It is 30 years since Shadowlands, William Nicholson's much-loved play about CS Lewis's unexpected love affair with Joy Gresham, an American poet, was first seen on stage. The famous academic and author of the Narnia books, apparently content in his male world of Oxford high tables and intellectual cut-and-thrust, was transformed by his meeting with Joy, a clever, outspoken fan of his theological writing. Their idyll was short-lived; within a few years she succumbed to cancer and Lewis was overwhelmed with grief.

A new production, directed by Rachel Kavanaugh, opens at the Chichester Festival Theatre this week, with Hugh Bonneville (Downton Abbey, W1A, Paddington) as Lewis and Liz White (Life on Mars, Ackley Bridge) as Joy. Nicholson has dropped into rehearsals rarely, happy he says for director and cast to feel free of interference from "the writer in the room".

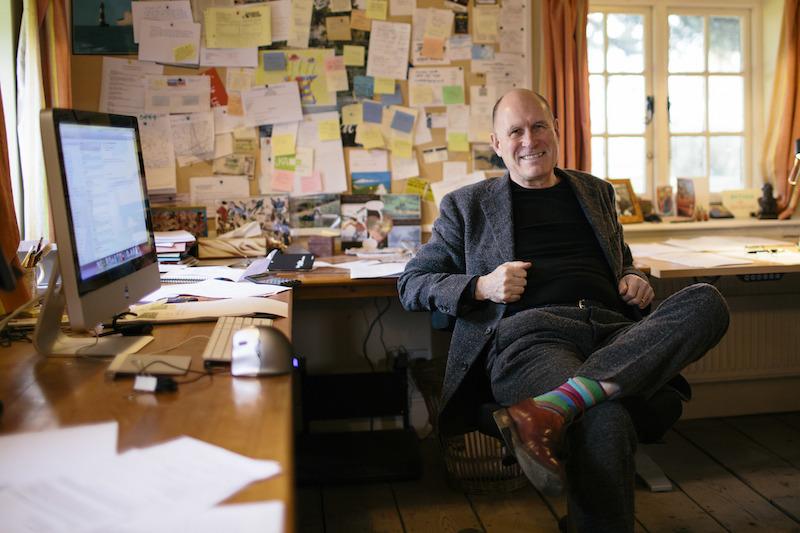

At 71, a successful novelist both for adults and young readers, as well as a playwright and screenwriter (he has been Oscar-nominated twice, for Shadowlands and, as co-writer, for Gladiator), Nicholson is as busy as ever. His most recent project was writing and directing Hope Gap, a film starring Annette Bening, Bill Nighy and Josh O'Connor based on an earlier Chichester production, The Retreat from Moscow, which draws on Nicholson's own experience of his parents' disintegrating marriage.

After a childhood in Sussex and Gloucestershire, he read English at Cambridge, graduated with a Double First, and joined the BBC to make documentaries, including the Everyman series. This involved travelling the world, covering subjects such as Satanism in Hollywood movies and visions of the Virgin Mary in Spain. At last, in 1979, a novel was published and read by one of his BBC superiors who, as a result, suggested he write plays for television.

He lives mainly in Sussex, with his wife, the social historian Virginia Nicholson, and their three children, but we met at his London address during early rehearsals for Shadowlands.

HEATHER NEILL: You began writing when you were very young, didn't you? A novel at 15?

WILLIAM NICHOLSON: It sounds grander than it is, but I was so excited by the idea of writing – of inventing – and I was reading a lot of James Bond at the time, so I thought I would write a Bond-style book. The research – guns, cars, what kind of villain – it was like magic. I've never re-read it, but I remember the excitement.

But you always made time for your writing. Didn't you get up to work on a novel for two hours every day before going to the BBC?

Yes: well, other people do it in the evening, but I'm not very good in the evening. When I look back, I wasn't an obviously talented writer, I just wanted to do it. All through my teens I was writing. When people say "How do you get to be a writer?" I say you just have to do a lot of it!

