There are obvious reasons why films about the theatre outnumber plays about the movie industry, but here’s a play that bucks that trend. Anthony Neilson’s latest drama is located on a film set somewhere distant, hot and challenging but doesn’t allow us so much as a peep at the local colour. Throughout the evening any potential view of the wider world is blocked on stage by those wheelie screens cinematographers use for bouncing light around. Their presence signals the theme of the play.

Unreachable has no interest in glamourising the film industry. Instead, it sets out to satirise the creative process and show how perfectionism can tip over into toxic self-regard, unleashing mayhem among cast and crew. The tone is one of savage comedy, and you might guess that professional experience has informed the material at some level, for Neilson (who also directs this production) is a playwright known for living dangerously. Once described by The Arts Desk as "the wild man of new writing", his process is to devise his plays during the rehearsal period with heavy input from the cast. Thus the finished version emerges only (and if he’s lucky) on press night, with no chance of publishing the final text. The lurching dynamics of the performance I saw are witness to this seat-of-the-pants method. There’s still time for the play to settle, but it’s unlikely that smooth, conventional drama was ever the aim in view.

The tone is one of savage comedy, and you might guess that professional experience has informed the material at some level, for Neilson (who also directs this production) is a playwright known for living dangerously. Once described by The Arts Desk as "the wild man of new writing", his process is to devise his plays during the rehearsal period with heavy input from the cast. Thus the finished version emerges only (and if he’s lucky) on press night, with no chance of publishing the final text. The lurching dynamics of the performance I saw are witness to this seat-of-the-pants method. There’s still time for the play to settle, but it’s unlikely that smooth, conventional drama was ever the aim in view.

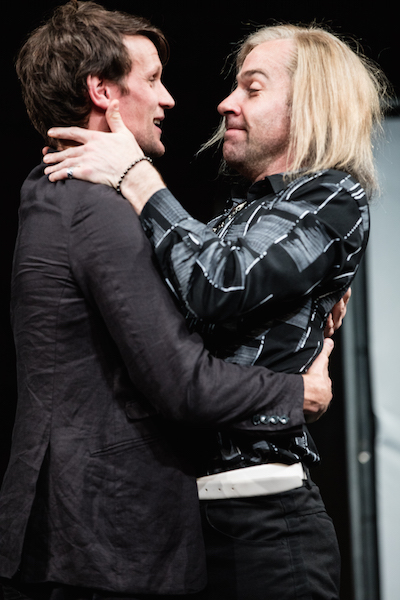

In his first stage outing since American Psycho, Matt Smith (pictured below, with Jonjo O'Neill) brings a scowling and slightly mumbling introversion to Max, a talented but tormented young film director for whom winning the Palme d’Or at Cannes has only increased his anxiety levels. “Any moron can make pretty pictures,” he says, in answer to the motherly brow-stroking of his producer, Anastasia (excellent Amanda Drew, pictured above). She is one of several characters on whom Max makes outrageous demands and who just keep rolling with the punches, partly because they really believe in him, but increasingly, the play suggests, because they’re scared to break out of the isolating bubble of the film set and face the real world.

Max is also the nemesis of pragmatic Carl (Richard Pyros), his director of photography. Mid-shoot, Max demands a switch from digital to old-fashioned film, forcing yet another long hiatus on a schedule already weeks behind owing to his insistence on shooting only at dawn and dusk. He has become obsessed with capturing a certain quality of light, a light that “suddenly hits you with a wave of emotion”, but it’s soon clear that this is a chimera, and his fevered search for it an unconscious delaying tactic. Max’s biggest terror, in truth, is completing the film.

Max is also the nemesis of pragmatic Carl (Richard Pyros), his director of photography. Mid-shoot, Max demands a switch from digital to old-fashioned film, forcing yet another long hiatus on a schedule already weeks behind owing to his insistence on shooting only at dawn and dusk. He has become obsessed with capturing a certain quality of light, a light that “suddenly hits you with a wave of emotion”, but it’s soon clear that this is a chimera, and his fevered search for it an unconscious delaying tactic. Max’s biggest terror, in truth, is completing the film.

Max decides that its problems can be solved by replacing a key actor. Cue the arrival of Ivan, aka The Brute, a Balkan bottle blond in tight trousers and medallion, whose reputation for explosive stroppiness goes before him. Clearly inspired by Klaus Kinski, crossed with the preening ludicrousness of Meatloaf, Jonjo O’Neill’s Ivan (pictured above, with Smith) not only generates the biggest laughs of the evening, but threatens to tip the play into expletive-laden farce (and what imaginative expletives they are). His physicality peps things up, too. There is a very funny send-up of masculine reserve when Max is chased around the set by the new arrival who merely wants to give him an affectionate kiss.

Overall, though, too many of the narrative strands lack focus, and we are offered too few glimpses into the characters’ inner lives to render them sympathetic. Tamara Lawrence makes the most of what the script offers as the film’s young black star, at first startlingly forthright but increasingly willing to put aside her principles as she falls under the director’s blighted spell. Drew also touches a nerve in her portrayal of a producer who has sacrificed so much for her job that she has no real feelings left. Faced with a need to relax, she’ll have sex with Carl or a chamomile tea – she doesn’t mind which, as long as it does the job.

One by one, the play demolishes an entire skittle-alley of creative industry myths. When the director presses his young star to reveal why it is that she is able to give such a moving performance in her role in his film, believing that she must be drawing on “personal buried pain”, her scorn is palpable. “I’m an actress. If you want me to feel something, pay me.”

- Unreachable at the Royal Court to August 6

- Read more theatre reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment