Minimalist sculpture has, for decades, been making gallery visitors self-conscious. How should you react to a metallic piece by Donald Judd which has evidently been machined rather than modelled? Can you really walk all over an arrangement of lead floor tiles by Carl Andre? And how do you look at a Robert Morris mirrored cube without seeing yourself gazing back?

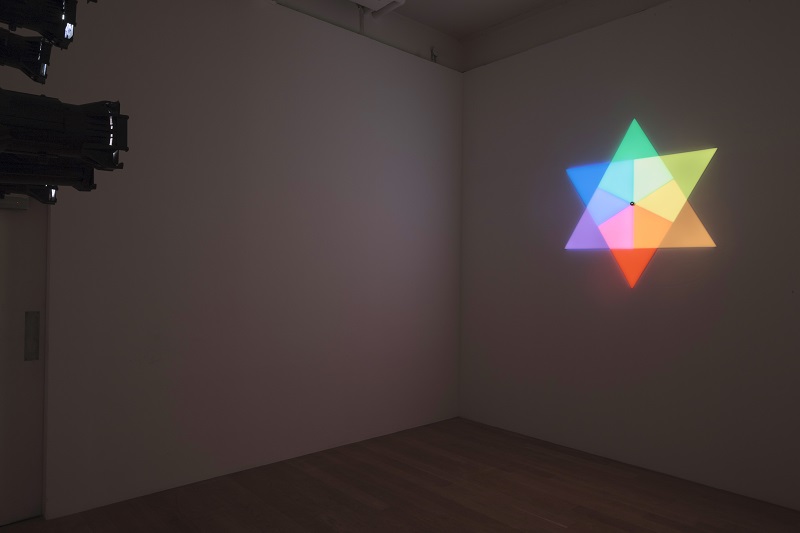

If you’ve ever worried about questions like these, the show at Fruitmarket could offer some relief. It promises an alternative minimalism, not from intellectual, uptight New York, but from America’s laid back West Coast. And it invites you to consider works in which raw materiality gives way to airiness and natural light: this minimalism is easier to enjoy (Pictured below: Jeppe Hein Geometric Mirrors II, 2010 and Olafur Eliasson The Colour Spectrum Series, 2005).

Two pieces here act as touchstones. Downstairs a moonlike acrylic disc is lit by four spots. Robert Irwin’s installation hovers about a foot from the wall and the dancing shadows encourage us to move around and play with its shifting appearance. As curator Melissa Feldman argues, the experiential nature of these works has never been more timely: we live in an age of participatory art.

Larry Bell is the other veteran artist to demonstrate a twist on minimalism. His mirrored cubes are altogether more mysterious than anything thrown up by the mainstream movement. Constructed with coloured glass coated with a nickel alloy, their smoky finish hints at occult properties. As the sort of mirror Jorge Luis Borges might have written a story about, this too invites you to consider your own metaphysical location.

Larry Bell is the other veteran artist to demonstrate a twist on minimalism. His mirrored cubes are altogether more mysterious than anything thrown up by the mainstream movement. Constructed with coloured glass coated with a nickel alloy, their smoky finish hints at occult properties. As the sort of mirror Jorge Luis Borges might have written a story about, this too invites you to consider your own metaphysical location.

The Californians aptly called their movement Light and Space, but artists such as Bell and Irwin have largely flown under the radar of critical attention. It is only in recent years that exhibitions at MoCA in San Diego, David Zwirner in New York and also White Cube in London and Miami, have begun to put Light and Space back on the map.

Perhaps this show makes the boldest claims yet for the West Coast minimalists. Curator Feldman points out that Bell and Irwin have both influenced at least ten important younger artists, including Olafur Eliasson, Tacita Dean, Spencer Finch and Ann Veronica Janssen. Indeed, Eliasson’s The Weather Project, 2003, an indoor sun installed in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, can be seen as squarely in the tradition of Light and Space.

The Dane is represented here in Edinburgh by a colourful projection of a moving tangram puzzle, which really does leave you scratching your head (Pictured below left: Olafur Eliasson, Ephemeral Afterimage Star, 2008). The sequence is unpredictable, but the bright colour, when it saturates the screening area, is thrilling and just as unexpected. Works like this repay patience, but that’s another quality which this show sets out to foster.

You will certainly have to slow down for the film by Tacita Dean, in which we encounter a lighthouse in the North East of England. Dean shoots her film wide-angle and this adds drama to the sweep of the anachronistic flashlight. Watching the rotation of mirrors, bulbs and lenses one might consider the sculptural aspect of the building. At other times, the viewer sees nothing and, plunged into darkness, begins to crave the return of the light.

Without light there could be no film, no photography, no vision. But of course at times darkness is also the subject of art. American artist Spencer Finch explores shade with a set of seven coloured fluorescent tubes that relate to shadowy photographs by Eugène Atget. Atget was working in Paris in the early 20th century and Finch has translated the light and shadow of his photographs into bands of glowing, candy-like colours.

Without light there could be no film, no photography, no vision. But of course at times darkness is also the subject of art. American artist Spencer Finch explores shade with a set of seven coloured fluorescent tubes that relate to shadowy photographs by Eugène Atget. Atget was working in Paris in the early 20th century and Finch has translated the light and shadow of his photographs into bands of glowing, candy-like colours.

James Welling is another American who approaches light from a cultural reference point. Architect Philip Johnson’s famous Glass House is his minimal, modernist icon. But Welling shoots and films it with a range of coloured filters and he’s not afraid to overexpose the much photographed house, or to allow lens flare. The structure itself might be a paragon of aesthetic rigour but in Welling’s treatment of it, the senses are deranged by the unruly sunlight.

There is, however, a showstopper here in Edinburgh. Ann Veronica Janssens has created the most experiential piece of all using seven acid coloured lights and a roomful of artificial mist (Main picture). The piece is called Yellow Rose and it appears to breathe and flutter from the moment we apprehend it. Get too close to the flower and it disappears: the simple pleasure of seeing a rose is magnified and turned into a piece of relational art.

Yellow Rose remains forever out of reach. Like the rest of the work here it has an effect that is hard to pin down. Contrast that with the controversial “pile of bricks” purchased by Tate in 1976: perhaps Carl Andre’s work was just too sober and literal for a British public with an appetite for spectacle and illusion. As this show ably demonstrates, it could all have been so different.

- Another Minimalism: Art After California Light and Space at The Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh until 21 February 2016

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment