, a year later, practically the same repertoire, was a great success.

But that maybe was because it was so rare to find a dancer who was so convincing in classical ballet, a really powerful advocate for its magic. So I hope you will forgive people for seeing you as that legend.

But I was 40 years old, already. What could I have done more with classical dance? Tried to be a director? Or tried to stage my version of Coppelia or Sleeping Beauty? That was not the way I wanted to end my life. With all due respect and love to Anthony Dowell, I would kill myself rather than do something like that. To run a company and do the schedules and casting... it’s really noble work and an extraordinary challenge, but aargh! [pulls a face]

And I was going to ask you if you wanted to run a large company again!

Are you kidding? No. No. Because I really want to learn, not to teach.

You found being player-manager at ABT too much - maybe it’s too much for any dancer?

Rudolf tried it, a lot of other people did. Erik Bruhn for a while. And I realised the biggest pleasure I have is still going on stage. Even some negative moments of certain experiences in the distance are accumulating positive things now... well, let’s say, my experience with Balanchine when I was getting strange notices that I didn’t fit into the company, it was a waste of time. Nonsense. It was one of the most positive experiences for me for later on, for running a company like American Ballet Theater.

Alessandra Ferri said when you ran ABT you were a dictator.

Yeah? Well, she needs one, she needs one [caressingly]. Everyone runs a company in a different way, but when people are using public money they have always to prove that any decision they make has the director behind it. They always ask you what the hell you did with these few pounds or dollars. They are much more spooky of press reaction, what sort of decision a director made, why this and not that. You have to defend your decision all the time.

What are you proudest of at ABT?

That I gave certain dancers a second opinion, how it can be done, about where their careers could lead, a view from inside, and hope. You know, dancers have a bit of tunnel vision sometimes. But what's a dancer's aim? To be free and interpretative and happy, and a pleasurable person to watch on stage.

Amanda McKerrow and Susan Jaffe both told me how much they enjoyed being in your company, felt they’d been given new confidence. You almost created a new generation of American ballerinas.

Well, because I was trying to stay away from commercialism, before you'd contract Fracci or someone. It’s not that they were not great people, Erik Bruhn, Anthony Dowell, wonderful, Rudolf, but this is not a great example for young dancers. It would always be there first, attention suspended through the rest of the company.

Well, let’s look around the world at classical ballet - what do you see?

It’s a bit sad, because of a lack of leadership among the big companies. This vacuum with the departure of the big choreographers, a tremendous vacuum. There are a few talented choreographers who work with the classical technique on point, but not yet on the level of the big masters like Tudor, like Balanchine, like Ashton.

The leadership is taken over by boards now, not artistic directors and choreographers.

Well, it’s unpleasant for any artistic director being told he cannot do this, cannot do that, must think about what’s most commercial and not about what you think is right. It’s everywhere. I'm not sure that I'm generally the right sort of person. But it's back to the ABT conversation. I know I can make a difference, and I know I can add some excitement to the picture and it would be different - but it's the system, any kind of system.

I think it should interest a whole new generation of dancers to give justice to why ballet’s beautiful, why it’s complex, why it’s pure, why it works

You know, I work a lot - in Paris, say, I have a little apartment there, and when I go to Europe I go to class with Paris dancers. And I see how the government structure works. Some things are recognisable from my early years with the Kirov, or my even earlier years in Riga when I was a kid participating in a small, regional dance company. Kirov, commercial theatres of the West, private Balanchine enterprise, or big metropolitan theatres like Germany or France or England. You know, that position of "General Intendant" [laughs]. If you are not a choreographer you are doomed to that link between board of directors and being Mr Good Guy or Mr Bad Guy. It would be always somebody on your side, or against you. And I'm just not interested in the game of it.

OK, where are the good examples going to come from? People think the ballet is doomed, because young people don’t want to do that kind of training regime, because the stories are not being renewed, because ballet is becoming a kind of tool for modern dance, sucked in, taken somewhere else.

[Pause] I think... it’s obviously a bit on a slope, but it will come up, a bit of renaissance in next 10 years I’m convinced [speaking in 1996]. It’s a matter of somebody tastefully renewing the spirit, the interest, not just another production, another interesting designer. I think it should interest a whole new generation of dancers to give justice to why it’s beautiful, why it’s complex, why it’s interesting, why it’s so romantic, why it’s pure, why it works. It’s not the dancers’ fault or choreographers’ fault but it was a bit of a business in the 70s and 80s, done too much, and maybe not too well. Audiences get really tired of another Sleeping Beauty or Swan Lake not well done, and so do dancers.

And for the person who is 17, 18, 19 years old in dance, whom to trust? Especially here in the US. There is no relationship between pupil and teacher, they take classes here and somewhere else. This means if you don’t have an attached experience with a teacher or choreographer - let’s say like Cranko had with his people, or Ashton and MacMillan with their people, Béjart, Kylian. Then you kind of are between two chairs, waiting for your chance. This means you rely on the reaction of the audience, of the critics, to try to figure out what to do. It’s a very fragile thing for a young dancer. But you also see it in older dancers, that companies treat them like children, they don’t learn to take time out, experiment.

I notice, from the years at ABT, and looking at the structure of others, that the more dancers united as a group in a big company, as opposition to the management, rights, working conditions, etc, the more management treated them like children. It’s a group mentality. It never happens in modern dance companies, because they come to the choreographer already a bit more mature, they know what they want as individuals, they are more inquiring, they admire this person’s work and want this experience. It’s a little bit easier with big stationary companies, like Paris, London, Russia, they stay home most of the time, have their own life behind the company. But in touring companies like the US, dancers spend seven, eight months on the road from very young, in hotels, and it’s a very tough job, very tough.

Does Mark Morris offer American ballet a future?

Does Mark Morris offer American ballet a future?

I think he is marvellous. I maybe don’t like all his pieces but I think he’s one of the most talented people from his generation, for sure. Drink To Me Only With Thine Eyes for ABT was solid, and personal, and very very quirky and interesting, rhythmically and visually, a strange piece. I really liked it. (Left, Baryshnikov and Kathleen Moore in Morris's ballet, photo by Eve Arnold from her book with John Fraser, Private View)

But you know, I’ve been criticised all the time I was inviting these people to Ballet Theater. People were saying, “Oh, why are you bringing these downtown choreographers to the Metropolitan Opera House?” David Gordon, Karole Armitage, Taylor, Cunningham, Mark, Twyla - now every company in the world has work by modern choreographers. I think it’s a bit of a vacuum, that Tudor, Balanchine, Ashton, all of a sudden these people were gone. Now all over the world it’s Billy Forsythe, Kylian, in Australia, San Francisco, Europe.

It’s like Holiday Inns all round the world. Do you think there will be a natural move away from classical to modern dance, because people’s training is changing and mixing up and is not so strictly traditional?

I notice the past 20 years there was a gradual sloping down of classical because of the departure of the big choreographers. Everybody was writing about it, everybody was speaking about it, until probably just a couple of years ago there is again interest in the big classical companies, more money for it, new blood. Even though we are still waiting for the next Ashton or Balanchine or Tudor. But still, suddenly the dancers get better - there’s beautiful girls at the Kirov Ballet, or a beautiful boy at the Paris Opera, and a new choreographer, and suddenly now something might happen. You know. It is just up and down, and I don’t know what triggers it.

Watch Baryshnikov dance Twyla Tharp's Push Comes to Shove with Elaine Kudo and Susan Jaffe - the landmark 1976 crossover work for ABT where ballet fused with modern dance

Modern Times

What comment most pleased you about your dancing?

The most complimentary thing is not what critics or audiences are saying but my relationship with choreographers. I never had one problem with one choreographer, and I was blessed that I caught up with people like Sir Fred, and Antony Tudor, and Balanchine and Graham, working with Jerome Robbins and Twyla Tharp and Kenneth MacMillan, and that’s the relationship I value the most. And I’ve been part of many creations.

