Is Gounod’s Faust really a “complex and multi-layered work”, as director Jack Furness claims? Goethe’s original and Berlioz’s Damnation, absolutely; this tuneful concoction, half light opera, half kitsch melodrama, not so much. If Furness’s take leads him to concept overload, as well as quite a few really strong ideas, the big strength here lies in the casting of three world-class singers in the eternal triangle of rake, seduceable innocent and devil.

The old, suicide-bent Faust’s crisis of scientific knowledge leaving a religious void causes Furness to set the action in a late 19th century industrial town, complete with designer Francis O’Connor’s striking factory windows to the right and smoking chimneys, one of which transforms into a great uplifted gun as the horrors of the First World War are rammed home (the usual cliché of soldiers on crutches undermining a jolly chorus). It can all feel a little crowded on the stage of Dublin’s lovely Gaiety Theatre, a perfect equivalent to the Parisian auditoriums where Gounod’s opera had various successes.  Within all the business, not least of a vocally strong chorus not able to move around much and confined to production-line work when Gounod wants them to waltz or frolic (and the make-up generally is way over the top), there are some admirable gambits. Real sparks and smoke, shattering swords and wilting flowers, for a start, and the casting of an old Faust (Nick Dunning, excellent, looking like a grizzled Donald Sutherland) as well as the handsome young one he wants to become (Seoul-born tenor Duke Kim, yet another supreme, live-wire talent of the many in every musical field pouring out of South Korea, pictured above with Dunning). This isn’t just a convenient way of avoiding senile make-up on a youthful singer, but carries through to Old Faust’s reactions when his irresponsible rejuvenated form is about to overstep the mark, and a fine marionette-dance to Mephistopheles’ serenade. Not to mention the final idea, and I won’t specify it because that would be a spoiler.

