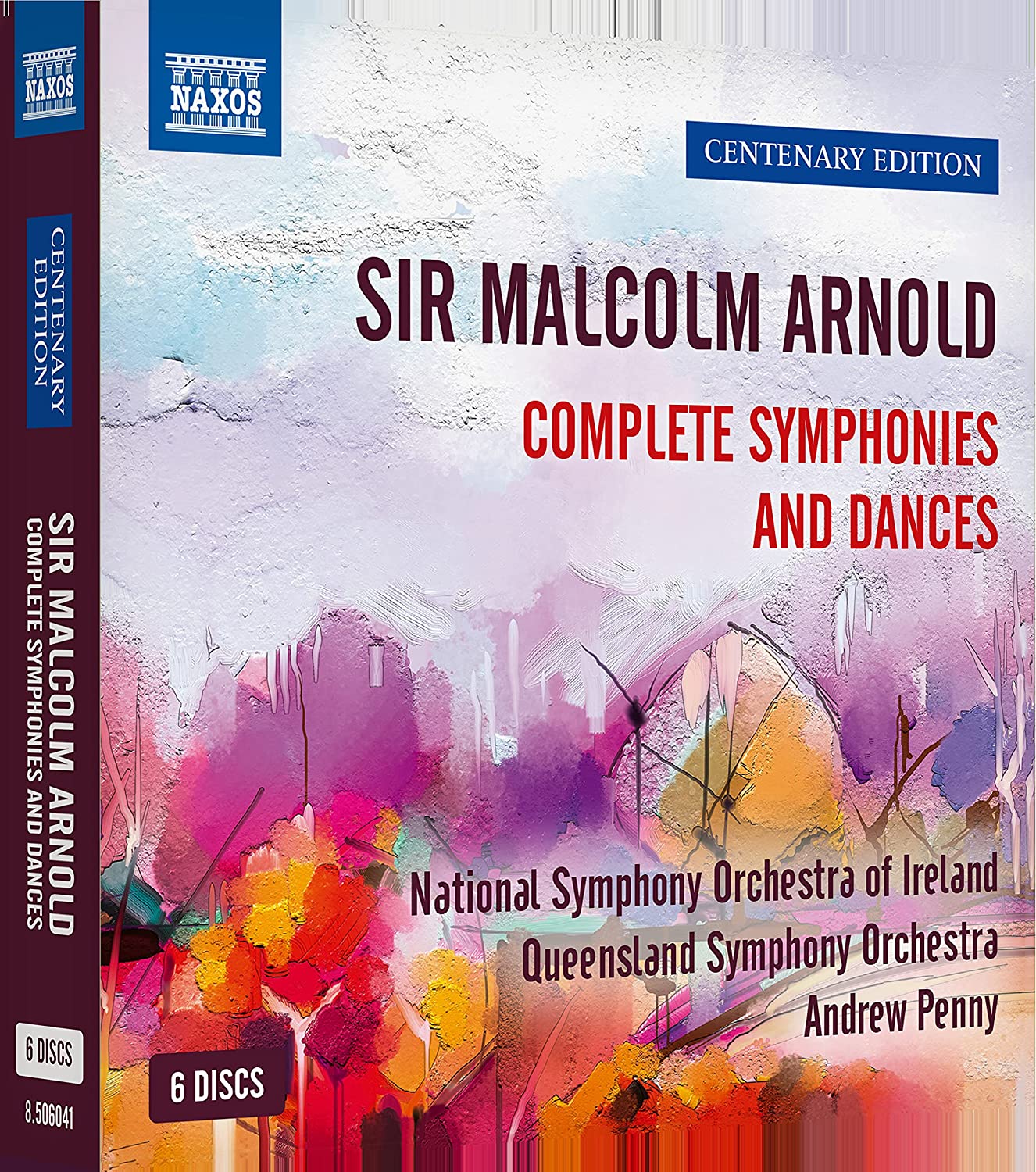

Malcolm Arnold: Complete Symphonies and Dances National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland, Queensland Symphony Orchestra/Andrew Penny (Naxos)

Malcolm Arnold: Complete Symphonies and Dances National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland, Queensland Symphony Orchestra/Andrew Penny (Naxos)