You have a good deal in common with C S Lewis, don't you – apart from working for the BBC?

Do you know, they've pinned up pictures of Lewis in the rehearsal room (pictured below right, Hugh Bonneville, rehearsal images by Manuel Harlan) and I thought, "Oh my God – I've turned into him!" He was bald with a long face and glasses. When I wrote Shadowlands, 35 years ago, I had lots of hair and it never occurred to me that I was anything like Lewis.

But, although it worked out very differently for you, you do share his interest in religion.

But, although it worked out very differently for you, you do share his interest in religion.

Very much so – and I think I share a certain kind of attitude to religion with him. Although he was a believer and I'm not, he was an intelligent believer, very open to arguing his way through things. I used to be a believer, so I understand all of that. I had very strong faith until the age of about 18, until university. One major difference between us is that his mother died when he was young, only nine. And he lived in a different age to me and was emotionally repressed. I was not at all and grew up in an age when people were sexually freer.

You have said Lewis's reluctance to commit was what drew you to him and to writing Shadowlands.

Yes, that was the connection. Lewis had a person die on him and the reluctance to allow yourself to become emotionally dependent on somebody who might die on you – although I never had that – was paralleled with me. I supposed it was because I wanted to be a writer, was doing a double job and just didn't have time for marriage and a family. Looking back, I think that was a cover for the more normal reason: fear of emotional pain, of being dumped. That's why I was able to write about his fears; I had similar fears.

A colleague at the BBC suggested you write a play about Lewis's story. Did you know much about Lewis?

It wasn't my idea at all. I didn't really want to take it on but then, after a bit, I said I'd do it if I could write about love and pain. I was raised a Catholic and Lewis isn't highly thought of among Catholics, more among Protestants, especially in America. During the war he did a series of broadcasts [later published as Mere Christianity], which were very influential. I think his media fame didn't go down well among his Oxford colleagues: they never allowed him to be a serious academic – which he very much was. I soaked myself in his work, but there isn't a single line of CS Lewis in the play – except one: "Pain is God’s megaphone to rouse a deaf world."

The Problem of Pain was one of his most famous books. And you begin with it, don't you?

The play begins with a seven-minute talk about pain, about how a just God could allow suffering, which Lewis argues is to free us from the toys of this world, and allow us to have an understanding of the ultimate reality, which is beyond this world. But, of course, it's a set-up by me. At the beginning of Act II, when Joy is ill, he can't bear it and the same speech starts to crumble. And during the course of Act II he starts unthinking all his thoughts, saying God is a vivisectionist and things like that. That's the theological strand. The emotional one is that he gradually realises that you accept pain because it is the obverse of life and joy and you can't have those without losing them. We all decay and die.

How did you learn about Joy?

There was a biography and letters and she wrote poetry, which I quote in the play. The things she says, for example about her life with her husband Bill Gresham, how he walked out on her, wanted to marry someone else, and how she had a religious experience, come directly from her.

And the intellectual and gossipy banter between the dons?

I made that up! You sort of feel a character and then they start to talk and it feels right. I did my best to find out about Lewis's life, but those characters are composites. The only one who is an exact version is Warnie, Lewis's brother (pictured below, played by Andrew Havill, centre, with Liz White and Hugh Bonneville). We know quite a lot about him: he had an alcohol problem and an undemonstrative manner. The way Joy speaks to them is all part of trying to get some laughs into the play and even at the most emotional moments there are laughs – but those are made up by me.The act of writing is a sort of empathy. You become each character in turn, feeling the feelings first of Jack, then of Joy – and I've already established her character as a sassy New York Jewish wisecracker so it feels appropriate that she would hide the intensity of emotion behind a jokey surface, even when dying. Then I think, "But how's he going to feel about that?" Joy's son, Douglas, appears in the play. Is he still alive?

Joy's son, Douglas, appears in the play. Is he still alive?

Very much so. There were two boys, but David has never wanted to have anything to do with the CS Lewis circus. I didn't realise that Douglas would still be alive when I wrote the television version, but he surfaced while we were filming it, asked to see the script and he said, "There are some things here you are going to have to change." The key thing was the attic scene, after Joy is dead and the boy Douglas says he doesn't believe in heaven. The real Douglas said, "But I did believe." It didn't work dramatically, so we left it as it was. Douglas saw the final version, unchanged – and he got it. He said, "Nothing you've written about this is true, but it's the truest picture I've ever seen of Joy and Jack" [Jack was Lewis's nickname]. I got him to write it in a letter and we printed it in the programme of the play. He's always supported it strongly ever since. He is a committed Christian to this day – he was baptised at the same time as his mother and that meant a lot to him – and I think it's remarkable that he's supported it.

I often use this story to explain that delicate business, your responsibility to real people when you are writing – as I have done quite often. You can't be legalistic or documentary about it. You could write a play about somebody in which every single line was authenticated, but it could still be a travesty of the truth, because it's all about how you assemble the material. Simple legal footnoting of lines will not give you truth because you are taking the immense complexity of a life – or even of ten years – and reducing it to two hours, so by definition you are distorting everything. You have to take responsibility as the writer for the effect of the new animal you are creating. If it delivers something true to those people in a way they recognise and love, you've done your job. If it doesn't, you've abused them and that's not acceptable. I always let living subjects read the script, listen to what they say and explain why I can't put in all the complications of their lives.

Including Mandela, when you wrote the script for Long Walk to Freedom?

Absolutely. Well, he himself didn't want to read it, but all his people did – and I was happy that they did.

The Narnia books were already published by the time Lewis met Joy and The Magician's Nephew is important in the play in that it allows you to draw the parallel between Lewis and Douglas, who both lost their mothers in childhood.

There was a vogue for children's stories at the time. Lewis's friend Tolkien had created his world long before the Narnia series was published. It was very successful and I think that annoyed Tolkien quite a lot. The books have a power which he perhaps didn't recognise. In The Magician's Nephew, the book that Douglas has, the mother is dying and a magic apple saves her. When Douglas comes to his mother in hospital Lewis feels a fraud because there is no magic apple to cure Joy. I've very strongly wedded the strands together.

You are obviously a literary writer, yet you adapt your own stage scripts for film – Shadowlands and now Hope Gap – which must involve a good deal of cutting. Is that hard?

It's just different. It's true I can't indulge in long, wordy performances on film; it does have to be trimmed back a lot, but I find that fascinating as well. You can do things you can't on stage: go to a different place on a cut, have the choir of Magdalen College singing – and there the whole damn lot are, singing! Your toolbox is in one sense richer, but writing for stage is almost the best because there's something very pure about knowing you are asking the audience to do the work. If the soundtrack produces the sound of rain and the characters put up umbrellas, you are asking the audience to imagine rain falling and we do it immediately. That's magical. All the emphasis then is on performance, which is where the emotion comes from.

How did the film of Shadowlands come about?

I was hired by Columbia to write the screenplay and the director Sydney Pollack – a very brilliant man – came to see me in Sussex and he said, "Get me a subplot." I did that. We had a script in good shape, but he then became unable to do it. The producer got it to Richard Attenborough who loved it, immediately knew exactly how to cast it, and didn't change a word.

You've just adapted another play for the screen, but this time directed as well. How was that – combining the roles?

Wonderful is the answer! I absolutely loved it! I was able to take the play, The Retreat from Moscow, and in turning it into a film script, Hope Gap, solve a lot of problems. I think it's much better because I don't think I really solved the ending in the play, but I do in the film. And, of course, I'm able to have more characters. It's too expensive in theatre, but you can get someone to do one day's filming and it's relatively inexpensive so I could have lots of other characters. We filmed in Seaford, Sussex – where it's set – and Yorkshire. I was in complete control, able to cast it as I wanted and shoot it as I wanted, which is a novel experience for me. And, thank God, I had wonderful actors because, in the end, that's what matters. It's about my parents, played by Annette Bening and Bill Nighy, and Josh O'Connor (pictured below, with Annette Bening © Hope Gap Productions Ltd/Robert Viglasky) is being me. The autobiographical story has gone through the dramtic transformation act. It is not factual, but it roughly follows what happened when my parents' marriage broke down, when I was fully grown up, 27 or 28. It's about what happens when a young man thinks his job is to prop his mother up, gradually realising he's in the mess himself. Do you think this experience was part of the reason for your not wanting to commit to a relationship yourself when you were young?

Do you think this experience was part of the reason for your not wanting to commit to a relationship yourself when you were young?

Yes, I do. My parents' marriage went very badly wrong, but after a long time. They were both good people. There's no villain in this – and that's what I wanted to capture in the film, the story of two honourable, moral, decent people causing each other terrible pain. I understood both of them. I wanted to honour them both, while telling the truth. It's a very painful film, but not by the end – everybody grows, including the boy. We had a very good rehearsal period – unusual for a film – and that helped a great deal.

And the title?

Hope Gap is a geographical feature near Seaford. There's a cove under the cliffs called Hope Gap which features in the film and which I used to go to a lot as a child with my mother. When the tide goes out, there's a great expanse of rock pools and when the tide comes in it comes right to the cliffs so you have to get out. There's a big sign saying: "No exit at high tide".

Why did you start writing for young people?

It was when I got frustrated with the film business, the fact that I had no control over my own work. So I thought I'd go back to writing novels, which I'd done before but none had succeeded. And I asked myself where I'd gone wrong and it seemed to me that I'd tried too much to be a great writer, to write a grand work, and what had come out had been pompous, ponderous and lacked life. I thought – I know, I'll write for children. You can't preach to children. I'll write for the pure joy of storytelling. I'll think up a wonderful plot and have a galloping good time. I'd noticed my own children reading books – they were young then – they never criticised a book, they just stopped reading. So I thought, "Nobody is going to stop reading my book; they'll really want to know what happens next." In The Wind Singer, a fantasy, I intended no depths, no grand ideas and complexities. But as any writer will tell you anything you write comes from you, so of course it's full of my preoccupations about people, life and death. It was published in 2001 and did very well – and still does, with sales pushing a million, and there are two others making up The Wind on Fire trilogy.

You have said that in your adult novels you are drawn to write about the messiness of now.

Yes, I'd like to write about Brexit, but don't know how. I've written a lot of novels about the immediate moment – one, Adventures in Modern Marriage, was set at the time of the 2015 election, not about it, but that's the background. The Secret Intensity of Everyday Life is made up of short chapters, each from the point of view of a character. Some little thing would happen, in the next you'd see the same thing from another point of view and you realise people are misunderstanding each other all the time. This keeps on happening. It's a complex story but nothing important or grand ever happens.

Do you know where your capacity for empathy comes from?

I think, in a way, I'm an interesting combination of both my parents. My father was very intellectual, fascinated by ideas, philosophical and scientific arguments – he was a doctor – and not very good at opening up emotionally, which was one of my mother's problems with him. My mother was extremely open with her emotions and she made me constantly aware of the reality of my emotions. Everything was talked about. My mother could be uncomfortably frank and also very funny. So I was in quite a good position to alternate between these two types when writing Shadowlands. It's why I'm a writer. There is a line in the film (not the play) when Lewis says, "We read to know we are not alone", a much quoted line never said by Lewis. And that's what I do: I read and I write to connect with the experience of people who are not me. That for me is the core of being a writer, being able to recreate what's actually happening inside other people. The writers I admire most are of that type, like Tolstoy or Proust, who are extraordinary in their insight. And that's what I try to do myself. I ask a lot of questions and learn a lot. I'm not the greatest of writers but I know why I'm doing it and I know, when I'm doing it, when I've got there!

- Shadowlands runs at Chichester Festival Theatre until May 25

- Hope Gap will be released in the UK later this year

Add comment