Stikhina, Kowaljow, LSO, Noseda, Barbican review - dramatic songs of death, electrifying dances of life | reviews, news & interviews

Stikhina, Kowaljow, LSO, Noseda, Barbican review - dramatic songs of death, electrifying dances of life

Stikhina, Kowaljow, LSO, Noseda, Barbican review - dramatic songs of death, electrifying dances of life

Blazing Beethoven Seventh follows the darkness of Shostakovich's Fourteenth Symphony

“This symphony comprises 11 songs about death and lasts about one hour,” the conductor Mark Wigglesworth declared before a second New York performance of Shostakovich’s Fourteenth – people had left in droves during the first – only to see a swathe of his audience look anxiously at their watches.

I doubt if anyone in an obviously more receptive and surprisingly youthful Barbican audience did that at any point during Gianandrea Noseda’s interpretation at the Barbican last night, which drew focus from start to finish. So did his Beethoven Seventh after the interval in a daring but triumphant programme. The London Symphony Orchestra is clearly on fire right now.

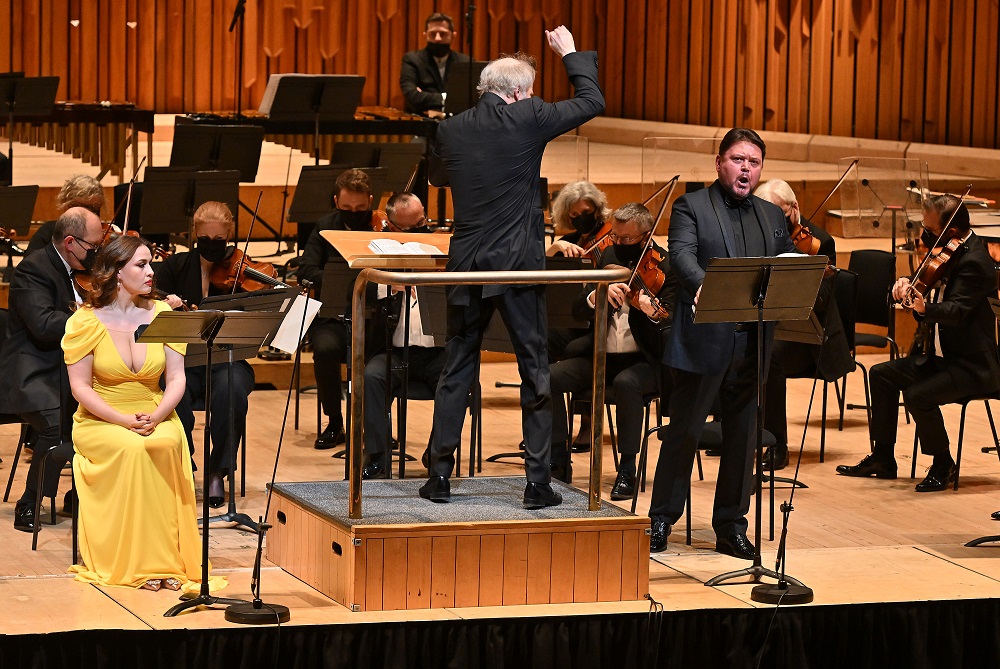

Never has Shostakovich’s song-symphony come more to life as a connected series of contrasted operatic scenes, as if he were still, at the end of his life in the 1970s, channelling the music-theatre more or less forbidden to him after the 1936 attack on Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. I can’t wait to see soprano Elena Stikhina as “the Lady”, Katerina Izmailova, because her dramatic variousness was peerless last night. Sarcasm, voluptuousness, ghostly pathos – the setting of Apollinaire’s “The Suicide”, with its haunting ‘Three lilies” refrain – hysteria and hallowed depths (in Rilke’s “The Death of the Poet”): all were on parade, but meshed with the stupendous playing of the small string ensemble Shostakovich asks for and the startling percussion interjections. Occasionally the words are lost in the sheer enveloping warmth of tone, but in the big outbursts Stikhina could not have been more vivid.  Vitalij Kowaljow (pictured above with Stikhina, Noseda and the LSO) is the true bass needed for the symphony’s heart of darkness, equally terrifying at full pelt, though perhaps a little more warmth would have better matched the weeping cello ensemble, superbly led by David Cohen in the Küchelbecker ode to his departed fellow-poet Delvig, the one moment where a touch of sentimentality, in the positive sense, is allowed to enter Shostakovich’s grim canvas. What a masterpiece this is, though, down to the extraordinary writing the composer gives the two double basses (Lorraine Campet and Patrick Laurence, utterly compelling). It would, incidentally, help the understanding if the translations could be given in supertitling; no-one wants to have head buried in programme when the drama needs watching.

Vitalij Kowaljow (pictured above with Stikhina, Noseda and the LSO) is the true bass needed for the symphony’s heart of darkness, equally terrifying at full pelt, though perhaps a little more warmth would have better matched the weeping cello ensemble, superbly led by David Cohen in the Küchelbecker ode to his departed fellow-poet Delvig, the one moment where a touch of sentimentality, in the positive sense, is allowed to enter Shostakovich’s grim canvas. What a masterpiece this is, though, down to the extraordinary writing the composer gives the two double basses (Lorraine Campet and Patrick Laurence, utterly compelling). It would, incidentally, help the understanding if the translations could be given in supertitling; no-one wants to have head buried in programme when the drama needs watching.

Somehow there was something exultant about the experience, a human victory in mastering the darkest sentiments, rather than the bleak despair you might expect to experience. So the move to the A major light of Beethoven’s Seventh wasn’t such an extreme jolt. The spring in the heel which is one of Noseda’s most engaging characteristics was even there as oboist Olivier Stankiewicz – visibly enjoying every minute made his opening summons, and with textures crystal-clear, the wind capped by Gareth Davis’s blissfully singing flute could always be heard even above the now-large string section. The interpretation uniquely reminded us, too, that Beethoven's quieter moments, so intense here, can be so meaningful in a work which tends to be remembered for its exhiilarating high volume; the crescendos, too, were masterly. The fast pace at which Noseda took the scherzo and finale especially would seem to cry out for a smaller number of players, but maximum articulation was miraculously achieved by the LSO’s glorious strings. Curiously, the last chamber version I heard, with Maxim Emelyanychev conducting the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, felt rushed and even garbled, while here Noseda reminded us that the music is always to be danced. No wonder many of the young people in the audience shot to their feet at the end; there’s no better introduction to orchestral not-too-heavy metal than this. And yes, those final torrents always set the pulses racing. But this was a performance in a thousand, no doubt about it.

The fast pace at which Noseda took the scherzo and finale especially would seem to cry out for a smaller number of players, but maximum articulation was miraculously achieved by the LSO’s glorious strings. Curiously, the last chamber version I heard, with Maxim Emelyanychev conducting the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, felt rushed and even garbled, while here Noseda reminded us that the music is always to be danced. No wonder many of the young people in the audience shot to their feet at the end; there’s no better introduction to orchestral not-too-heavy metal than this. And yes, those final torrents always set the pulses racing. But this was a performance in a thousand, no doubt about it.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Hallé John Adams festival, Bridgewater Hall / RNCM, Manchester review - standing ovations for today's music

From 1980 to 2025 with the West Coast’s pied piper and his eager following

Hallé John Adams festival, Bridgewater Hall / RNCM, Manchester review - standing ovations for today's music

From 1980 to 2025 with the West Coast’s pied piper and his eager following

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James's Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James's Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Comments

I so agree about the need for