Working through these nine symphonies in chronological order is a fascinating and disturbing experience, the giddy peaks and deep troughs of Sir Malcolm Arnold’s personal life mirrored in sound. If you’ve only ever encountered Arnold’s lighter output, you’re in for a surprise. There’s plenty of sardonic humour and a lengthy string of improbably memorable tunes, but the prevailing impression is one of deep seriousness. Arnold often wrote for large forces, but he was a master orchestrator: even at his most bombastic, the textures remain clear and bright. Composed between 1947 and 1986, these works span the composer’s career, the stark counterpoint which opens Symphony No. 1 revisited in the 9th. Andrew Penny’s Dublin recordings played a useful role in rehabilitating Arnold’s reputation in the late 1990s, and it’s good to hear them again, attractively repackaged at budget price to commemorate the composer’s centenary year. There’s a winning freshness to these performances, the all-important wind, brass and percussion writing ideally present.

Symphony No. 1 makes for a startling debut, strikingly scored and full of wide, open spaces, the clouds only lifting in the finale’s technicolour coda. No. 2 is a delight; if you want proof of Arnold’s compositional prowess, listen to the build up to the first movement’s recapitulation, one of my favourite moments in any 20th century symphony. There’s a haunting slow movement too, one of many allusions to Mahler. Symphony No. 3’s quick outer movements are a lot darker than they initially seem, surrounding a very elegiac Lento. Still more disconcerting is its successor, No. 4’s first movement containing one of the greatest tunes Arnold penned, a syncopated bass line preventing things from feeling too smooth. The finale’s fugue unfolds with incredible assurance, the movement almost toppling into the abyss when a marching band appears. Penny’s brass are fearless. Play this disc at high volume.

Symphony No. 1 makes for a startling debut, strikingly scored and full of wide, open spaces, the clouds only lifting in the finale’s technicolour coda. No. 2 is a delight; if you want proof of Arnold’s compositional prowess, listen to the build up to the first movement’s recapitulation, one of my favourite moments in any 20th century symphony. There’s a haunting slow movement too, one of many allusions to Mahler. Symphony No. 3’s quick outer movements are a lot darker than they initially seem, surrounding a very elegiac Lento. Still more disconcerting is its successor, No. 4’s first movement containing one of the greatest tunes Arnold penned, a syncopated bass line preventing things from feeling too smooth. The finale’s fugue unfolds with incredible assurance, the movement almost toppling into the abyss when a marching band appears. Penny’s brass are fearless. Play this disc at high volume.

Arnold’s reputation took a hit after the 1961 first performance of his Fifth Symphony, described by one critic as a 'portrait of an artist in a visible state of disintegration.' What tosh. This is an extraordinarily eloquent work and an excellent starting point, the first movement paying tribute to several of Arnold’s recently deceased friends, including horn player Dennis Brain and humourist Gerard Hoffnung. What still shocks is the finale’s close, Arnold bringing back the slow movement’s glowing big tune before abruptly switching off the lights. It’s unbelievably bleak. Perhaps Penny’s last movement could do with a touch more bite, but the rest is superb. No. 6 is more uncompromising, the major key coda deliberately hollow-sounding, and No. 7 is bleaker still, its three movements allegedly portraying Arnold’s three children. I love the first movement’s noir-ish second subject, and the E flat clarinet’s shrill, ragtime variant, complete with leery trombone solo. The cowbell on this recording is indecently loud, as it should be.

Arnold’s reputation took a hit after the 1961 first performance of his Fifth Symphony, described by one critic as a 'portrait of an artist in a visible state of disintegration.' What tosh. This is an extraordinarily eloquent work and an excellent starting point, the first movement paying tribute to several of Arnold’s recently deceased friends, including horn player Dennis Brain and humourist Gerard Hoffnung. What still shocks is the finale’s close, Arnold bringing back the slow movement’s glowing big tune before abruptly switching off the lights. It’s unbelievably bleak. Perhaps Penny’s last movement could do with a touch more bite, but the rest is superb. No. 6 is more uncompromising, the major key coda deliberately hollow-sounding, and No. 7 is bleaker still, its three movements allegedly portraying Arnold’s three children. I love the first movement’s noir-ish second subject, and the E flat clarinet’s shrill, ragtime variant, complete with leery trombone solo. The cowbell on this recording is indecently loud, as it should be.

That the Eighth Symphony is so cogent is remarkable, given Arnold’s sharply declining physical and mental health in the late 1970s. This 25-minute work is a brilliant, punchy last gasp, the finale not a million miles from the popular dances with which Arnold made his name in the 1950s and 60s. The slow movement should move sensitive listeners to tears. After which, things get a bit sticky. No. 9, composed in 1986 after the composer had, in his own words, “been through hell”, is extremely hard going, the long, slow finale difficult to digest. Penny acknowledges in the notes that the symphony is biographically important, but it makes for bleak listening, as do the late Welsh Dances from 1988. Whether these late works should have been published at all is a moot point. While they certainly don’t enhance Arnold’s reputation, one’s glad that they exist at all. If you’re curious to learn more about Arnold’s troubled life, track down the biography by Anthony Meredith and Paul Harris, an unflinching, entertaining and affectionate portrayal of one of the great 20th century British composers. Penny’s Queensland Symphony Orchestra recording of the complete English, Scottish, Cornish, Irish and Welsh Dances is thrown in as a bonus, reverberantly recorded but sweetly played. An essential acquisition.

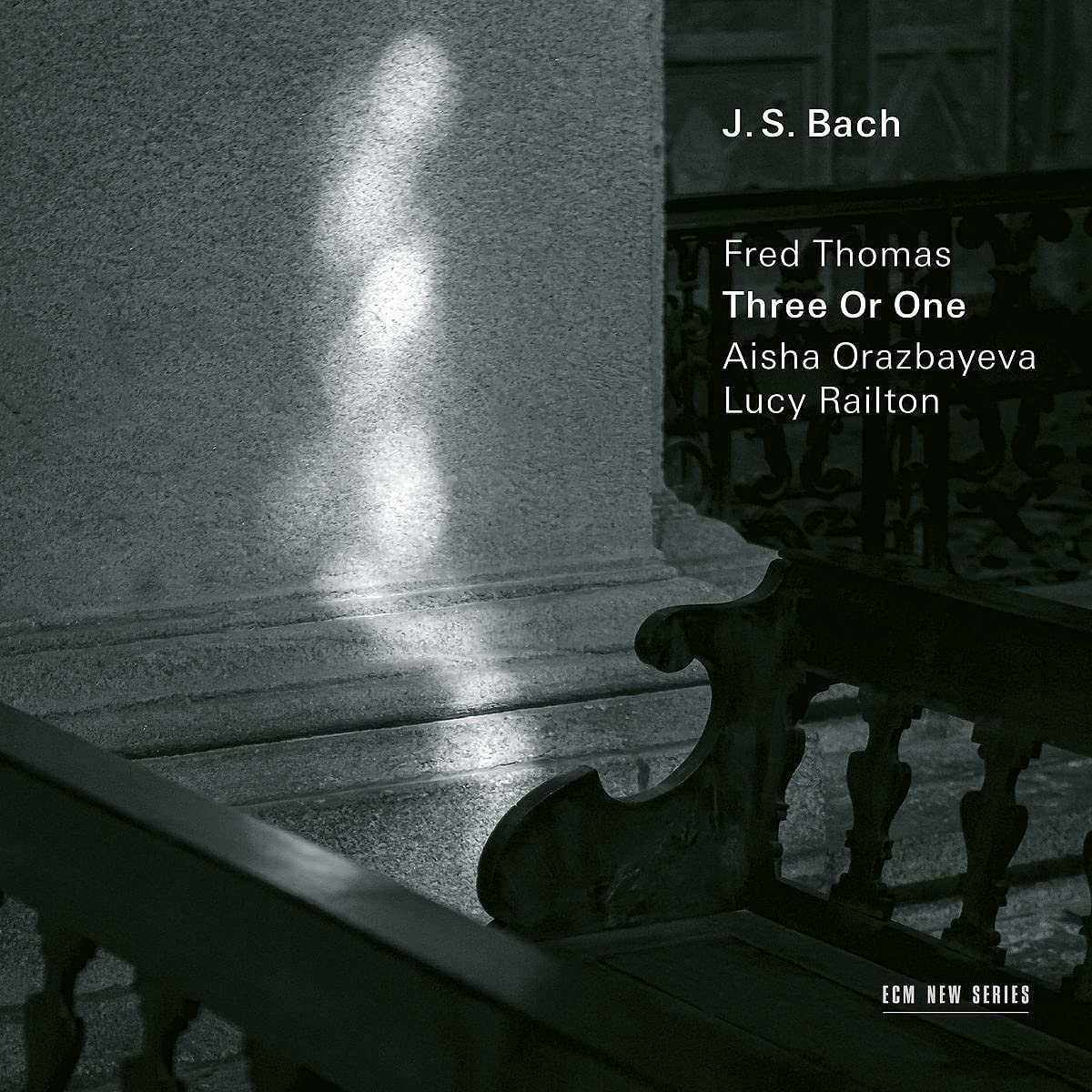

JS Bach/ Fred Thomas: Three Or One Fred Thomas (piano), Aisha Orazbayeva (violin), Lucy Railton (cello) (ECM)

JS Bach/ Fred Thomas: Three Or One Fred Thomas (piano), Aisha Orazbayeva (violin), Lucy Railton (cello) (ECM)

Hm. 24 transcriptions of J.S. Bach, some for a trio of piano/violin/cello, the rest for solo piano. There are bound to be some people repelled by the mere idea of it. I can hear spluttering over Historically Informed Muesli, and as for people who like to keep their classical record collections in neat sequence, where on earth are they going to put it? Both opinions would be wrong: this is a deeply felt and beautifully recorded album of re-imagined short Bach pieces which have been “threaded into a compelling sequence” by Manfred Eicher. Pianist and arranger Fred Thomas, making his debut as leader on ECM, is an astonishingly fine musician, and his string colleagues - Kazakh violinist Aisha Orazbayeva and English cellist Lucy Railton - understand and support his many-faceted vision brilliantly, fitting empathetically into a multitude of varied roles.