How difficult was it to change style between classical and modern?

Ah, style [dismissively]. I’m just a dancer. And I like to succeed, try to succeed in everything I try to do. I don’t think of myself as a classical dancer, a modern dancer, a character dancer, or an actor dancer. I’m a dancer and that includes everything. Just because I was deprived of it for so long, I discovered modern dance in my mid-20s, it took 15-20 years of apprenticeship to try to understand certain choreographic styles, and my admiration and love grew gradually through the years.

Do you respond differently to the two, does it drawn out different sides of you?

I would say modern dance is more exposing, your personality is plainer, because you are right in front of the eye. It’s a less mannered form of movement, and you remember Martha Graham used to say the body cannot lie. Classical and romantic ballet is really a form of style where it’s easier to separate yourself from the audience.

But the more artificial the ballet, the deeper the human truths in it, which is why the audience keeps coming back to it. And that’s something that very few dancers recognise and achieve. They hide behind its technique.

Yes, probably you pushed the right button, because very few dancers understand that even in the most mannered form of dance you have to be the most simple. Usually they exaggerate the aspects of this or that tradition and it becomes a mishmash. But back to your question, I found that from purely personal experience I can relate to the modern material on an everyday basis, from my age, my physical condition, I don’t have to run after something or hide behind something, I just can be myself. I am always modifying my repertory and choosing pieces that I feel 100 percent comfortable in, and can do some justice to it, whether it’s a solo or a group piece. Not fighting the material, not trying to compete with myself, or my past. That’s why every year I’m trying to do three or four new pieces, so I won't have to do something made six years ago.

How much do you expect of yourself now as a dancer? Do you still jump and turn?

Of course. It’s like a musical note - I can dance between the lines, the upper limit and the lower. I don’t jump as much up here or squat down so much down there, but in this octave I can do 100 percent. And if the choreographer knows that, there is no limit. (Right, publicity picture by Annie Leibowitz for the White Oak tour)

Do you mind that a lot of audience are people who watched you when you were in the classics?

Um... no. I really care what they feel after the performance, and I really believe that if you truly like dance, you are - say - a ballet fan, a ballet lover, you really can appreciate any form of dance. Maybe it would not be your favourite cup of tea but if you like tea you’ll have a certain satisfaction.

You’re educating a fairly conservative audience.

But this is not my mission, I’m just trying to give them choice from my point of view as a member of the audience, what I would like to see. I am not trying to be too self-important - dance is entertainment. Of course there are some that are more serious, but we are trying to give people quality of dancing and justice to choreographers.

Opportunities for younger choreographers are limited in the US?

Oh, they are. Government support has had drastic cuts, Federal and national endowment, makes it difficult. In New York there’s always something happening, full of little places where people are showing their work, downtown, Dance Theater Workshop, the Kitchen, and still the most needed occupation is a good choreographer - in Europe too. Now there’s plenty of dancing talent, but especially in classical field, a little bit more than in modern dance, the driving force is of people like Cunningham, Brown, Childs. This is why ballet companies are opening doors to modern dance choreographers.

What keeps the White Oak Project going?

It’s an unusual, very flexible and mobile group. There’s always something interesting happened, and if it gets bored, then it will be over. There are not that many repertory groups around, usually it’s one person’s vision.

But without you and your fame, would Hanya Holm and Limon get danced?

[Pause] Maybe not... I think that this kind of group can exist without me, but it would be a different kind of audience. Maybe this kind of group wouldn’t exist otherwise without some kind of, um....some kind of financial support. We don’t have any. All our profit comes from box office, we don’t have sponsorship, not one dollar of national support. Sometimes we are happy and we have a spillover from touring, and we will invest that in the next project immediately. If we don’t, then I will put my own money into it. So it means we are gambling, and with my presence it’s a bit less of a gamble, but it’s an unfortunate responsibility to have to sit and talk to you - not that I hate it that much, but I have to sell tickets. And back to your question - I really truly believe that our dancers could sustain the group by themselves, but it would be a different audience.

