This show has been a long time coming. Neil Gaiman had the first inklings of The Ocean at the End of the Lane when he was seven years old and living near a farm recorded in the Domesday Book. Several decades later, he wrote a short story for his wife, Amanda Palmer, “to tell her where I lived and who I was as a boy”, as he puts it in his programme notes.

That short story was developed into an award-winning novel; Joel Horwood’s adaptation opened at the Dorfman Theatre in late 2019, and was meant to transfer to the West End in early 2020. Now it’s back, and the spellbinding beauty of Katy Rudd’s staging is more than worth the wait.

We begin with death, and then more, and then more. A man (Nicolas Tennant) has returned to his childhood home for his father’s funeral, and stumbles from there down memory lane, back to his 12th birthday, when he discovered the body of his father’s lodger in the family car. The boy’s mother has also recently died, and his father is trying to keep everything together. An encounter with a charming little girl called Lettie Hempstock (Nia Towle) launches the Boy (James Bamford), who is never named, into a world of magic and peril.

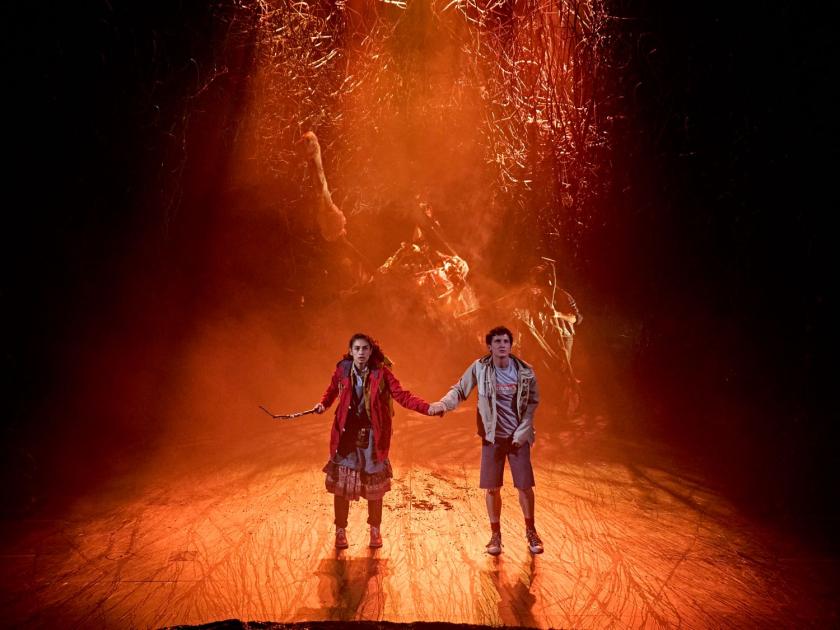

In Steven Hoggett’s flowing choreography, Ocean shares DNA with The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time (which Hoggett, Rudd, and several cast members also worked on). Jherek Bischoff’s pulsing 80s score evokes Stranger Things, as does the show’s typeface. The emotional battery reminds us of A Monster Calls, another novel about a child’s grief transformed into a starkly beautiful production, for the Bristol Old Vic in 2017.  There are other familiar ingredients: a child protagonist who escapes reality through books; an annoying younger sister, played superbly here by Grace Hogg-Robinson; an evil stepmother figure by the name of Ursula Monkton (Laura Rogers). Still, Ocean is anything but predictable. It’s big and terrifying, but grounded in small details. Lettie takes the Boy home to her farmhouse to meet her mother Ginnie (Siubhan Harrison) and her grandmother (Penny Layden), who insists on being called Old Mrs Hempstock: “I was here first!”. Kind in a no-nonsense sort of way, they give him milk warm from the cow and pieces of sticky honeycomb, and warn him of the perils of wearing shorts. “Love a kneecap, badgers do.”

There are other familiar ingredients: a child protagonist who escapes reality through books; an annoying younger sister, played superbly here by Grace Hogg-Robinson; an evil stepmother figure by the name of Ursula Monkton (Laura Rogers). Still, Ocean is anything but predictable. It’s big and terrifying, but grounded in small details. Lettie takes the Boy home to her farmhouse to meet her mother Ginnie (Siubhan Harrison) and her grandmother (Penny Layden), who insists on being called Old Mrs Hempstock: “I was here first!”. Kind in a no-nonsense sort of way, they give him milk warm from the cow and pieces of sticky honeycomb, and warn him of the perils of wearing shorts. “Love a kneecap, badgers do.”