Fred Thomas explains what interests him: to “separate the voices and avoid the typical blending and blurring of the organ in a church [..] to illuminate how the musical characters interact, sometimes stubbornly ignoring one another as they continue their trajectories...” One gets a feel for that in the aria “Wie zittern” from Cantata 'Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht mit deinem Knecht' in which the two interweaving melodic parts, originally for soprano and oboe, are audio-separated. It’s gorgeous. Most of the pieces are either transcriptions of organ chorale preludes, vocal cantata movements or orchestral sinfonias. No track exceeds five minutes; indeed, most of them come in at under two-and-a-half. 'Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein' (BWV Anh. 2/ 78) is just the briefest of vignettes. Orazbayeva’s vibrato-less violin is eerily recessed in the mix. She states the top line of the chorale melody once, against Thomas’s darkly chromatic left-hand piano ruminations. It is very short but highly effective, and deeply affecting.

Sebastian Scotney

Brahms: String Quartets 1 and 2, String Quintet No. 2 Dudok Quartet, with Lilli Maijala (viola) (Rubicon)

Brahms: String Quartets 1 and 2, String Quintet No. 2 Dudok Quartet, with Lilli Maijala (viola) (Rubicon)

Brahms is a quintessentially autumnal composer: think full textures and plenty of wise, consolatory words. There’s plenty of hygge in this new set of string quartets from Amsterdam’s Dudok Quartet, the sound softer and gentler than we’re used to, these beautifully poised performances recorded with gut strings. Violinist Judith van Driel and cellist David Faber talk about embracing 19th century performance practice and recreating the works as Brahms might have heard them in their sleeve note, but nothing feels mannered. Rubato is sensitive, and portamento discreet; the overwhelming impression is one of warmth, this Brahms smilier and cuddlier than some performances suggest. Quartet No. 1’s hushed opening is superbly done, and the rhetorical chords which follow it pose questions rather than bludgeoning us. The interplay between the two violins is sweetly handled, especially when heard through headphones. I like the finale’s driving energy, the C minor close exhilarating rather than depressing. No. 2, composed at the same time, follows a similar template, these players at home in the slow movement’s ear-worm of a main theme as they are in the minuet’s skittish trio.

Quartet No. 3’s creation was a smoother process, Brahms dedicating the work to a doctor friend and telling him that “It’s no longer a question of a forceps delivery; but of simply standing by.” Sunnier and more relaxed in mood, this gets another idiomatic reading. The Andante sings and the last movement’s variation sequence flows sweetly. As a filler, there’s the String Quintet No. 2, originally intended by Brahms to be his last work work. You can’t imagine a better way to bow out, but Brahms couldn’t kick the habit and composed the clarinet sonatas and a few piano pieces. Violist Lilli Maijala joins the Dudoks in a performance that’s comparable to a slice of rich fruit cake, one where the flavours aren’t subsumed by excess starch or sugar. It’s glorious, especially in the genial finale.

- Brahms on Amazon

- Judith van Driel of the Dudok Quartet Amsterdam writes about the challenges of Brahms

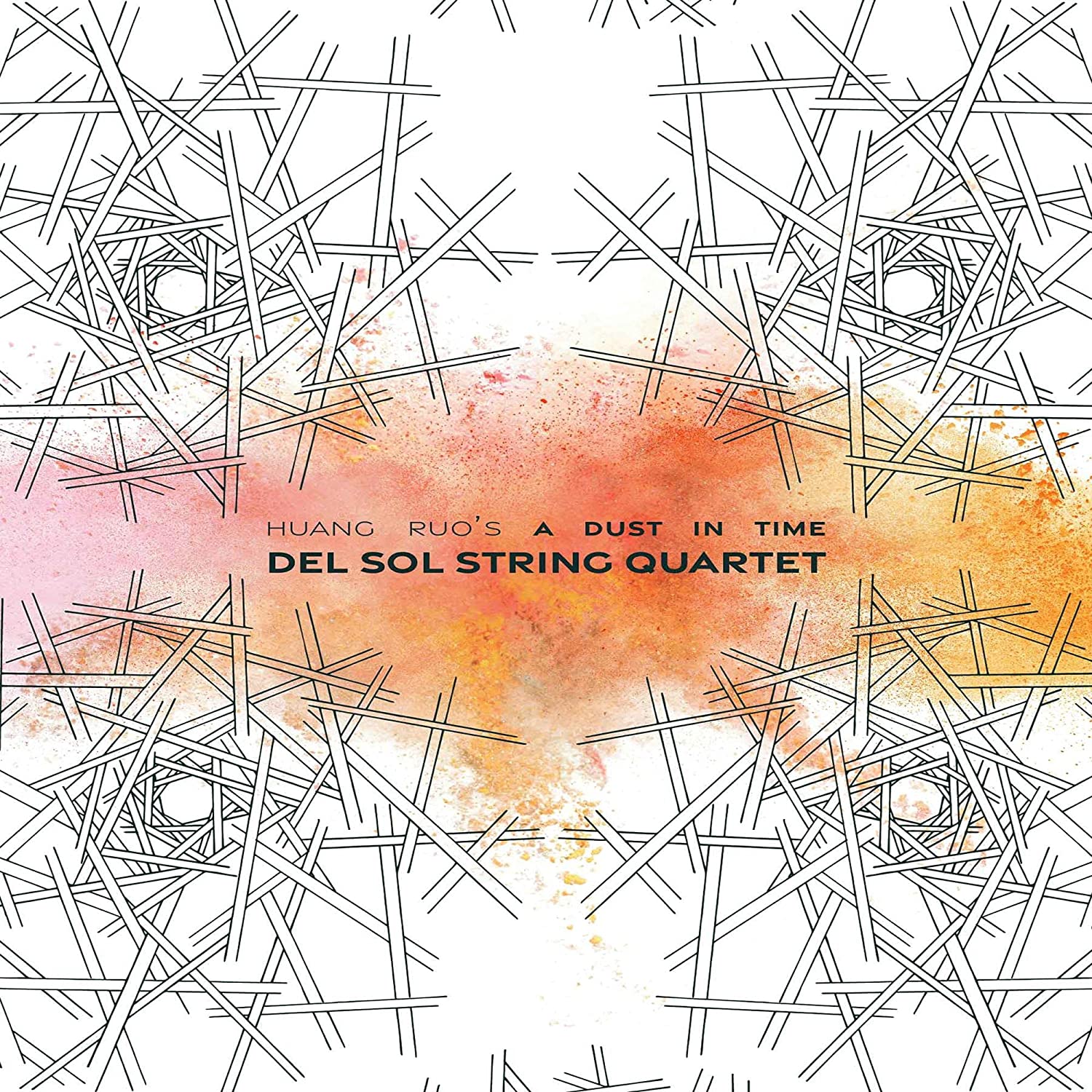

Huang Ruo: A Dust in Time Del Sol Quartet (Bright Shiny Things)

Huang Ruo: A Dust in Time Del Sol Quartet (Bright Shiny Things)

Huang Ruo’s movement titles evoke epic spans, but the chronological distances travelled are actually much smaller. A Dust in Time’s 13 movements play out over 60 minutes like a folded sheet of paper: ascending gently towards the “Supereon” then winding down again, its circular form inspired by Tibetan mandala patterns. If you’ve read David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, you’ll enjoy this. Dust is an apt metaphor for the passing of the hours, as anyone who’s spent periods working from home during the last 18 months will realise, Ruo presumably also alluding to our own insignificance in the grand scheme of things.

I listened to A Dust in Time in a single sitting after a very long day and was moved to tears, this serene, radiant music packing a real punch. That the work is so moving is also down to the performance; though recorded over two days, the Del Sol Quartet’s rendition feels like a single take. There’s lots to love about this release before you’ve even inserted the CD. The engineering is impressive, and the physical release comes with a colouring book, its patterns drawn by San Francisco school student Felicia Lee and inspired by Ruo’s music.

The Boulanger Legacy Merel Vercammen (violin) & Dina Ivanova (piano) (TRPTK)

The Boulanger Legacy Merel Vercammen (violin) & Dina Ivanova (piano) (TRPTK)

The most influential musical pedagogue of the 20th century, Nadia Boulanger's list of pupils contains an incrediblly diverse list of musicians. She's the direct link between Barenboim and Bacharach, and also taught Copland and Quincy Jones. Boulanger's gift was for sensing each student's individual character and talent. A workaholic who taught for six days a week, she shrewdly differentiated between her students. The less talented ones were typically let go with a diploma after a year, while the more serious were given a harder tine. Michel Legrand recalled that "good pupils never got a reward so they stayed. I was there for seven years. And I never obtained a first prize!" This compilation celebrates the Boulanger sisters; Nadia's younger sister Lilli was an even more talented composer, winning First Prize in the 1913 Prix de Rome (Nadia had been awarded the Second Prize in 1908), Lilli having dedicated her prize-winning cantata to her older sister as a gesture of gratitude. Lilli died in 1918, aged just 24 and several of her shorter works are included in this violin and piano recital. The "Nocturne" and "Cortège" are exquisite miniatures, originally composed for flute and piano. More striking still is D'un matin de printemps, music of striking assurance and refinement which has sent me down the YouTube rabbit hole in search of more.

Violinist Merel Vercammen and pianist Dina Ivanova also include three pieces by celebrated pupils of Nadia. Grażyna Bacewicz's Violin Sonata No. 3 oozes glittering self-assurance, the language highly personal while sounding ineffably French. Leonard Bernstein remained close to Nadia throughout her life and wasd one of the last musicians to speak with her before her death in 1979. His Violin Sonata was composed in 1939, shortly before he began studying with her. A striking set of variations, the keen-eared will recognise a melody later recycled in Bernstein's Symphony No. 2. Astor Piazzolla approached Nadia hoping to become a cerebral modernist in the post-war European tradition, but she recognised that his voice was best expressed in the writing of tangos. Le Grand Tango was written in 1982 for Rostropovich, and sounds totally idiomatic in Sofia Gubaidulina's violin transcription. The disc ends with a miniature by Nadia herself. The "Modéré", arranged from her 1914 Three Pieces for Cello and Piano, is a jewel, its long-breathed melody unwinding over a rippling piano accompaniment. A terrific collection, superbly played and recorded, and with wittily appropriate artwork.

Add comment