There are so many good ideas, so much talented hard work from the singers of the Jette Parker Young Artists Programme and two dancers, such a cinematic use of the Royal Opera House, that Isabelle Kettle’s interweaving of two Brecht/Weill mini masterpieces ought to work better than it does. In jettisoning much about the fantastical scenarios of flawed human beings on quests to make or spend money in paradises that turn out to be hells, favouring instead the deconstruction of female and male archetypes, you need to be clear about your intentions, streamline their presentation. Too often here the viewer will be asking “why?”.

Not that the original 20th century myths are always easy to clarify. Brecht’s words for Anna I, a singer, and occasionally for her alter ego Anna II, a dancer, in their journey to subdue the seven deadly sins as bourgeois morality has it – pride in one’s art, anger at injustice, and so on – are better than some of the original stage directions for how these play out in seven American cities. Most productions find their own solutions, with in some cases this “sung ballet” of 1933 jettisoning the dance element (Weill’s music is strong enough to carry the absence). It’s here in Kettle’s thoroughly modern treatment, in the shape of the charismatic Jonadette Carpio (pictured below on the right with Stephanie Wake-Edwards) as choreographed by Julia Cheng. Kettle is clever to divide up the qualms, neuroses and ultimate breakdown between Anna II and Anna I, contrary to the latter’s claim that “she’s just a little mad, my head’s on straight”. By the time of “Gluttony”, dancer Anna basks in a fantasy woodland picnic while singer Anna acts out an eating disorder; then the pills and the booze are the problem of the “practical” one.  This places a huge acting burden on mezzo Stephanie Wake-Edwards, last seen singing Weill in the Crush Bar with Antonio Pappano as pianist, and she carries it off superbly. First captured by hand-held cameras leaving her real dressing room for the one that takes up half the stage – canny designs by the excellent Lizzie Clachan – she sees her volatile sister through the make-up mirror. She’s excellent with the text – it was tough on the JPYAP singers that the original German remains, when so often we hear these works in translation – and only needs to marshal the sound more carefully in the softer, more desolate passages.

This places a huge acting burden on mezzo Stephanie Wake-Edwards, last seen singing Weill in the Crush Bar with Antonio Pappano as pianist, and she carries it off superbly. First captured by hand-held cameras leaving her real dressing room for the one that takes up half the stage – canny designs by the excellent Lizzie Clachan – she sees her volatile sister through the make-up mirror. She’s excellent with the text – it was tough on the JPYAP singers that the original German remains, when so often we hear these works in translation – and only needs to marshal the sound more carefully in the softer, more desolate passages.

