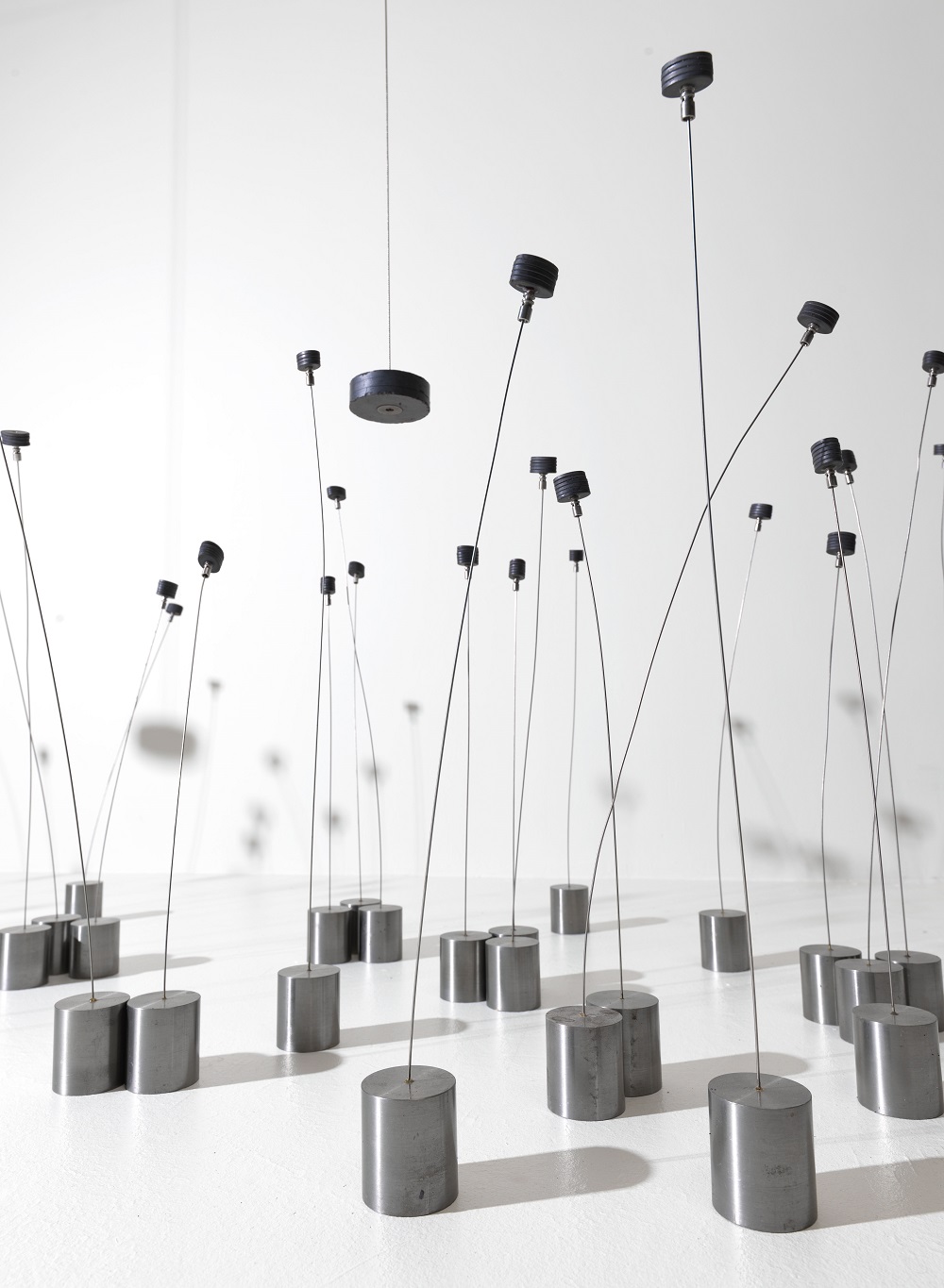

Half organic, half high-tech, a bank of magnet-flowers sways not in response to a breeze, but to a magnetic field. Their uncannily naturalistic movements are coupled with a form that is blatantly functional: an unseen, elemental force masquerades as nature at its most benignly pastoral (Pictured below right: Magnetic Fields, l969). For Takis (real name: Panayiotis Vassilakis), magnetism introduces an extra dimension to sculpture, providing an active component that serves both as material and means. No longer restricted to the mere representation of action, for Takis, sculptures are action.

In his hands, painting too becomes a contested area: canvases bulge as magnets on either side of a painted surface hold a series of abstract objects aloft, as in Magnetic Wall 9 (Red), 1961 (Main picture). It’s a work that both defies and affirms the limitations of two dimensional representation, as objects floating in front of the canvas animate the picture plane, and declare it redundant.

Born in Athens in 1925, Takis moved to Paris in 1954, joining the avant-garde circle based at the Beat Hotel, where he met artists and poets including William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg. The radical possibilities of Takis’s new art were first revealed in 1960 when five months before the first man in space, Takis used electromagnetism to suspend the poet Sinclair Beiles in mid-air. From here, Beiles read his Magnetic Manifesto, in an action that, at the height of the space race, was as politically charged as it was artistic.

Born in Athens in 1925, Takis moved to Paris in 1954, joining the avant-garde circle based at the Beat Hotel, where he met artists and poets including William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg. The radical possibilities of Takis’s new art were first revealed in 1960 when five months before the first man in space, Takis used electromagnetism to suspend the poet Sinclair Beiles in mid-air. From here, Beiles read his Magnetic Manifesto, in an action that, at the height of the space race, was as politically charged as it was artistic.

In the magnetic sculptures, basic principles are set adrift as the spaces between objects become loaded with significance, teeming with unseen energy as objects connect and communicate with each other. Throughout his career, Takis produced sculptures that look like aerials or antenna, and those that predate his experiments with magnetism in the 1950s look to ancient sculptural forms as a means of accessing some fundamental, primal force.

His sound sculptures are the most beguiling, their eery resonances echoing age-old cries into the void as humans have sought to reach beyond the confines of the known world. Pulses of electromagnetism pull rods against wires in a series of Musicals from the mid-1960s: stuttered, but pure sounds emerge. They sound as if they have been revealed, not made, by devices that are less musical instruments than scientific ones, transmitting the sounds of the cosmos itself. The language is all amusingly hippyish, but as today's sound artists continue to pick over roughly the same territory, the significance of Takis's project is less easily dated.

- Takis: Sculptor of Magnetism, Light and Sound at Tate Modern until 27 October 2019

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment