Nikolai Lugansky / Pavel Kolesnikov, Wigmore Hall review - lucidity and depth from two master pianists | reviews, news & interviews

Nikolai Lugansky / Pavel Kolesnikov, Wigmore Hall review - lucidity and depth from two master pianists

Nikolai Lugansky / Pavel Kolesnikov, Wigmore Hall review - lucidity and depth from two master pianists

Schumann and Debussy link two superb recitals, but the connections go much deeper

Reaching for philosophical terms seems appropriate enough for two deep thinkers among Russian pianists (strictly speaking, Kolesnikov is Siberian-born, London-based).

Their approaches to programming were different, but equally assured and individual. While Kolesnikov assembled an interlinked first half of 13 major miniatures – the future of imaginative recital planning, much favoured by twentysomethings – Lugansky’s Part 2 gave us 13 of the colossally demanding sound-worlds that are the Rachmaninov Preludes: not the entire Op. 32 set, with which he stunned an audience in 2014, but an equally plausible sequence starting with six from Op. 23. This is, no doubt, the major Rachmaninov interpreter of our time, running the gamut of expression in these revolutionary dramas. It's only right that there should be a recorded document (pictured below), but the live experience will always have the edge.

As with Debussy’s “Clair de Lune” in the earlier performance of a perfectly poised Suite Bergamasque, there was no chance to swoon over the familiarity of Rachmaninov’s ineffable D major reverie of Op. 23 or its sequel, the charged G minor cavalcade; Lugansky focused both too mesmerisingly to make them comfortable. The massive – and massively underrated – nobility-of-man epilogue to the whole series, the deeply moving chordal sequences of the last, D flat Prelude, showed that Lugansky could go ever deeper while burnishing the sheer colossal beauty of sound, with echoes from No. 2 in that series now closer to hand. Very well, a string of encores had to end with the beginning, the C sharp minor Prelude, but that too was spaciously forged anew, with no sense of giving the audience a familiar leaving-gift.

As with Debussy’s “Clair de Lune” in the earlier performance of a perfectly poised Suite Bergamasque, there was no chance to swoon over the familiarity of Rachmaninov’s ineffable D major reverie of Op. 23 or its sequel, the charged G minor cavalcade; Lugansky focused both too mesmerisingly to make them comfortable. The massive – and massively underrated – nobility-of-man epilogue to the whole series, the deeply moving chordal sequences of the last, D flat Prelude, showed that Lugansky could go ever deeper while burnishing the sheer colossal beauty of sound, with echoes from No. 2 in that series now closer to hand. Very well, a string of encores had to end with the beginning, the C sharp minor Prelude, but that too was spaciously forged anew, with no sense of giving the audience a familiar leaving-gift.

You can also tell a great artist by the way he or she highlights the finish, in both senses, of a shorter piece. Rachmaninov gives ample opportunity in his quirky codas with their surprising delays of the last cadence; Debussy’s Children’s Corner does the same with seeming simplicity, and Kolesnikov wrought each of those afresh with teasing but clear suspensions. The most radical rethink of the two recitals was perhaps Lugansky’s weighty Schumann Kinderszenen, its instant thoughtful spaciousness justified by the painful nostalgia of the closing sequence.