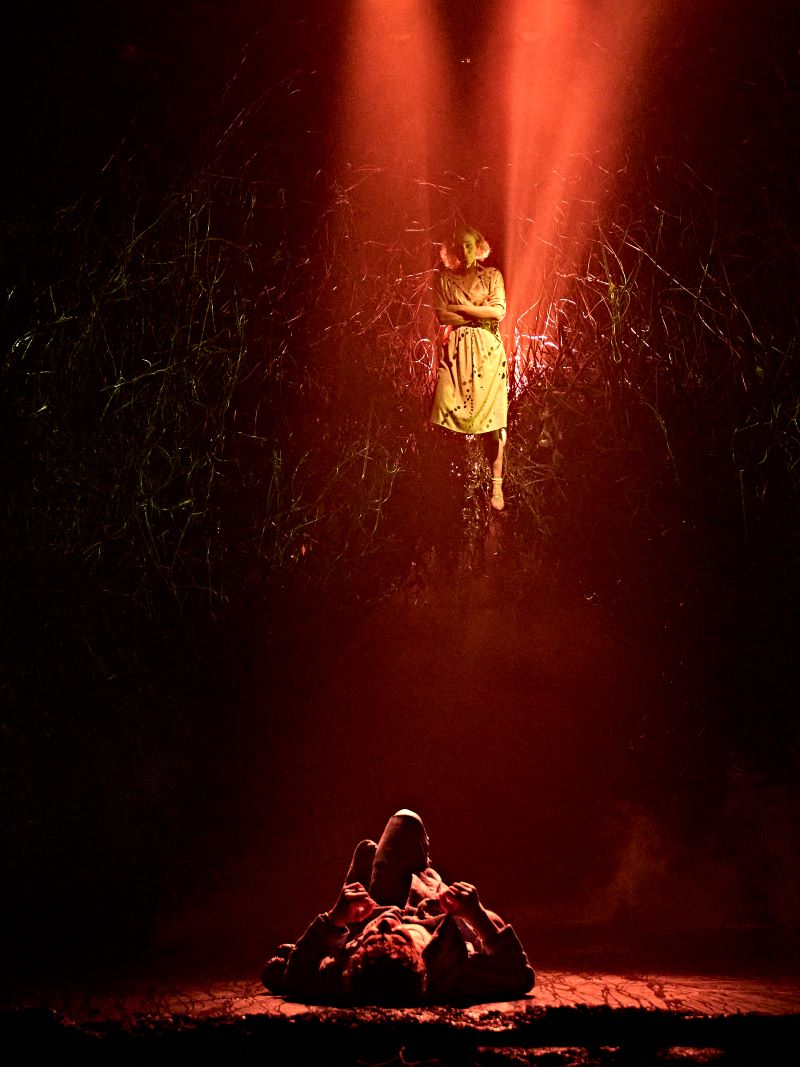

Like the book, the show is about memory, which is half imagination, according to Old Mrs Hempstock. Set designer Fly Davis outlines the doors and furniture of the Boy’s house in white light, as if his recollection stops at their edges. Paule Constable lights the Hempstocks’ kitchen in cosy oranges, camping lanterns suspended above the homely furniture; despite the fantastical danger they bring into his life, their world is a safe place for the Boy.

Weirdly for a show with so many scary moments, the whole of Ocean feels safe – in a good way. Samuel Wyer’s puppets and Jamie Harrison’s illusions delight and confuse in equal measure. This is an ensemble piece, both onstage and off. The meticulously-timed dance of puppets, music, lights and actors makes you want to interview the stage managers.

Weirdly for a show with so many scary moments, the whole of Ocean feels safe – in a good way. Samuel Wyer’s puppets and Jamie Harrison’s illusions delight and confuse in equal measure. This is an ensemble piece, both onstage and off. The meticulously-timed dance of puppets, music, lights and actors makes you want to interview the stage managers.

The most important thing about adaptation is that it’s not rehashing the original medium beat for beat – it’s getting it to make sense in the new form. Horwood has recreated the dreamlike wonderment of Gaiman’s novel, using theatrical rather than literary tricks. Lettie asks the Boy if he wants to come over for pancakes; the Boy hesitates, and the ensemble members moving the pieces of the Hempstock kitchen into place look to him. It’s only when he says yes that the furniture is positioned.

No other production I’ve seen has captured the experience of childhood, the terror and the beauty – not what actually happened, but what it felt like (which is also what adaptation is about). That’s what Gaiman was trying to show his wife in his short story, and it’s what everyone who made Ocean shows us.

Add comment