You can carry on dancing because you decided to change your idiom from ballet?

I just lost it, six, seven years ago - said there’s no sense continuing in this direction. First of all I started doing solo work. That’s the tradition in modern dance, choreographers did pieces on themselves, Duncan, Denis Shawn, Limon, Cunningham, Taylor. And I never had a chance through the past years to do more on smaller stages. It’s a different concentration. It was an extraordinarily satisfying experience... because of certain physical limitations, the injury, age, whatever it is, my mind started to work and look at dance in a different angle, what can I achieve with certain phrasing, desired shape, attitude, etc. I felt my work improved, as limitations came and took over my physical approach, because when you’re full of blood you have a tendency to overkill.

It’s much more difficult with the simpler steps to take the audience to your spell, and the spell of the choreographer

Have you always been this thoughtful about dance?

Mmm, maybe not in my early years, because you are very cocky and very sure about yourself and you know, it’s part of your youth and ignorance. But just by working with choreographers and answering their demands, you analyse who you are, and what their perspective is on you, and what they suggest, and how you can relate to certain matters.

Very few dancers have that confidence. Most of them identify themselves by their look, their style, and they don’t want to risk changing it in such a short career.

It’s the most difficult thing to do less. It’s the most difficult thing.

They’re frightened of losing the one thing they have. I was talking with a young virtuoso dancer in England, who is scared to put his own personality into what he does, because of what the public expects of him.

Yes, I think that’s the critics’ responsibility. Because whatever a critic may say about whether a choreography is right or wrong, choreographers are mature people, they stick with their own internal agenda, and no matter whether critics love or hate their work, they will be around if they want to choreograph, especially if they are good. But dancers, when you are 16 or 17 years old, you are very much in the hands of your audience and critics, and much less in the hands of your artistic director. Because every young dancer is eager to be successful, and very often critics lead in one direction - sometimes parallel with the audience’s need - and the artistic director pursues a different direction, and at that point it can be difficult to understand how to go.

What would happen to you if you stopped? To your body? To your mind?

I really don’t worry that much, because I think I can be involved, I know how to put people together. I might be involved in producing for other people. Maybe the same group can exist, but me being backstage and creating situations, and bring choreographers, and doing the workshops. I learned I’m pretty good at that, I learned the business side of it, I know organisation. My priorities are shifting. I don’t know what I am doing a year from now, because the minute you commit, there’s no way out. There’s always interesting people approaching us with work, or we are on the waiting list for someone. I don’t understand how singers and conductors can know what they do five years from now. I mean, slavery!

Yes, but also reassurance. Because Clint Eastwood and Luciano Pavarotti can go on being heroes at 65.

No, but it’s a different life. Dancing is such a fragile experience, even from the start.

Who tells you now when you are dancing well or badly?

Um. Well, we are watching each other, more or less, and usually choreographers come and work with you. But you have to be brutal in dance. You sometimes ask people whom you trust, take a look at what I am doing, which parts look sloppy or overdone or not musical, things like that. So you do need someone else to look at you. You can’t do it yourself.

Does it scare you now, that you might not do something right and someone didn’t dare tell you, because you are a big star?

Maybe it’s less noticeable [when things are wrong in modern dance] than to land badly from a double tour to arabesque on one leg, maybe it’s less visible. But at the same time it’s much more difficult with the simpler steps to take the audience to your spell, and the spell of the choreographer. It’s in many ways more difficult.

How honest are you with yourself about your dancing?

Ah... I try to be.

Monica Mason said she had to see herself on video before she knew she had to stop.