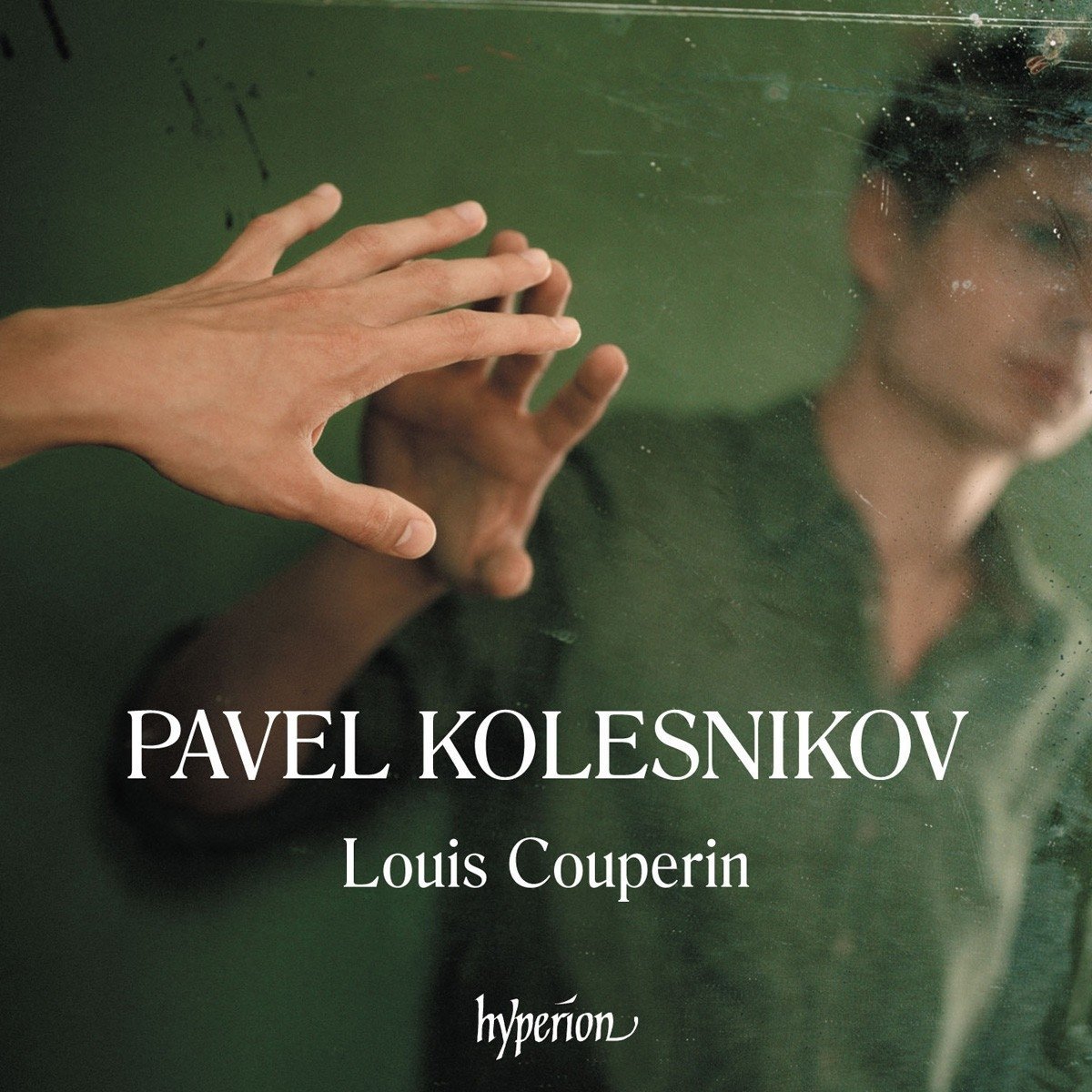

Kolesnikov faced the more elaborate stream of consciousness in Schumann’s mighty Fantaisie by shedding light on every turn, but never robbing the argument of its mystery. Following straight on from the quirky fundamentals of Louis Couperin’s Tombeau de M de Blancrocher – a silver sliver from Kolesnikov’s magnificent assemblage on his typically revelatory third CD (pictured below), in a completely different and crucial context – it was as if his Schumann retreated to be refreshed by clear, introspective springs in order to step nobly back into the limelight. The wonder of the final Adagio has never sounded more supernaturally beautiful.

What encore could possibly follow? Kolesnikov chose to return to the near-beginning with more C major to refresh his Schumann – Debussy’s exquisite homage to Clementi’s studies in the first of his Children’s Corner pieces, “Dr Gradus ad Parnassum”. Maybe it sounded sufficiently different from the performance in the first half for two of my colleagues to ask what it was. Debussy’s measured “children’s games” could hold their own in a parade of fantastical characters, with teasing links to one of Chopin’s typically radical Mazurkas, Op. 30 No. 4 in C sharp minor with its dizzying chromatic descent, and his F minor Etude – cunningly twinned with “The Snow Is Dancing” – Bach’s C sharp Prelude, and two minimalist spellbinders from maverick Helmut Lachenmann’s Ein Kinderspiel.

What encore could possibly follow? Kolesnikov chose to return to the near-beginning with more C major to refresh his Schumann – Debussy’s exquisite homage to Clementi’s studies in the first of his Children’s Corner pieces, “Dr Gradus ad Parnassum”. Maybe it sounded sufficiently different from the performance in the first half for two of my colleagues to ask what it was. Debussy’s measured “children’s games” could hold their own in a parade of fantastical characters, with teasing links to one of Chopin’s typically radical Mazurkas, Op. 30 No. 4 in C sharp minor with its dizzying chromatic descent, and his F minor Etude – cunningly twinned with “The Snow Is Dancing” – Bach’s C sharp Prelude, and two minimalist spellbinders from maverick Helmut Lachenmann’s Ein Kinderspiel.

Lachenmann’s set has been magically highlighted by another younger-generation iconoclast, Mei Yi Foo; here we got the weird overtones of hammered rhythms at the very top of the register in “Schattentanz” – played twice, once to kick off the carnival, later to connect to Liszt’s “La campanella” as you never heard it before – and the chord clusters, with sustaining-pedal overhang, of “Filter-Schaukel”, connecting with the more unpredictable chromatic giddiness of Debussy’s "Feux d’artifice" from Préludes Book Two. Having told us that his first-half dramatis personae would appear in a single, uninterrupted act, was it Kolesnikov’s intention to make a clean break for applause between “Golliwogg’s Cake-Walk” and the last two mould-breakers? Suffice it to say it made sense, like everything in this astonishing programme. The future is bright with phenomenal artists like Kolesnikov around.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

Add comment