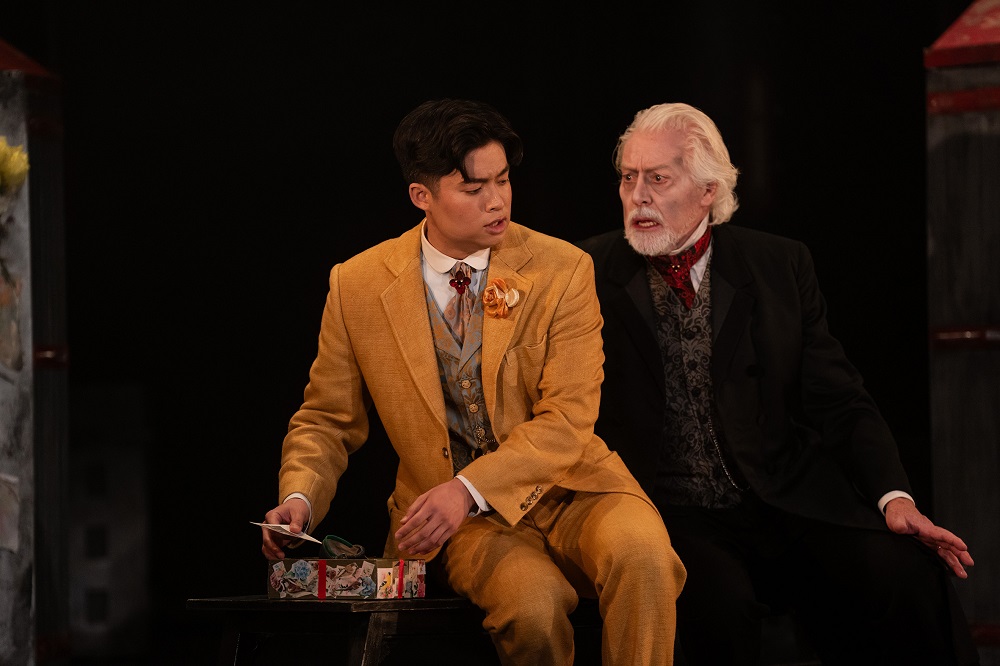

Within all the business, not least of a vocally strong chorus not able to move around much and confined to production-line work when Gounod wants them to waltz or frolic (and the make-up generally is way over the top), there are some admirable gambits. Real sparks and smoke, shattering swords and wilting flowers, for a start, and the casting of an old Faust (Nick Dunning, excellent, looking like a grizzled Donald Sutherland) as well as the handsome young one he wants to become (Seoul-born tenor Duke Kim, yet another supreme, live-wire talent of the many in every musical field pouring out of South Korea, pictured above with Dunning). This isn’t just a convenient way of avoiding senile make-up on a youthful singer, but carries through to Old Faust’s reactions when his irresponsible rejuvenated form is about to overstep the mark, and a fine marionette-dance to Mephistopheles’ serenade. Not to mention the final idea, and I won’t specify it because that would be a spoiler.

Gounod’s first three acts begin in fustian style and then become a stream of melodious set-pieces. Nothing palls here thanks to the immediate vocal lustre of young Kim as well as the admirable, singer-conscious pacing of INO’s resident conductor and chorus director Elaine Kelly, as good at the perfumed lyricism as she later is in the Gothic overload. We know Kim’s going to manage the crucial top C in “Salut, demeure chaste et pure” from what he does in the Kermesse – read here bomb-manufacture – scene, and he not only hits it with the sweetest fullness, but does a perfect diminuendo on it. He’s handsome and a good actor, too. How could a major international career not beckon?  It already has for Irish soprano Jennifer Davis, now in demand for Wagner’s more lyric roles since her stunning Elsa in the Royal Opera Lohengrin. She has both sides of the insanely demanding role of Marguerite in her armoury: the bright, rapturous virginal candour for the Garden Scene arias, quartet and duet, and the big organ stops pulled out from the hoary church confessional scene onwards. The prison finale not only looks perfect, seared on the mind, but reaches a rare zenith of operatic perfection as her trio tune peals out, each time intensified as it goes up a notch. Opera thrills don’t come much stronger than this.

It already has for Irish soprano Jennifer Davis, now in demand for Wagner’s more lyric roles since her stunning Elsa in the Royal Opera Lohengrin. She has both sides of the insanely demanding role of Marguerite in her armoury: the bright, rapturous virginal candour for the Garden Scene arias, quartet and duet, and the big organ stops pulled out from the hoary church confessional scene onwards. The prison finale not only looks perfect, seared on the mind, but reaches a rare zenith of operatic perfection as her trio tune peals out, each time intensified as it goes up a notch. Opera thrills don’t come much stronger than this.

If Nicholas Brownlee is more bass-baritone than cavernous bass as the very devil, he too has imposing presence, the right ability to amuse and turn nasty. There’s real quality and intelligence in Gemma Ní Bhriain’s Siebel – with the mezzo’s ringing top, one foresees Strauss’s Composer and Octavian around the corner. The one vocal weakness of the evening is in fact over-strength as baritone Gyula Nagy delivers the pure commendation of Marguerite’s brother Valentin in too iron-clad a fashion, but he helps heighten the intense drama in Act Four (pictured below: the dying Valentin curses Marguerite).  Certainly Furness makes sure the screw truly turns, with emphasis on the support of Siebel and Marthe (a personable veteran turn by Colette McGahon) for a poor girl in trouble, and a Walpurgis Night scene inevitably shorn of all but the last of the ballet numbers (putatively by Delibes) for a hallucinatory condensing which involves Faust injected by devilish WW1 nurses to fantasise about Cleopatra. The divertissement would, in any case, slacken the tension which is sustained here to the very end. And what an end.

Certainly Furness makes sure the screw truly turns, with emphasis on the support of Siebel and Marthe (a personable veteran turn by Colette McGahon) for a poor girl in trouble, and a Walpurgis Night scene inevitably shorn of all but the last of the ballet numbers (putatively by Delibes) for a hallucinatory condensing which involves Faust injected by devilish WW1 nurses to fantasise about Cleopatra. The divertissement would, in any case, slacken the tension which is sustained here to the very end. And what an end.

Add comment