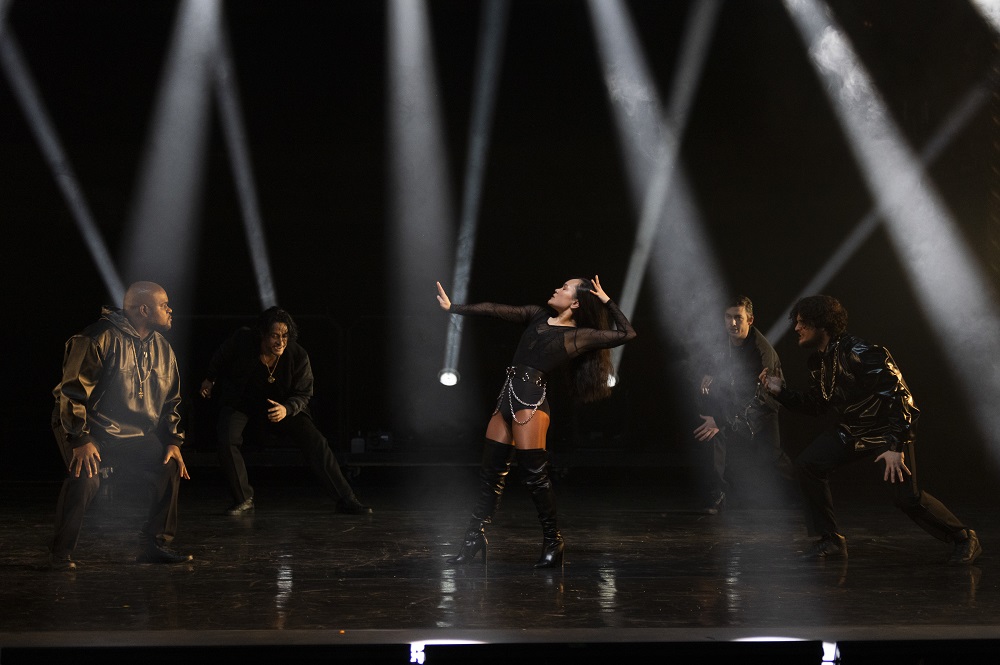

There is no real journey, no “family in Louisiana” to send money home to – Brecht and Weill cast “Mom” as a bass in drag – only an always threatening male quartet asserting dominance in the “real” world. Vocally the four young men handle some tricky part-writing very well indeed; it’s easy to go off pitch in the "Gluttony" barbershop quartet – the "family" in the otherwise excellent Opera North streaming last year showed us how badly – but this stays anchored, with the ever brilliant Filipe Manu solid as a rock on the top tenor line. It’s good that Kettle jettisons the German 1920s/30s obsession with “Amerikanismus” to make this universal. The stage on which Anna II performs to an empty Royal Opera auditorium is cannily, variously lit by James Farncombe, and if what Carpio executes on it isn’t always dramatically clear, she’s always compelling (pictured below in the "Avarice" sequence with Blaise Malaba, Filipe Manu, .Egor Zhuravskii and Dominic Sedgwick). There’s more of a problem with the role of her male counterpart added to the shorter shenanigans of the Mahagonny Songspiel (so much more than just a 1927 preliminary sketch for the full-length operatic Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny; it’s perfect as the opera is not). Is he Master of Ceremonies or fall-guy as the male world so triumphant in The Seven Deadly Sins implodes? Thomasin Gülgeç’s moves (Gülgeç pictured below) are as compelling as Carpio’s – he’s already executed a singular Pas de deux with her in the “Lust” sequence of Sins as Anna II’s true love – but it’s not always clear what he’s trying to say with them in the five instrumental interludes (the last, a tragic chorale where sympathy for the human condition at last emerges, surey needs stillness). Only as he makes his final exit to the centre top of the amphitheatre, spotlit in parallel to Anna II’s walk into immortality, do we get the connection.

There’s more of a problem with the role of her male counterpart added to the shorter shenanigans of the Mahagonny Songspiel (so much more than just a 1927 preliminary sketch for the full-length operatic Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny; it’s perfect as the opera is not). Is he Master of Ceremonies or fall-guy as the male world so triumphant in The Seven Deadly Sins implodes? Thomasin Gülgeç’s moves (Gülgeç pictured below) are as compelling as Carpio’s – he’s already executed a singular Pas de deux with her in the “Lust” sequence of Sins as Anna II’s true love – but it’s not always clear what he’s trying to say with them in the five instrumental interludes (the last, a tragic chorale where sympathy for the human condition at last emerges, surey needs stillness). Only as he makes his final exit to the centre top of the amphitheatre, spotlit in parallel to Anna II’s walk into immortality, do we get the connection.

How brilliantly the six singers execute their roles, though, even if they could do with being in closer proximity to conductor and players. The men are – what, Bullingdon boys?, in DJs who boisterously play football and execute fatuous drunken dance routines on the grassy area where the stalls seats are usually to be found: a clever alternative to the boxing ring in which the 1927 premiere production was set. The women (Kseniia Nikolaieva joining Wake-Edwards, hamming it up deliciously) appear in smeared make-up sporting versions of the frilly pink dress Anna II wore in the “Gluttony” scene. The women are now voracious, vampiric: the male images crumble and even God is dismissed (he’s now wearing a dress – a deliciously delayed homage to the “Mom” identity in Sins). One of the pleasures of any JPYAP venture is to see singers progress, and true bass Blaise Malaba does splendid solo and ensemble work here.  So far, mostly so haunting. But when Weill brings Mahagonny, the dream city for those whose aspirations go no further than gambling, drinking and whoring, tumbling down, there’s only indecisive flailing and running around. A black hole gapes when we need something climactic. Musically, the 11 players from the Royal Opera House Orchestra carry it off compellingly under Michael Papadopoulos (and how good it is to hear the haunting, insidious sounds of the original “Alabama Song” after so many different treatments). I’m not sure that the 15-part reduction of the Sins score by H K Gruber and Christian Muthspiel works so well, and the ferocious passages need more attack here. But there’s room for improvement. In fact, although the singular filmic nature of the production might be a problem, I’d like to see the whole thing reworked for future performances before an audience, with a bit more rehearsal time for vocal precision and a bit less business; there’s too much excellence here to be thrown away.

So far, mostly so haunting. But when Weill brings Mahagonny, the dream city for those whose aspirations go no further than gambling, drinking and whoring, tumbling down, there’s only indecisive flailing and running around. A black hole gapes when we need something climactic. Musically, the 11 players from the Royal Opera House Orchestra carry it off compellingly under Michael Papadopoulos (and how good it is to hear the haunting, insidious sounds of the original “Alabama Song” after so many different treatments). I’m not sure that the 15-part reduction of the Sins score by H K Gruber and Christian Muthspiel works so well, and the ferocious passages need more attack here. But there’s room for improvement. In fact, although the singular filmic nature of the production might be a problem, I’d like to see the whole thing reworked for future performances before an audience, with a bit more rehearsal time for vocal precision and a bit less business; there’s too much excellence here to be thrown away.

Add comment