But classical ballet is such a fierce standard, and it’s a shame dancers give up so young, but dance is more than detail, it’s something in the way you move. You really must be careful with the material. The material which I am doing I never compromise on. Not a single percent. In a way, doing all these solo concerts put me back on my toes physically, because to dance three or four big solos a night is quite a task, whether for a younger person or for an older person like me. It’s more than an hour of solo dancing in an evening. I just love it. I can stop it, any time. But now I think the work is more interesting - I am working with really wonderful people, back with Mark Morris, and Trisha Brown. Merce Cunningham wanted to do something with me, and you know [smiles] my hair stood up from excitement. It doesn’t happen that often.

Sylvie Guillem told me that an image and a name can be an obstacle sometimes to get a new choreographer.

Well, I don’t know. It takes patience. You know, the choreographer has to trust that you will do justice to their work - that’s what they care about. Because if they are a really good choreographer they don’t need you to push their work. They don’t want to be hassled, they care that you do justice to their piece.

Do you have many choreographers approaching you?

Some people I go after. I watch a lot of videos - people send me their work a lot. But I go to see as much as I can, in the States, in Paris or wherever I go. But it works both ways. Like Mark says, let’s do something, or Twyla. Or Jonathan Burrows - I like his work and he was interested to do something, but of course he is a very busy man, teaching in Belgium, and trying to figure out how in the near future he can do something for me.

It’s the working that gives you the fulfilment, rather than the performing?

I always liked to work more than to perform. I am a very nervous performer. I am very exhausted after a performance - I really burn myself up prior to it because I am so chicken.

The audience frightens you still?

The idea that someone paid some bucks to see me dance. It takes a lot of chutzpah to go and really make people feel good and give them something worth their money, or some emotional memory. I am not trying to be coquettish about this. It’s psychological. There is nothing I can do. I should go to the shrink because of this? No, I go on stage and do my best.

You gave a great disguise then.

Well, thank you. I am trying to. I am trying to learn a bit of minimalism from others, try to learn different concentration in solo work - Sarah Rudner, Dana Reitz, Meg Stuart, Trisha Brown, don’t know why it’s all women but maybe they have more patience with themselves, they are endurance performers.

What would be the nicest surprise anyone could give you in your career? It looks like a perfect career. You have achieved much.

This year started on such a high note, in terms of future plans, that I am kind of amazed. There is a Russian saying: “God forbid it should be better.” It’s like saying, don’t let this change. Because historically people in the Soviet Union were always promised it would get better and yet it always got worse and worse. So they would pray, don’t let it get better...

Playing Aleksandr Petrovsky in TV's Sex and the City with Sarah Jessica Parker

The Philanthropist

[2004, interview in his room in the Holiday Inn, Holyoke, Massachusetts. A large copper tub filled with booze and snacks has been sent up to him - he says to me, animatedly, how nice it would be to "hold potatoes". The tour, benefiting the Baryshnikov Arts Center, presented Michael Clark’s work for Baryshnikov in which they danced together, Rattle Your Jewellery.]

Did you have a big breakfast?

Yes!

Not a Super Sizzlin' Lumberjack?

No. [Laughs.] Eggs and sausages.

You’ve set a lot of time aside this year. This tour is for the arts centre foundation?

It's a continuation of the last year's tour. Then I hurt myself, and it took me six months to recover. Operation - left knee. The knee which had not been operated before. It was a really speedy recovery. Then I did this new piece with Elliot just to get myself going, and now I'm shuffling the preogramme according to my state of health and age! I stopped White Oak functioning last December because I really couldn't be in two chairs at the same time, raising money for the centre as well. That was after 12, 13 years, and the group was evolving into something else. And I'd been away from home too long. At the same time my appetite for performing was still high, and I started working on new pieces with Lucinda and Cesc Gelabert and Tere O'Connor, without thinking where it would lead to, but this tour emerged. We'll have the building done in just a couple of months. It's amazing.

When you ask a choreographer like Lucinda or Michael or Cesc, do you say, you have a free hand, or do you say, this is for me?

Well, Michael and Cesc are my new friends, so to speak. Lucinda and Tere are choreographers I've worked with for many years, they know me well. Like this piece from Lucinda, I'd just asked her to think about it when she had time between opera and her pieces in Europe, if she was interested in doing something small. She said, okay, I'll listen. And I was in Europe - there was a recital in Villa Borgese in Rome, this French pianist was playing this Berg sonata. And I thought I knew pretty much all Berg, but this sonata is apparently very rarely recorded, and I really fell in love with the music, and I sent it to Lucinda. She said, this is really wonderful music and I'd like to do a piece. Well, you know! Things happened. And I kind of knew I'd like to go with the single instrument, something whose proportions lead to what I do now. I feel that I have a connection with somebody playing right there - an immediate connection.

It's like a Lieder recital - a singer, a pianist, they have the world.

Yes, exactly!

Is the arts centre the big thing in your life now?

No, but I always try to combine, be sure there isn't a big gap between good living and good working conditions. I figured out the formula: luckily I know it will be sold out, and it will make this much, and the cost will be this and this, and so I think, why not? It's like the old Jewish joke. Two men meet. One says, “I didn't know your daughter was married?” “No, she is not.” “Well, I passed the house and she was sitting feeding the baby.” “Well, if you have a little bit of time and a little bit of milk..." I just have a little time and a little bit of milk!

A joke comes to mind: the old tired worm that falls into a bowl of spaghetti thinking there's an orgy there

I think I had a love-hate relationship with New York for 30 years. The first few years were most exciting - when you are single and you are young and free, New York was the most amazing place to be and to work, in Ballet Theater with different choreographers, Alvin Ailey, Twyla Tharp or John Butler or somebody. It was fun for a while, and then... I got disappointed about many things. About New York. About the States too. You know, it's very frustrating, sometimes you go and visit Europe and see good old socialism in its good part. Certain things In Italy or in Germany, or in Paris or in London. You see public concern about art, and young people's participation and faces in the audience, and then you arrive in the States and it's $150 to go and see a Broadway show or opera. Ridiculous.

Which brings us to TV and Sex and the City. Was it part of the strategy for fund-raising or a challenge? Because it's made you tremendously famous with a new audience.

Erm... [laughs]. Another joke comes to mind: the old tired worm that falls into a bowl of spaghetti thinking there's an orgy there, ha-ha! I don't know why I suddenly remembered that old joke. But it reminds me of my experience of Sex and the City.

More spaghetti than orgy?

More spaghetti than orgy?

More spaghetti than orgy, yes! You know what, I don't know why I did it. [Laughing] My wife thought it would be interesting maybe - as well! (Right, Baryshnikov and his wife Lisa Rinehart)

Are you embarrassed by it?

[Stops laughing] No. I'm not at all. Because I always do things I'm kind of scared of. I push myself towards things that are unknown, that might not sit quite well with me. It's instinctive that if I am afraid of something I have to face it one day.

What were you facing in Sex and the City?

The pressure of working very fast and very hard with a few very good actors. Which is a very extraordinary learning experience. I did nine episodes, I worked with seven different directors. Sometimes with only two episodes, switch to a new director, a new director [snaps fingers]. If you want a straight answer, I really don't know why I did it [laughs]. My character is just a bit of material for them to do this with or that. They just need a little bit of fresh meat! Some people say I'm crazy, but it's great if you can learn something. I'm doing theatre in the spring, and it's a kind of psychotherapy for me about my hesitant... attitude towards, you know... camera. Dance is a silent art, and here, you know, I have to face people, I have to go in front of audience, and say a few things.

Worse in front of camera?

Oh my God, it's very hard. On stage you rehearse a minute for days, and for dance for 20 seconds you might rehearse for a week. Here you do pages and pages in hours.

Do you have any idea when you knew you had the gift of communication?

Communication on stage? Um...

Because that's why it still works.

I guess... it's not in me. I really always had that admiration for the choreographic craft, that if somebody has the vision to put a few steps together and make a dance out of it, there is already a certain power implanted. In a way, my job is much easier - it's just to put a light into it.

Add comment